The bionic eye changing a woman's life

- Published

At Oxford's John Radcliffe Hospital, a clinical trial is taking place in which six patients who have had little or no sight for many years are having a cutting-edge "bionic eye" implanted in an attempt to give them some sight, and independence, back.

The first patient in this trial is 49-year-old Rhian Lewis, from Cardiff.

She explains: "I was a toddler when my parents noticed I would not cross a darkened room, even from one light room to another light room, and that I was really scared of the dark. So they took me back and forward to the optician and specialists and then they diagnosed me with retinitis pigmentosa."

This disorder destroys the light sensitive cells in the retina - but how much and how quickly varies from person to person. In Rhian's case, it eventually made her almost completely blind.

"I think I was about four or five. I've never had any vision at night or in dim light and then, as I went through school, I had the glasses and I sat at the front because I couldn't see the board.

"It was progressive and as I went to work in a shop, checking up deliveries, I had to use a magnifier increasingly to check the delivery notes and then I couldn't read the titles of the books properly, so then they put me on to different materials, like art and stationery, because there were different shapes and sizes so I could manage with that - I could do a lot from memory."

Rhian Lewis has had her sight partially restored

Her sight deteriorated and around 16 years ago she lost all vision in her right eye and most of the sight in her left eye.

"In my left eye, I sort of navigate around by light. If it's bright outside I'll sort of aim for the window or if it's dark and the lights are on I'll navigate by the light bulbs, like a moth."

The problem with having no sight, she says, is that you also lose your confidence because you lose your mobility.

"I don't go out and about on my own, ever. Then around the house, the kitchen, you rely on other people to find things for you - it's very frustrating. It's simple things like shopping...clothes shopping, you don't know what you look like. It's been, maybe eight years that I've had any sort of idea of what my children look like. And I've got friends now where I've got no idea what they look like. And I certainly don't know how I've aged."

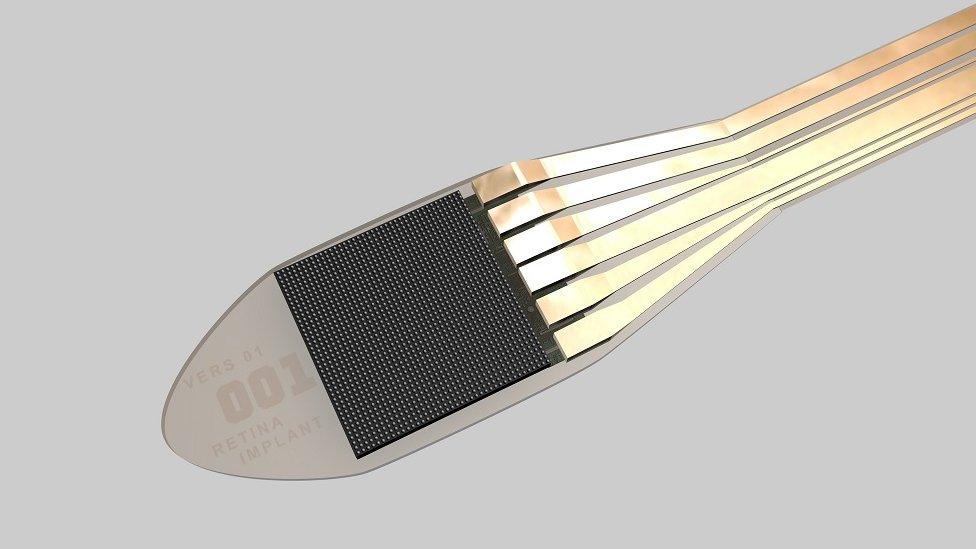

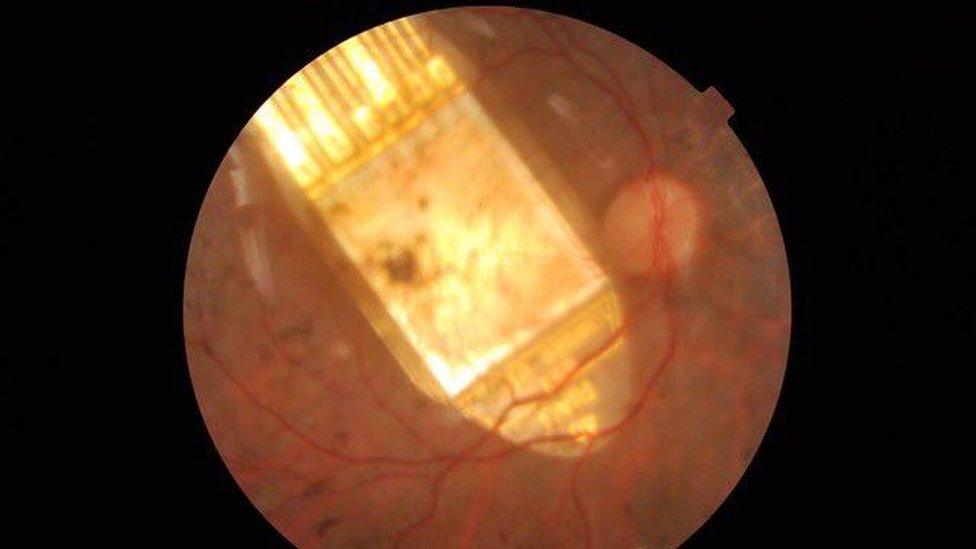

In the summer, Rhian travelled to Oxford for an operation to implant a tiny 3x3mm chip into her right eye.

The device replaces the light-sensitive retinal cells in the eye, and is connected to a tiny computer that sits underneath the skin behind the ear.

The small implant measures 3mm by 3mm

When it is switched on using a magnetic coil applied to the skin, signals travel to the optic nerve and then to the brain.

Rhian still had an intact optic nerve and all the brain wiring needed for vision, but her mind needed time to adjust to the signals it was suddenly receiving after being dormant for so long.

She explains: "It was a bit nerve-wracking. I didn't know what to expect.

"They sort of put the magnet to the little receiver there on my head and switched the receiver on. They said I might not get any sensation… and then all of a sudden within seconds there was like this flashing in my eye, which has seen nothing for over 16 years, so it was like, 'Oh my God, wow!' It was just amazing to feel that something was happening in that eye, that there was some sort of signal."

One of the first tests the doctors did was to check if Rhian could now see flashing lights on a computer screen in a dark room - she could.

The implant sits at the back of the eye and takes over the job of cells called photoreceptors

"What I was seeing was sort of a line at the top of my eye and at the bottom. But it was getting quite distracting because it was quite a slow flash really, so I asked them if they'd change the frequency. Now I've got more of a shimmer, rather than flashing lines, which is much less distracting and a little more accurate."

Next they checked if she could distinguish white objects on a black background - a white plate on a black tablecloth - which didn't go so well.

Rhian recalls: "I wasn't quite sure where the plate was. So I left that day with sort of mixed feelings, because the flashing was working but I couldn't see the plate on the table."

One test involved Rhian looking closely at a large cardboard clock to see if she could tell the time correctly

She returned the following day to repeat the failed test.

"They did the objects on the table and I could get them and I was so chuffed, I must have looked like a kid at Christmas! I was just locating a plate, a cup and a couple of shapes, but it was difficult because I didn't have any co-ordination. I haven't seen anything through that eye for so long, so I kept overshooting it a little bit - but we were getting there. I was just elated, really elated."

Next, it was time to go outside.

"I was absolutely terrified, because I didn't know what to expect at all. And I was thinking 'oh, I don't want to let anybody down, I don't want to let myself down…' But as it turned out, it was great.

"There was a car, a silver car and I couldn't believe it, because the signal was really strong and that was the sun shining on the silver car. And I was just, well, I was just so excited, I was quite teary!

"Being out in the real world, actually out in the street, you know, is far more useful, than locating flashes on a computer screen and doing the things in the lab. Just to walk under a tree and realising it'd gone dark was amazing, because I hadn't had that.

"Now, when I locate something, especially like a spoon or a fork on the table, it's pure elation, you know. I just get so excited that I've got something right. It's really just pure joy to get something right, because I've never done it before - well, not for the last 16 or 17 years anyway."

The surgical team at the Oxford Eye Hospital, John Radcliffe Hospital have been as delighted as Rhian with her progress.

Although the chip has the resolution power of less than 1% of one megapixel, which is not much compared to a standard phone camera, it has the advantage of being connected to the human brain, which has over 100 billion neurons of processing power.

Rhian Lewis, 49, who had been virtually blind for over a decade, tests a cutting edge electronic implant

Using dials on a small wireless power supply held in the hand, Rhian can adjust the sensitivity, contrast and frequency to obtain the best possible signal for different conditions as she continues to practise interpreting the signals and regaining her independence.

If the rest of the trial is successful, it's possible that this implant could be made available on the NHS. The team also hope that one day this technology can be applied to other eye diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration.

You can watch her story on Trust Me, I'm a Doctor on BBC2 at 8pm on Wednesday 6 January.

- Published21 July 2015

- Published3 May 2012