A new era in cancer treatment?

- Published

- comments

Cancer patient Vicky Brown tells the BBC's Fergus Walsh the drugs therapy gave her two more years with her granddaughter

When it comes to reporting medical science, "breakthrough" is a very overused word, and one I usually try to avoid.

When dealing with cancer, I also prefer not to talk about cure - it's a hostage to fortune, given that the disease can lie dormant for long periods only to emerge many years later.

Headline writers like both terms - they form a neat shorthand to advertise many stories of medical advance.

"Breakthrough" does seem justified, whereas "cure" does not, when referring to a slew of results from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) concerning a new generation of cancer treatments.

The main excitement from ASCO was prompted by a form of treatment known as immunotherapy - using drugs which unmask the ability of cancer to switch off the immune system and so hide from the body's natural killer cells.

In a key trial, nearly six in ten patients with advanced melanoma saw their disease halted for almost a year when treated with a combination of ipilimumab and a new immunotherapy drug, nivolumab.

Until recently survival time for patients with melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer, was just a few months.

For the BBC's Panorama, I followed one patient, Vicky Brown, 61, from Cardiff, who was part of the major trial led by London's Royal Marsden Hospital and Institute of Cancer Research.

Her melanoma had spread to her breast, lungs and neck and she initially thought she had months to live.

Instead the combination therapy shrank her tumours and left her apparently disease-free for two years.

'Game-changing'

Although there were severe but temporary side-effects on her liver, Vicky says the treatment gave her her life back.

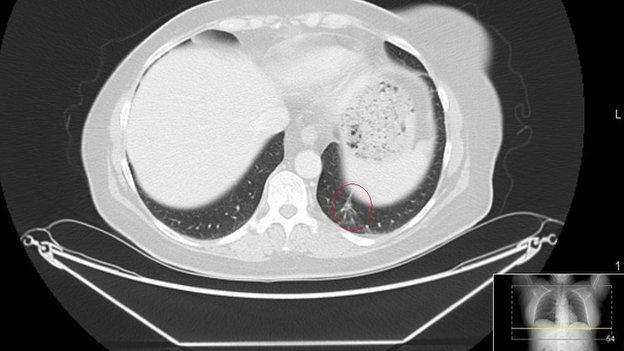

Vicky has recently been diagnosed with another tumour in her lung, so will need follow-up treatment.

That is why it is premature to talk about curing advanced cancer, which has spread through the body.

Nonetheless, given the grim outlook that used to exist for advanced melanoma, it's easy to see why cancer specialists have been using terms such as "game-changing" and "paradigm shift".

Not least because immunotherapy treatments are also showing promise with several other forms of cancer.

But these new drugs come at a price.

They cost hundreds of millions of pounds to develop - many treatments that go through trials end up in costly failure.

So the drug companies want to make a return on investment - and a profit for shareholders - while the drugs are still on patent, before cheaper generic versions are available.

Ipilimumab, one of the combination immunotherapy drugs in the trial, costs around £75,000 per patient.

The other drug in the melanoma trial, nivolumab, is not yet licensed in Europe. It has also been shown to extend life expectancy in lung cancer - the biggest of all cancer killers.

It is licensed in Japan at a reported cost of nearly £100,000 a patient, although once approved in the UK there would be a confidential NHS agreed price, as with other new drugs.

Genetic switches

Several pharma companies have immunotherapy drugs undergoing trials, with promising results against melanoma, lung, liver, bowel, head and neck cancers.

There is also plenty of excitement about a new range of cancer drugs which target genetic weaknesses in tumours.

These are the result of our far greater understanding of the biology of cancer, and the genetic switches which drive the disease.

Increasingly doctors will classify cancer, not by the organ of origin, but by its genetic make-up.

Some men with prostate cancer have been shown to benefit from a drug originally intended for women with inherited genetic defects leading to breast and ovarian cancer.

The drug, olaparib, was recently licensed for ovarian cancer, but has just been rejected by the drug watchdog NICE, on grounds - at £4,000 a month - of cost.

The regulator said it had not yet shown it extended life expectancy beyond existing drugs.

Such data may take years to emerge. The trials do show that the drug is often better tolerated, with fewer side-effects, than conventional chemotherapy.

The decision has dismayed British cancer researchers, who spent 20 years developing the drug and say around 450 women a year will be denied access.

Expect many more difficult decisions on cancer drugs. There are potentially dozens of new treatments coming through in the next few years.

With a finite health budget and competing demands from dementia, stroke, heart disease, diabetes and more, the NHS will have to make some challenging decisions on what price it puts on extending the lives of cancer patients.

Panorama: Can You Cure My Cancer? is still available on the BBC iPlayer

- Published1 June 2015

- Published11 February 2015