Sugar tax: Is the government caught in a trap?

- Published

- comments

The review on sugar by Public Health England is clear: a tax on fizzy drinks is not the silver bullet.

In fact, it argues other steps such as tackling price discounting are likely to be more effective at reducing consumption.

But it still does endorse it - and that puts the government in a very tricky position.

To date, ministers have been pretty adamant they don't want to introduce a tax. Even as the report was finally being unveiled, the prime minister's official spokesman was maintaining a tax wasn't on the cards.

But - like it or not - the issue has become a symbolic. Symbolic in the fight against obesity and symbolic of the government's willingness to stand up to industry when it comes to health.

Placing extra levies on something considered to be unhealthy - just as happened with cigarettes all those years ago - is a clear statement that the product is no longer considered an acceptable lifestyle choice. This is why campaigners are so adamant they want to see it.

Sustained pressure

Fizzy drinks are, of course, not the only products we consume that are high in sugar. But it is our attitude to them that is particularly concerning to experts.

While a chocolate bar or slice of cake is generally considered as a treat, fizzy drinks are not. People who drink them, tend to have them every day.

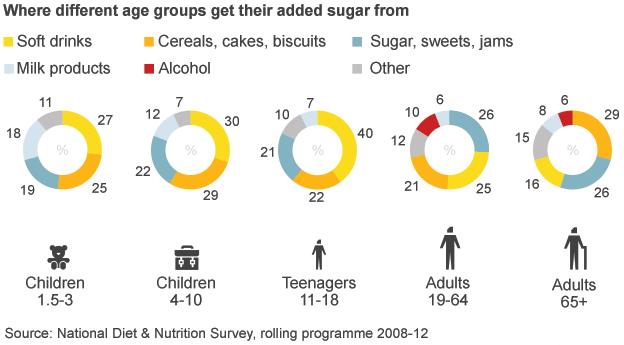

For teenagers they are the number one source of sugar intake. But a typical can contains enough sugar - about nine teaspoons - to take someone over their recommended sugar intake in one hit.

With that in mind, the government is going to come under pretty sustained pressure to change its position on tax ahead of the publication of its child obesity strategy in the new year.

That, of course, is partly because of the way the release of this report has been handled. While it is not unusual for the government to ask experts to review an issue as it draws up new policy, the interest in this review has been on another scale altogether.

The reason for that is simple: when people think something is being kept from them, their interest peaks. This report was handed to ministers in the summer and was due to be released in October alongside the obesity strategy.

But publication of the strategy was delayed and, as a result, so was this report. The House of Commons' Health Committee, which is carrying out its own review of obesity, then started asking why they couldn't see it.

Soon enough media organisations were asking the same questions and then this week it became a front-page story in the newspapers. The government was left with no choice. Now it's out, campaigners will be hoping they can back ministers into a corner again.

- Published22 October 2015