Down's blood test 'would cut risk of miscarriage'

- Published

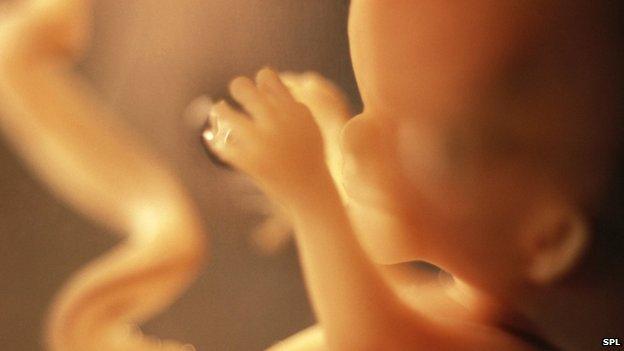

The current test for high-risk pregnancies, an amniocentesis, increases the likelihood of miscarriage

A safer test for Down's syndrome that reduces the risk of miscarriage could soon be available on the NHS.

One in every 200 women loses her baby after an amniocentesis, in which the fluid around the developing foetus is tested for genetic disorders.

A trial at Great Ormond Street Hospital of the new test - for fragments of foetal DNA in the mother's blood - suggested it could be cost-effective.

The NHS is to decide if it should be added to screening for Down's syndrome., external

About 750 babies are born with Down's syndrome in the UK each year.

All pregnant women are offered testing for genetic disorders.

Initially an ultrasound scan and chemicals in the mother's blood are used to assess the likelihood of the baby having Down's.

Anyone calculated to have up to a one-in-150 chance of a baby with Down's syndrome is offered an amniocentesis - in which a needle is used to extract a sample of amniotic fluid, which surrounds the foetus.

But those women, of whom most would probably not have a baby with Down's, need to decide whether to have the risky test.

Safer blood

Fragments of the developing foetus's DNA naturally end up in the mother's bloodstream.

"Non-invasive prenatal testing" - or NIPT - uses this DNA to test for major genetic abnormalities.

It is already used in nearly 100 countries, but Great Ormond Street Hospital has assessed how it could be used on the NHS.

Prof Lyn Chitty, who led the trial, told the BBC: "It's a much more accurate test, it's 99% accurate for Down's syndrome so it reduces the number of [invasive] tests significantly.

"In our study it reduced the number of invasive tests by more than 80%, whilst actually picking up more cases of Down's syndrome."

However, it does not completely eliminate the need for an amniocentesis.

Anyone who has a positive NIPT test result would still need final confirmation with an amniocentesis.

Dr Lucy Jenkins, head of laboratory services at Great Ormond Street, called the test an important breakthrough.

"We know that there's a small amount of the baby's DNA actually circulating in the mother's bloodstream, so by taking just the blood sample from the mother we can detect the baby's DNA.

"What we're actually looking for is a slightly increased amount of chromosome 21, and it's an extra chromosome 21 that causes Down's syndrome."

Shelley Thoupos describes having an amniocentisis test during pregnancy

One anonymous mother who took part in the trial said: "We probably wouldn't have done [invasive testing] because there's a risk of miscarriage.

"I think that we were very lucky, it's enabled us to make an informed choice about what happens for the rest of our lives."

Shelley Thoupos, whose nine-year-old son Sam has Down's syndrome, said she was concerned people were not well informed and often had a very negative view of it.

She welcomed the new test, saying: "I think anything that isn't invasive and anything that isn't going to have a risk of a miscarriage is good. I think it's good for parents to be prepared and everyone has a right to choose what they are going to do with their own life."

But she added: "I think the problem comes from a lack of education because unfortunately most people do not continue with their pregnancies.

"I think we have to look at us as a whole and the fact we are not educated about Down's syndrome [or]... about how well our children can go on and live their lives."

Ms Thoupos also said that during her pregnancy - after having an amniocentesis test - she had had signs of early labour at 23 weeks, which meant Sam's life was in danger.

The possibility of losing Sam was "devastating", she said.

"To have gone through everything we had gone through, to realising we were having this child, to having decided together 'that's it, we're doing this', and to then think we could lose him over having done this [amniocentesis] test, was devastating."

The new blood test may save the NHS money in the long term

Cost saving

Prof Chitty, who will present data from the trial involving 2,500 mothers at the European Society of Human Genetics conference.

She said that while the blood test is costly, it could help the NHS save money by reducing the number of expensive amniocenteses.

Prof Chitty said the trial showed many women who would have refused an amniocentesis chose to have the safer test to help them prepare.

She also rejected the idea that the extra testing would necessarily lead to more abortions:

"It may offer parents more choices, but I don't think all of those parents are necessarily going to choose to terminate the pregnancy.

"In our study, there was a significant number who chose to carry on with the pregnancy with the knowledge that the baby had Down's syndrome and they were grateful for that knowledge."

The UK's National Screening Committee will begin assessing the idea this month.

Dr Anne Mackie, its director of programmes, said: "Before NIPT can be safely introduced we must be sure it is accurate when used on large numbers of women and that there are quality-assessed pathways in place providing the care, support and information women need."

England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland would each make their own decision on whether to make any recommendations.

- Published1 April 2015

- Published1 November 2013

- Published14 July 2014