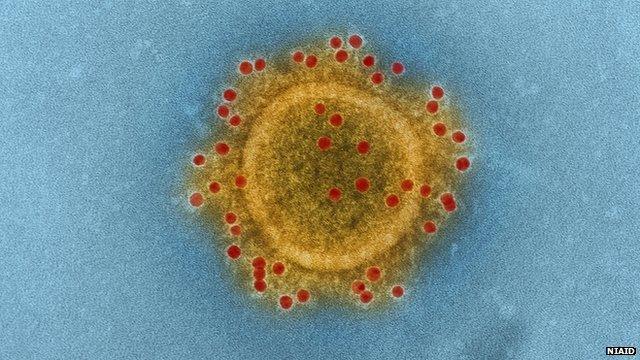

Vaccine for Mers coronavirus 'looks promising'

- Published

A prototype vaccine against the lung infection Mers coronavirus has shown promising results, scientists say.

The study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, suggests the vaccine guards against the disease in monkeys and camels.

Researchers hope with more work it could be turned into a jab for humans.

Mers has infected 1,400 people and claimed 500 lives since 2012. But no specific treatment or preventative medicines exist.

In the majority of cases, individuals are thought to have caught Mers (Middle-East respiratory syndrome) through close contact with infected patients in hospital.

Two-prong approach

But experts suspect camels also play an important role - acting as a host for the disease.

The researchers, led by University of Pennsylvania, say their experimental vaccine could be a "valuable tool" in two different ways - first, to immunise camels to stop it spreading to human populations and, secondly, as a jab to protect individuals at risk of getting Mers.

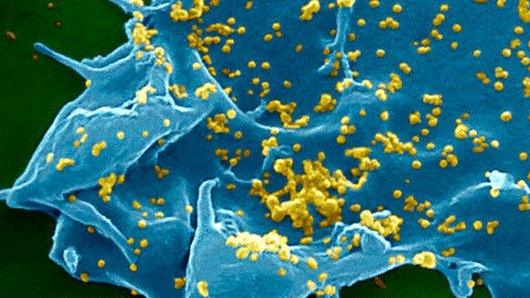

In the trial, the vaccine was tested on blood samples taken from camels and appeared to kick-start the production of antibody proteins that may help mount a defence against the virus.

And when it was given to macaque monkeys later exposed to Mers, the animals did not become ill.

Prof Andrew Easton, from Warwick University, described the research as a "significant step forward in the generation of a vaccine to prevent Mers disease".

He added: "The data show that the vaccine is capable of generating protective antibodies in laboratory studies and also in camels.

"This is very promising as a possible way to reduce virus spread in camels and therefore to reduce the risk of infection in humans."

Other experts caution that since the virus tends to affect macaques less severely than humans, it is not yet clear whether it could definitely be used as a vaccine in human populations.

The research was funded in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the US and Inovio Pharmaceuticals.

- Published10 June 2015

- Published2 July 2015

- Published15 June 2015