Are three-quarters of English hospitals really unsafe?

- Published

The majority of hospitals in England are not really unsafe - of course not. That would be a staggering situation to find in the 21st century NHS.

But the way the Care Quality Commission has presented its evidence has allowed that idea to form.

Its State of Care report, external - essentially its annual report of what it has been up to over the last year - contains information showing 74% of the hospital trusts it has assessed since April under its new inspection regime have safety problems.

However, the issue with this is that the trusts in question are not really representative of the entire NHS.

The figure relates to inspections of only 79 hospital trusts - that is less than half the total in existence.

What is more, many of those trusts have been targeted because of existing concerns about them - the CQC has used evidence that is already available, such as death rates and staff surveys, to predominantly focus on those where there are known risks.

Therefore, as this inspection regime continues you would expect a rosier picture to emerge.

The other problem is how the CQC defines safe. Hospitals can find themselves falling foul of inspectors because of - some argue - relatively innocuous oversights. For example, they can be rapped over the knuckles if they fall behind on training or record keeping.

'Strong indication'

This is not to say that such issues need not be tackled. It's just that this is a very long way from what many people's definition of safe is.

Equally, there was plenty of evidence put forward that is extremely worrying, including warnings that wards are under-staffed and patients left without being properly assessed and cared for.

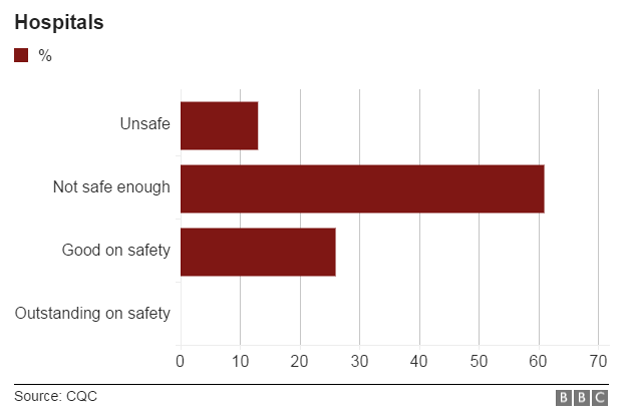

It means the CQC actually broke the 74% figure down into 13% of trusts where there was a "strong indication that care was unsafe" and 61% where safety could be improved.

Another factor to consider is the pressure the CQC is under. It was formed in 2009 but quickly found itself facing criticism for being too soft in its inspections - at the time it was struggling to recruit inspectors and had a huge workload because it was running a new system which meant it had to register thousands of care agencies and GPs as well as hospitals.

It was then hauled over the coals for its handling of Furness General Hospital - it gave the hospital that was subsequently found to have covered up the deaths of babies at its maternity unit a clean bill of health in 2010.

The CQC's chief executive and chair left in 2012 and a new leadership team was brought in. They have overseen the introduction of a new "tougher" inspection regime, which started last year and has formed the basis of this report.

But a common complaint on the wards of hospitals is that inspectors are over-reacting and are too ready to damn hospitals.

The result, unfortunately, is a very muddy picture in which it is extremely difficult to come to firm conclusions.

- Published16 July 2015

- Published16 July 2015

- Published21 June 2015

- Published19 June 2015

- Published19 June 2015

- Published30 September 2014

- Published15 December 2013