Miniature human kidney grown in a dish

- Published

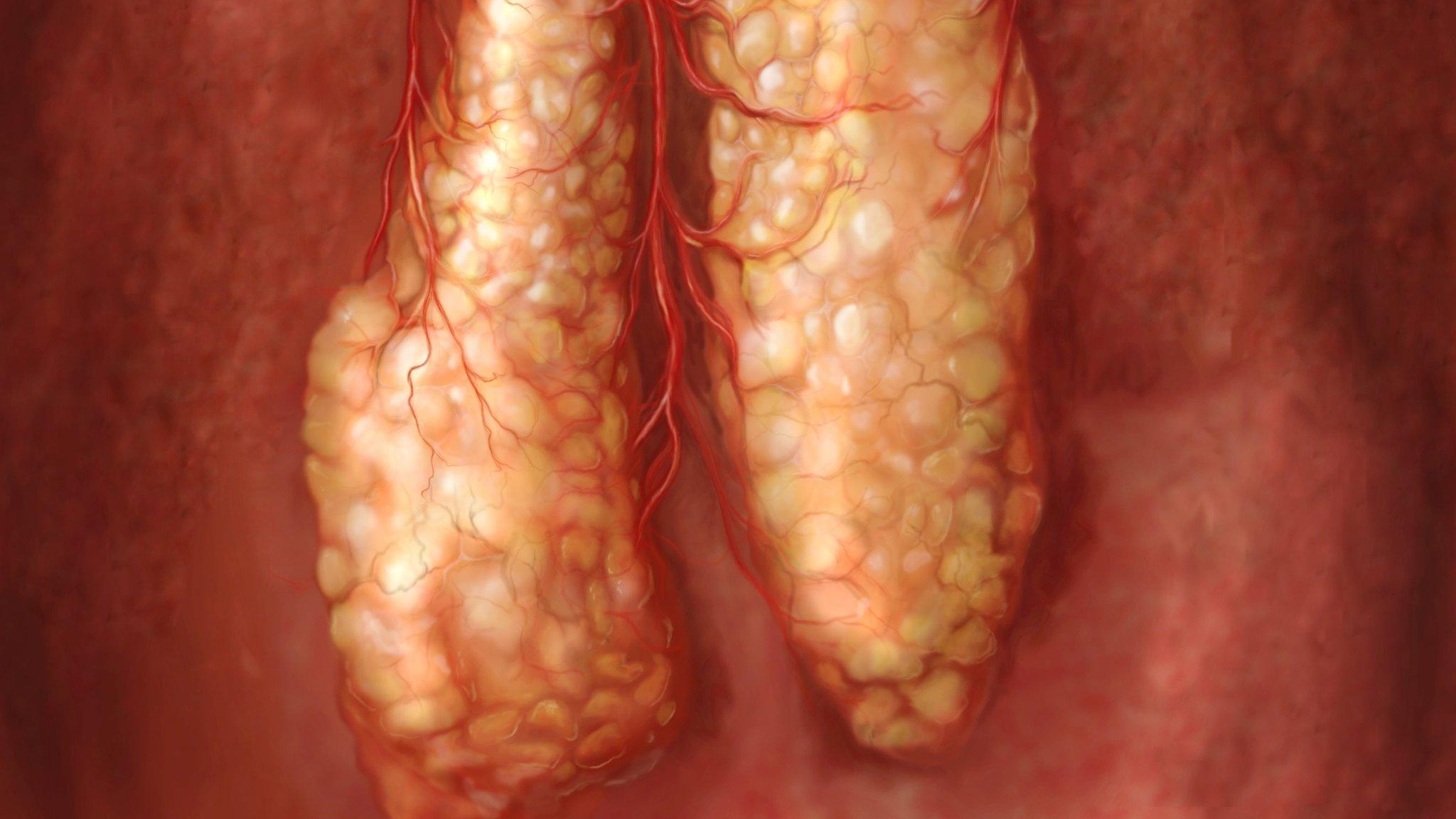

The kidney "organoid" growing in a dish

Miniature human kidneys have been grown in a Petri dish using stem cells as the starting point, report scientists in Australia.

The mini-kidneys, measuring up to 1cm, were the equivalent of the developing organ in a 13-week-old foetus.

The team say the findings, published in the journal Nature, external, could lead to new ways of testing drugs and eventually a way of replacing damaged kidneys.

Experts said there was still a long way to go.

The scientists were mimicking the process that takes place inside the womb when a single fertilised egg produces the whole array of precisely arranged tissues of the human body.

However, their starting point was human skin cells that had been chemically transformed into a type of cell capable of becoming any other - a stem cell.

Signals

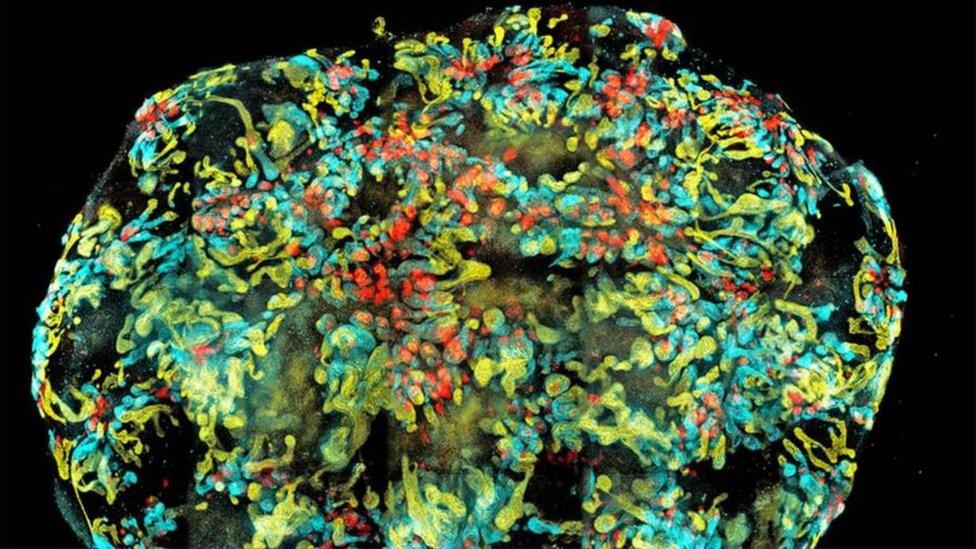

The team used chemical signals to transform the stem cells into two types of cell.

One goes on to produce the structures that filter the blood and the other the collecting ducts that remove the waste.

When the two cell-types were brought together in a dish they grew and arranged themselves into the complex structure of a kidney.

The mini-kidneys are so small they cannot be termed organs. The "organoids" contained between 50 and 100 filters while an adult kidney has more than a million.

The researchers aim to replace fully-grown kidneys

Prof Melissa Little, one of the researchers from the Murdoch Children's Research Institute, told the BBC News website: "We've been able to show we can take human stem cells and in a dish make a structure like a small developing kidney.

"The aim in the very long-term is to see if we can recreate an organ that would be good enough to treat someone with kidney disease."

However, as the growing organoids do not have a blood supply there is still a long way to go before full-size organs can be grown in the lab.

"This is what we can get to in three weeks, but there is a limit to what you can grow in a dish without nutrients and oxygen," Prof Little added.

'Major step'

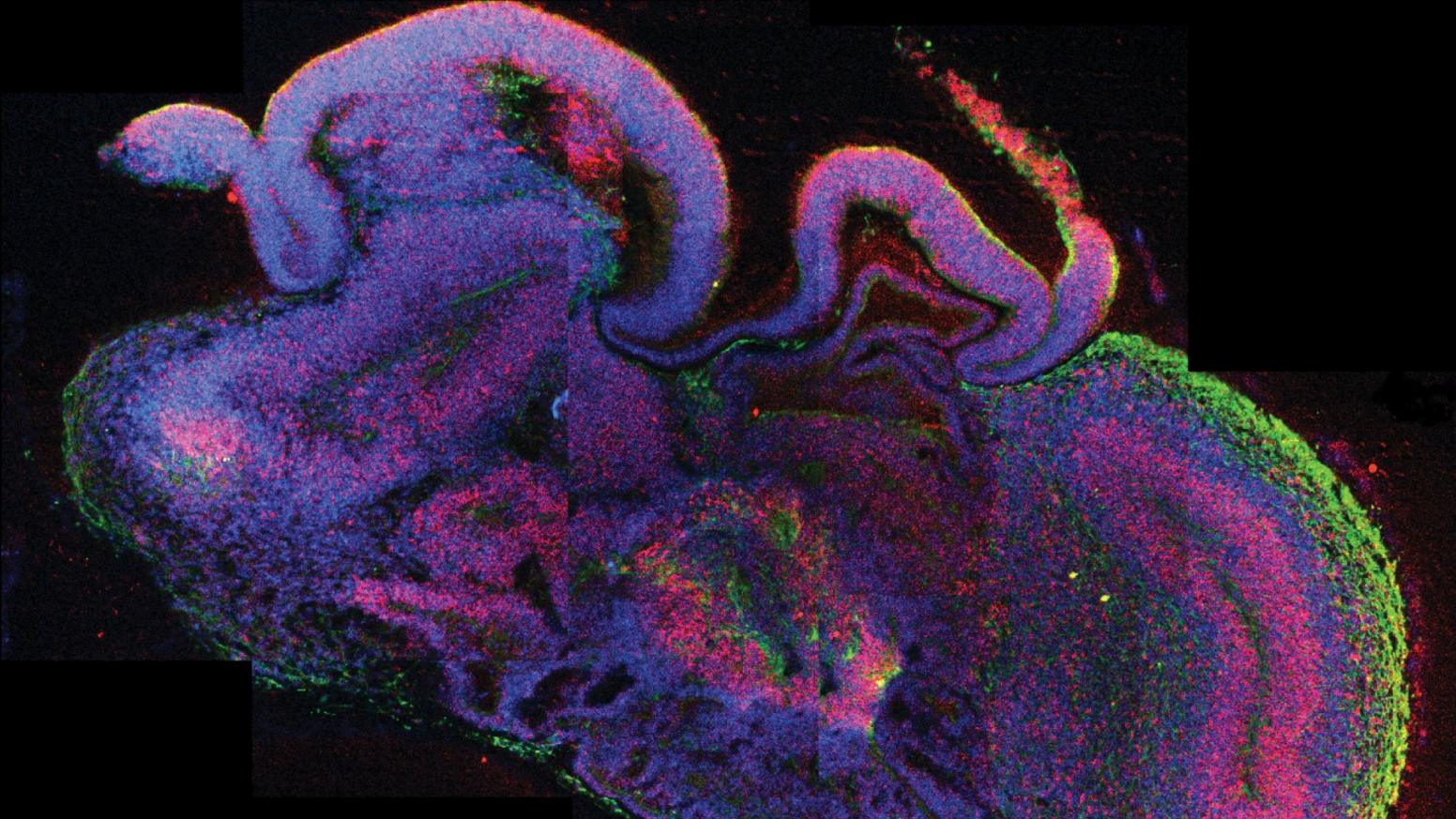

It marks the latest development in a process of growing organoids which has already seen the development of mini-brains and livers.

Prof Jamie Davies, from the University of Edinburgh, commented: "It is vital to emphasise that the result of this process is not a kidney, but an organoid - it lacks large-scale features that are crucial for kidney function.

"There is a long way to go until clinically useful transplantable kidneys can be engineered, but [the study] is a valuable step in the right direction."

However, he said the organoids could be used to test the toxicity of new drugs and could mark a "major step" towards replacing animals in such experiments.

Follow James on Twitter, external.

- Published30 October 2010

- Published28 August 2013

- Published24 August 2014