Sugar: Can we trust industry?

- Published

- comments

Imagine a kilo of sugar - the large bag that you might buy in a supermarket.

It's a lot, isn't it? But that's exactly how much sugar the average adult consumes in a fortnight. Teenagers have even more.

This is the reason why the sweet stuff is the new frontier in the campaign to get people to live healthier lives.

One of the problems is that it's often hidden in the foods we eat. While fizzy drinks and confectionery are obvious sources, you may be surprised to learn that tinned soups, salad dressing and tomato ketchup all contain pretty high levels of sugar.

Government advisers have recently suggested no more than 5% of daily calories should come from added sugar - half the level of the previous recommendation.

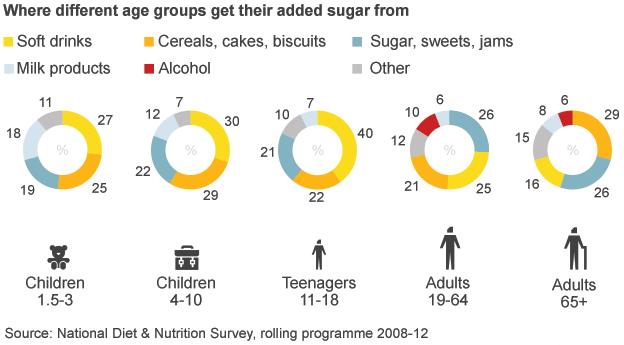

But that is going to be a tough ask. No age group was meeting the old guideline, never mind getting close to the new one.

The response of health campaigners has been to call for tougher regulation - and in particular a tax on sugary drinks.

This is understandable. A typical can of pop can contain the equivalent of 9 teaspoons of sugar.

But the government does not seem to want to regulate, preferring to work in partnership with industry and pointing out many manufacturers and retailers have already started taking action.

Just this week Tesco announced it would stop selling high-sugar drinks specifically aimed at children, including certain types of Ribena and Capri-Sun.

While the move was widely welcomed, is it really wise to leave it to industry to help improve the health of the nation?

Of course the sector says yes. It points to the introduction of low-calorie and zero-calorie drinks - now accounting for half of all sales of fizzy drinks - and that the growth in bottled water is one of the fastest-growing areas of the drinks business.

The sugar problem

There has been growing concern about the damaging impact of sugar on health - from the state of people's teeth to type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Sugar has been dubbed "empty calories" because it has no nutritional benefit.

Government advisers recommend that no more than 5% of daily calories should come from sugar.

That's about 25g (around six or seven teaspoons) for an adult of normal weight every day. For children it is slightly less.

The limits apply to all sugars added to food, as well as sugar naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices and fruit concentrates.

To put this in context, a typical can of fizzy drink contains about nine teaspoons of sugar.

But the fact still remains that the number of fizzy drinks being consumed is still rising. Last year the average Briton drank 100 litres - 5% more than was consumed six years ago.

Instead of simply encouraging people to swap their drinks to "healthier alternatives", these new products seem to be actually growing the market.

However, Barbara Gallani, from the Food and Drink Federation, says the industry has also shown it is committed to making existing products healthier where it can, pointing to its track record on salt.

"Many companies have been voluntarily lowering salt in products for over a decade and this has contributed to an impressive 15% reduction in salt intake."

Consumer choice

This is based on figures from 2003 to 2011, which show salt consumption fell from 9.5g to 8.1g per day. The record is pretty good, certainly better than many other countries have achieved.

And it is worth noting that the salt content of products on sale in supermarkets has actually reduced by much more - between 20% and 40%, according to industry estimates.

The problem is that many shoppers still gravitate towards options with more salt.

Ms Gallani says educating and influencing consumer demand has to be at the heart of any drive to reduce sugar intake. "Often there are only so many changes to a favourite food or drink a consumer will accept," she adds.

But many campaigners believe industry is just trying to put up barriers to slow progress.

"Yes, of course, we have to get the public health message out," says Dr Gail Rees, an expert in nutrition at Plymouth University. "But you have to consider what we can spend compared to what the industry can put into marketing its products.

"A sugar tax is just one of the things we should be looking at. We need to think about greater restrictions on advertising and the way products are promoted."

Within retailing this is known as the four Ps - product, price, promotion and place. For example, the way packages are designed, where they are placed in store or which celebrity is endorsing them can have just as significant an impact on consumers as how much they cost.

For sugary drinks and sweets this is even more important. Research shows the overwhelming majority of confectionery purchases are impulse buys: bought because they caught your eye as you passed.

If sugar is the new frontier in the fight against obesity, it promises to be a long and hard battle.