Why the government is going sweet on a sugar tax

- Published

- comments

Next month, the government in England is expected to publish its long-awaited child obesity strategy. The plan has been in the pipeline for some time - it was originally going to be published last autumn.

But even at this late stage there's still fierce debate within Whitehall about what should be in it.

At the heart of the debate is the merit, or otherwise, of a sugar tax. Health experts have been campaigning hard for one to be introduced - and even the government advisory body Public Health England has put a case for it, external.

But for much of the time since the election, ministers have been resistant. Until recently. There are now signs they're coming round to the idea. This much is obvious from the change in tone from the prime minister himself.

Earlier this month, he said he wasn't ruling out a tax, which is somewhat different from last year's statements that he "doesn't see a need" for it.

This should not come as a surprise: David Cameron's government has form on changing its mind when it comes to these sort of health dilemmas. During the last Parliament, ministers proposed plain packaging for cigarettes, then appeared to go cold on it before agreeing it was necessary.

A similar flip-flopping could be said to have happened over minimum pricing for alcohol (although that is still in the pending box as no final decision has been made).

Conservatives are naturally wary of introducing new taxes and accusations of the nanny state.

So what has influenced government thinking this time? The delay in publication has certainly allowed the experts to mount a vigorous campaign.

As well as the normal array of doctors and health chiefs, TV chef Jamie Oliver has also waded in. He set up an e-petition which saw more than 150,000 people backing a sugar tax.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

Meanwhile, NHS bosses have already announced they will be introducing their own "tax" in hospitals.

Understandably, no government wants to get caught on the wrong side of popular opinion.

But I'm also told that ministers have started to be persuaded by the evidence. One in five children is obese by the time they finish primary school. Include those classed as overweight and the figure jumps to one in three.

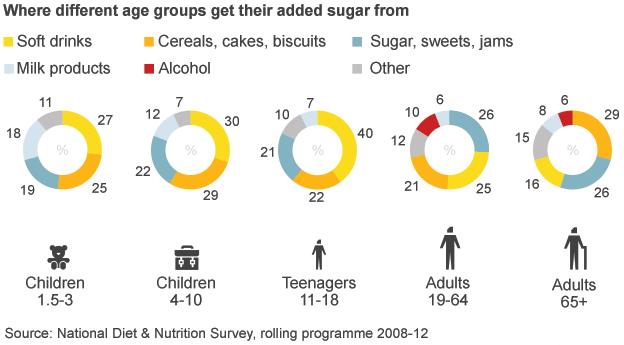

Children consume three times as much sugar as they should - with a third of that coming from fizzy drinks. And there is evidence it will work. In Mexico, consumption fell by 6% after a tax of 10% was introduced.

The impact of the 5p plastic bag charge is also in their minds.

But, of course, the obesity strategy is not just about a tax. Other measures, including a crackdown on shop promotions and advertising (again not natural territory for Tories) as well as a sustained drive to reduce the sugar content of food are also in the mix.

There will be measures to get people more active too, although the emphasis will be very much on diet as there is an acknowledgement that without curbing calories there is a limit to what physical activity can do.

It will be, in effect, an acknowledgement that society is geared too much towards unhealthy lifestyles.

This much is clear from the way we consume food. Just look at food promotions, which are heavily weighted towards unhealthy products. About 40% of expenditure on food goes on promotions, causing us to purchase a fifth more than we would have otherwise, according to PHE.

The result is an unhealthy diet. Last week, researchers at the Food Foundation produced a model of the typical family's diet, external.

Every member of the average family consumed too much sugar and saturated fat and too little of the good stuff - fibre, fruit and vegetables and oily fish. What is more, all but the youngest members were eating too much red and processed meat and salt.

It's no wonder that some in the field are describing obesity as the "new smoking" - and ministers are, bit by bit, being convinced.