Junior doctors' row: The dispute explained

- Published

Ministers and junior doctors are locked in an increasingly fraught dispute in England. But what exactly is the row about?

What has caused the dispute?

Junior doctors' leaders are objecting to the prospect of a new contract in England.

The government has described the current arrangements as "outdated" and "unfair", pointing out they were introduced in the 1990s.

Ministers drew up plans to change the contract in 2012, but talks broke down in 2014.

They restarted at the end of last year at the conciliation service Acas but a deal could not be reached and so ministers announced in February they would be imposing the contract from this summer.

There are two legal challenges to that imposition which are now being planned, one by the British Medical Association and another by campaign group Just Health.

The one by the BMA focuses on the equalities impact and whether the government paid due regard to it. The government's assessment, when it was published, found aspects of the new contract would impact disproportionately on women.

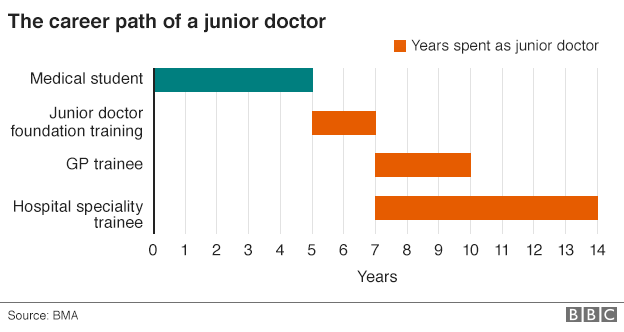

So does this just involve new doctors?

No. The term junior doctor is a little misleading. It covers medics who have just graduated from medical school through to those who have more than a decade of experience on the front line.

The starting salary for a junior doctor is currently just under £23,000 a year, but with extra payments for things such as unsociable hours, this can quite easily top £30,000.

Junior doctors at the top end of the scale can earn in excess of £70,000. But it's important to remember these doctors can be in charge of teams, making life-and-death decisions and carrying out surgery. They are really only behind consultants in seniority.

In total, there are 55,000 junior doctors in England - representing a third of the medical workforce. The BMA has just over 37,700 members.

How is the contract changing?

Basic pay is to be increased by 13.5% on average.

But that comes at a price: other elements of the pay package are to be curbed, including what constitutes unsociable hours.

Day hours on a Saturday will be paid at a normal rate, while extra premiums that are being offered for night and the rest of the weekend are lower than what is currently paid.

Guaranteed pay increases linked to time in the job are also to be scrapped and replaced with a system linked to progression through set training stages.

The current rates for junior doctors and how the government position compares with the BMA's

Will doctors lose pay?

To start with, no. Ministers have promised to protect the pay of existing doctors for the first three years.

A small number - about 1% - who do lots of extra hours and qualify for premium payments that are being scrapped could lose out however.

But these changes are not just about winners and losers on day one. They have partly been designed to make it cheaper to roster extra doctors on at weekends.

Therefore, medics are likely to find they are working more weekends, which, under the existing contract, would have led to extra pay.

What is more, some of the changes will take time to have an effect. For example, the ending of guaranteed pay rises linked to time-in-the-job will mean some doctors find their pay will go up more slowly during their time as a junior medic.

And, of course, new doctors starting their career in the NHS under this contract may be worse off than they would have been if they started under the current deal.

Is there a wider context to this?

Yes. You may have noticed the government in England is intent on improving the range of services that are available seven days a week.

It has also found itself at loggerheads with the BMA over plans to change the consultants' contract - talks are under way on that.

Junior doctors already work weekends - in fact, they provide the bulk of the medical staffing on Saturdays and Sundays.

But the financial benefit of extending what constitutes "normal hours" to a Saturday is obvious.

Is that because death rates are higher at weekends?

This has been one of the most contentious areas of the dispute.

The health secretary has argued that he wants to improve care on Saturdays and Sundays because research shows patients are more likely to die if they are admitted on a weekend.

A study published by the British Medical Journal in September found those admitted on Saturdays had a 10% higher risk of death and on Sundays 15% higher compared with Wednesdays.

But doctors have objected to suggestions that all those deaths are avoidable and could be prevented through increased staffing.

Patients admitted at weekends tend to be sicker and while researchers tried to take this into account they could not say whether they had accounted for it totally.

However, the paper did say the findings raised "challenging questions" about the way services were organised at weekends, while many believe it is access to senior doctors - consultants - that is key rather than junior doctors.

What about the rest of the UK?

The dispute over the contract is an England-only issue.

Scotland and Wales have both said they will be sticking to their existing contracts, while Northern Ireland has yet to make a decision.

This is largely because they do not have the pressures on costs in terms of seven-day services.

While there are moves to improve access to care at weekends elsewhere in the UK, the plans are not on the scale of what the government in England is trying to achieve.

For example, in Wales the focus has been on more weekend access to diagnostic tests, pharmacies and therapies rather than creating more seven-day working across the whole system.

- Published22 September 2015