Assisted Dying Bill: MPs reject 'right to die' law

- Published

- comments

People for and against the assisted dying bill campaigned outside Parliament

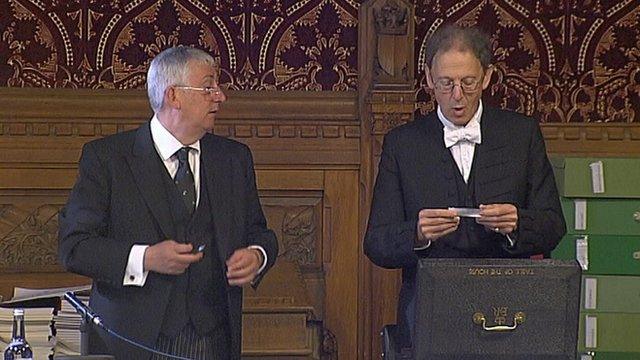

MPs have rejected plans for a right to die in England and Wales in their first vote on the issue in almost 20 years.

In a free vote in the Commons, 118 MPs were in favour and 330 against plans to allow some terminally ill adults to end their lives with medical supervision.

In a passionate debate, some argued the plans allowed a "dignified and peaceful death" while others said they were "totally unacceptable".

Pro-assisted dying campaigners said the result showed MPs were out of touch.

Under the proposals, external, people with fewer than six months to live could have been prescribed a lethal dose of drugs, which they had to be able to take themselves. Two doctors and a High Court judge would have needed to approve each case.

Dr Peter Saunders, campaign director of Care Not Killing, welcomed the rejection of the legislation, saying the current law existed to protect those who were sick, elderly, depressed or disabled.

He said: "It protects those who have no voice against exploitation and coercion, it acts as a powerful deterrent to would-be abusers and does not need changing."

But Sarah Wootton, the chief executive of Dignity in Dying, said it was an "outrage" that MPs had gone against the views of the majority of the public who supported the bill.

She added that "dying people deserve better".

Analysis

By James Gallagher, health editor BBC News website

A series of high profile and emotionally charged right-to-die cases have appeared in the courts.

But the response from judges has been clear. As Lord Justice Toulson ruled in the case of Tony Nicklinson: "These are matters for Parliament to decide."

Now the message from politicians has been an overwhelming rejection of the right to die.

And opinion is not shifting - 74% of MPs voted against this bill compared with 72% back in 1997.

The emphatic nature of the result would suggest politicians are unlikely to discuss this again soon.

Campaigners will regroup and point to their own polls showing 82% of the public back assisted dying and calls for change may yet intensify with an ageing population.

One thing is certain - the intense pressure on the courts and politicians is not going away.

Impassioned debate

Rob Marris, Caroline Spelman, Crispin Blunt, Lyn Brown, Keir Starmer, Nadine Dorries and Dr Liam Fox speak for and against the Assisted Dying Bill

The latest proposals were brought before the Commons by Rob Marris, the Labour MP for Wolverhampton South West.

Opening the debate, Mr Marris said the current law did not meet the needs of the terminally ill, families or the medical profession.

He said there were too many "amateur suicides, and people going to Dignitas" and it was time for Parliament to debate the issue because "social attitudes have changed".

Mr Marris added: "This bill would provide more protection for the living and more choice for the dying."

Mr Marris said he did not know what choice he would make if he was terminally ill, but said it would be comforting to know that the choice was available.

Fiona Bruce, the MP for Congleton, said the bill was so completely lacking safeguards for the vulnerable that "if this weren't so serious it would be laughable".

Her impassioned speech concluded: "We are here to protect the most vulnerable in our society, not to legislate to kill them. This bill is not merely flawed, it is legally and ethically totally unacceptable."

The law on assisted dying around the UK

Euthanasia, which is considered as manslaughter or murder, is illegal under English law.

The Suicide Act 1961 makes it an offence to encourage or assist a suicide or a suicide attempt in England and Wales. Anyone doing so could face up to 14 years in prison.

The law is almost identical in Northern Ireland.

There is no specific law on assisted suicide in Scotland, creating some uncertainty, although in theory someone could be prosecuted under homicide legislation.

Conservative MP Caroline Spelman added that "the right to die can so easily become the duty to die" and she said the law already provided protection for the elderly and disabled.

She was one of many MPs to argue that it was difficult to determine whether someone had six months or under to live.

She also warned: "[The bill] changes the relationship between the doctor and their patient, it would not just legitimise suicide, but promote the participation of others in it."

Jeffrey Spector's wife, Elaine, and daughter Keleigh explain why he wanted to end his life legally

In a lengthy speech, Labour MP Sir Keir Starmer told MPs about prosecution guidelines he developed in his role as director of public prosecutions, when he had to deal with a number of "right to die" cases, including those of Debbie Purdy, external and Tony Nicklinson.

But he warned that his guidelines had shortcomings without a change in the law.

He said: "We have arrived at a position where compassionate amateur assistance from nearest and dearest is accepted, but professional medical assistance is not unless you have the means of physical assistance to get to Dignitas.

"That, to my mind, is an injustice we have trapped within our current arrangements."

Michael Wenham, who suffers from motor neurone disease, believes some disabled people could feel pressure to relieve carers of the "burden" of looking after them

An emotional Dr Philippa Whitford, the SNP's health spokeswoman and a breast cancer surgeon, argued that with good palliative care, the "journey can lead to a beautiful death".

"We should support letting people live every day of their lives till the end," she said, and she urged MPs to vote for "life and dignity, not death".

Justice Minister Mike Penning closed the debate, saying he opposed the bill for two reasons - firstly because he didn't think it should be an excuse that "we can't control pain in the 21st Century".

He also said he was against suicide because he had seen the painful aftermath of far too many.

Where others stand on assisted dying

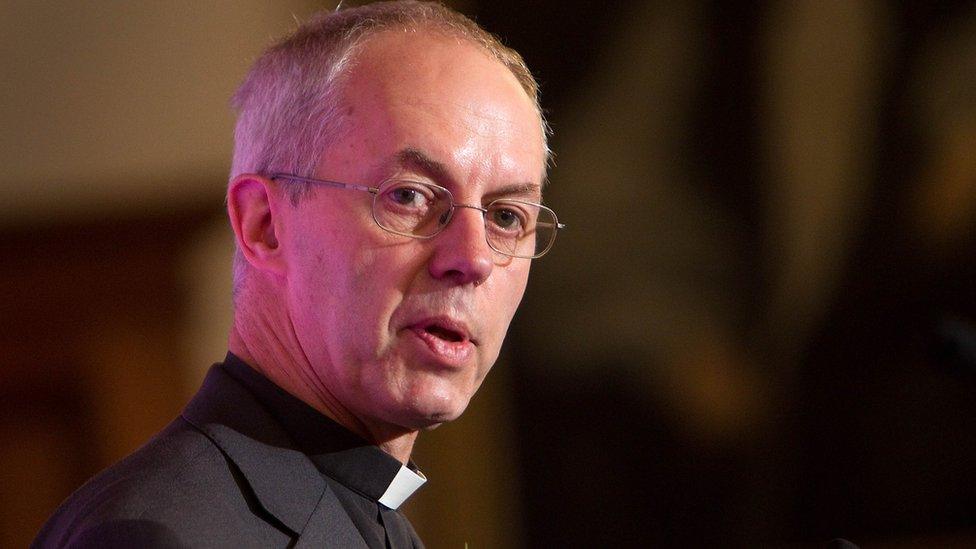

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, said the bill would mean suicide was "actively supported" instead of being viewed as a tragedy

One of his predecessors, George Carey, backs assisted dying saying that there's nothing dignified about experiencing pain at its most awful

The British Medical Association, the doctor's union, opposes all forms of assisted dying

The Royal College of Nursing takes a neutral stance

- Published10 September 2015

- Published11 September 2015

- Published26 May 2015

- Published6 September 2015

- Published17 July 2014

- Published12 June 2014

- Published27 May 2015