Will alcohol advice help us beat the demon drink?

- Published

- comments

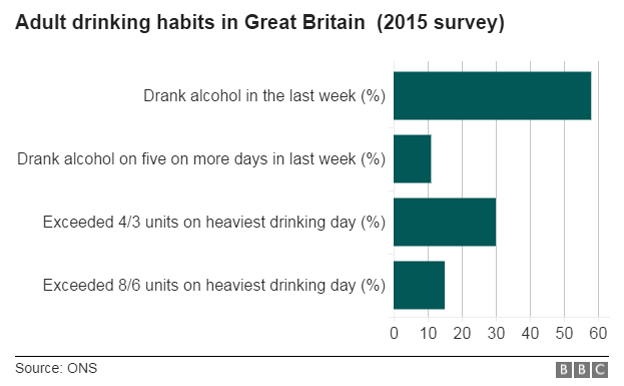

The uncomfortable truth is that many of us drink too much. One in three - when asked - admit to breaching the old alcohol guidelines.

The new ones published on Friday are even tougher. We are, in short, a nation who loves its booze.

It's not just a treat any more, it's a way of life. Sixty years ago alcohol was consumed largely in pubs, by men.

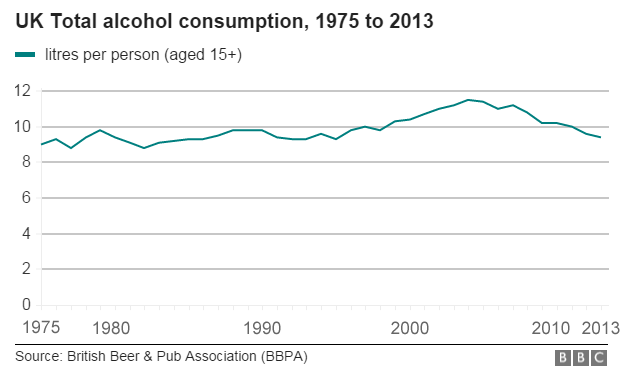

Now the amount we drink has more than doubled to just under 10 litres of pure alcohol a year - the equivalent of 100 bottles of wine.

There are a number of factors behind this - women drinking more and the strength of wine and beers being increased are just two - but perhaps the most significant has been the tendency to consume alcohol at home.

Two-thirds of all purchases are for consumption indoors rather than in pubs, bars, clubs and restaurants.

The new guidelines have been designed to discourage this everyday drinking culture.

Firstly, they reflect the latest scientific evidence that has been identified about the harm it causes, particularly in terms of cancer.

But secondly there has been a desire to present a clearer message on drinking. There is an acknowledgement that what has been said about it in the past has been a little confusing.

For example, the guidelines - from 1995 - talk about recommended daily drinking levels.

This, some claim, has suggested that it is safe and acceptable to drink every day. A man could, in theory, consume 28 units and not be in breach of the old guidelines even though most experts would argue this is too high.

And it was one of the reasons why doctors have subsequently recommended men drink no more than 21 units and women 14 units a week.

Want to know more?

The government guidance has been similarly opaque for drinking in pregnancy. While the advice says pregnant women should not drink, it then goes on to say that if they do they should keep it to a minimum of one or two units once or twice a week.

The new guidance has swept such inconsistencies aside. The aim has been to create simple and easy-to-understand recommendations.

So all adults have been told to drink the same amount - rather than the different limits that existed for men and women - and there should be several drink-free days a week and no binge drinking.

The question now is whether this will have the intended impact. As the graph below shows all through the 1990s drinkers ignored the warnings about booze and it was not until the economic crash - when disposable incomes were hit - that drinking levels really started dropping.

The hope now is that the fresh guidance will capitalise on this downward trajectory. But many experts believe this alone will not be enough.

Katherine Brown, director of the Institute of Alcohol Studies, said too many people remain unaware of official advice.

Instead, she has called for it to become compulsory for health warning labels to be included on alcohol products (at the moment it is only voluntary) and for there to be mass media campaigns to hammer home the message and make it "clear the risks people run" if they drink more than recommended.

Other steps, including a minimum price for alcohol, have also been put forward by campaigners.

The government says such measures are "under consideration". This could be just the start of a a new battle against the demon drink.