Why are GPs so angry?

- Published

Next week hundreds of doctors will descend on Liverpool for their annual conference.

The gathering of the British Medical Association is not really a time for celebration. It tends to be more about airing grievances.

But, even given that, there will be one group of medics that are unhappier than the rest. GPs.

Surveys suggest many can't wait to escape. A third of doctors say they are planning to retire in the next five years and even those who are just starting out seem unsure they want to be there with one in five trainees planning to go abroad and many areas in England struggling even to fill the trainee places in the first place.

How have we got into this situation? After all, a decade ago they were handed a new contract which gave them the ability to opt out of the deeply unpopular night and weekend cover and saw their pay shoot up over the £100,000 barrier.

GPs - arguably more so than A&E - are the front door of the health service. Nine in every 10 contacts with the NHS come via them and, as a result, they are bearing the brunt of the growing pressure on the health service.

The number of consultations they do has risen by 13% to 340 million a year in the past four years and you now find GPs claiming they have to work 12 or even 14-hour days to keep up.

BMA GP leader Dr Chaand Nagpaul talks about it being a "hurricane" of rising patient demand, declining recruitment and a lack of investment that could lead to the end of a general practice as we know it. He has spent the past year demanding action.

'Long hours'

But there seems to be more to it than that. After all, long hours and constant demands from patients have always been part of the GP's lot.

ARCHIVE: An NHS GP in 1965 complains that Britain is "grossly under-doctored"

In many ways, they may have found themselves to be a victim of that contract the BMA so skilfully negotiated all those years ago. It has created the perception that the profession had a good deal and so with money scarce other parts of the NHS have arguably been given more attention.

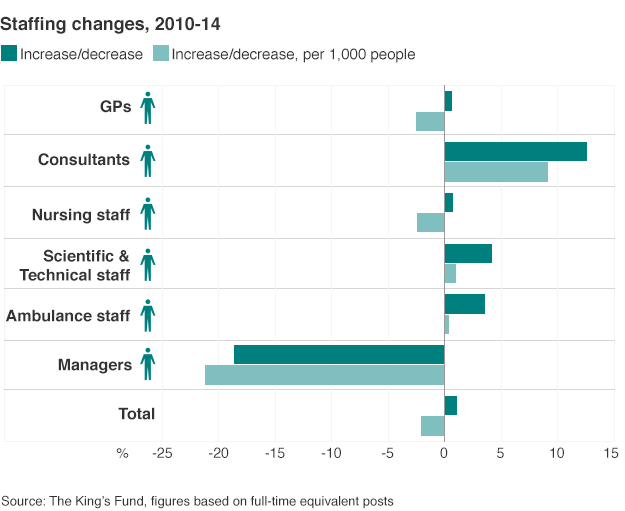

While overall numbers have increased slightly, when it comes to numbers per head of population there has actually been a fall. By comparison, consultant numbers are up - as the graph below illustrates.

Only managers have fared worse - and there has been a specific push to reduce their numbers.

To be fair, ministers have already recognised investment is needed with the Tories promising an extra 5,000 GPs during this parliament.

But it is not a something for nothing deal. Twinned with this will be a push to move towards seven-day services. Sara Khan, a GP from Hertfordshire, is just one of many GPs that have been openly critical about the policy. Her practice has already experimented with extended opening and found patients were not particularly interested.

"Rather than spreading ourselves thinly we need to focus on the core service that is needed," she says.

Nonetheless, the government is determined to push on - and that in turn is changing the nature of general practice. Gone are the days when large numbers of GPs worked alone in single-handed practices.

Instead GPs are increasingly becoming employees of large practices rather than their own bosses as the traditional GP partner model allows. With that, there is a sense among GPs that the profession is beginning to lose its identity.

The rise of the 'super-surgery'

GPs have traditionally seen themselves as the entrepreneurs of the NHS. Since the NHS was created they have operated effectively as self-employed professionals in charge of running their own practices.

But that is changing. Today only two-thirds in England are GP partners as there has been a trend towards become a salaried GP, employed by the practice they work for.

It means the number of one-doctor practices has halved over the last seven years and there are now fewer than 1,000 in England out of a total of more than 30,000. In their place has emerged the "super-surgery" of 10 doctors or more. There are more than 500 of these.

What is more, there is also a trend towards practices working in partnerships with others, effectively becoming franchises. It allows for a wider range of care to be provided - something that many believe is essential to meet the needs of an ageing population.

This was something recognised by the Nuffield Trust last year. Mark Dayan, who led the research that was published in November, said at the time working in "bigger, better organised groups" would be key to the survival of general practice.

But he warned the government would need to be supportive to GPs to allow them to adapt. Perhaps the key question is not why GPs are so angry but whether ministers - under pressure to fulfil their ambitions for the NHS - have the patience to work with the profession.

- Published4 June 2015

- Published13 June 2014

- Published5 March 2015