Race to understand Zika link to baby microcephaly

- Published

An urgent global race is under way to establish how and why the Zika virus could be causing a devastating spike in cases of babies being born with underdeveloped brains in South America.

Brazil has reported around 4,000 cases of microcephaly since October - an unprecedented number.

The World Health Organization has declared a global public health emergency in response.

But experts are unsure what exactly is behind the rise.

Dr Anthony Costello, the WHO's expert on microcephaly, says finding an answer quickly is imperative.

"We must assume, given global travel and the like, that this could spread into many other populations as well.

"What we have picked up is a surge in cases of microcephaly in two areas where Zika virus has broken out. First in French Polynesia last year and now, to a much greater extent, in Brazil.

"We do not know about cases yet in other areas."

Zika virus has now hit more than 20 countries and the WHO believes it is likely to spread "explosively" across nearly all of the Americas, making the need for fast answers clear.

Dr Costello says there will be a lag time of several months to know if pregnant women in these newly affected countries are safe.

The race is on to find a better diagnostic test and a vaccine and treatment for Zika as well as establishing what is making these babies ill.

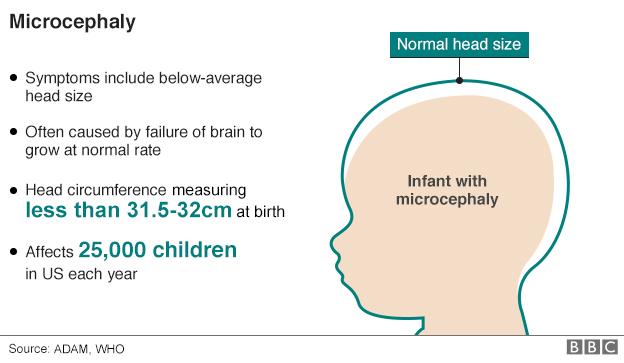

Microcephaly is not a new condition. In the US, official reports suggests two to 12 babies per 10,000 born each year have microcephaly - that's around 25,000 babies a year.

It can be caused by other infections caught in pregnancy, such as rubella.

Drug and alcohol abuse by expectant mothers are also factors.

And it can also be caused by rare genetic conditions.

The difficulty facing scientists is establishing what is behind each new case.

Research using animal models is needed to determine if Zika causes damage to an unborn infant when infection occurs in pregnancy and at what stage, as well as studies of pregnant women who have unfortunately been infected with Zika virus to determine the outcomes of their pregnancies.

Dr Costello said: "We desperately need to have better diagnostics for Zika virus so that we can look very carefully, if you get pregnant and you get infected, at what is the risk of getting microcephaly.

"At the moment we don't exactly know what the risk is."

He said although many pregnant women would, understandably, be very scared at the moment, they should remember that the risk of their baby having microcephaly was still very low.

"This is still a relatively rare occurrence and even if the rates increase, most women are going to get through pregnancy absolutely fine."

Babies born with microcephaly can grow up to have few or no complications. The impact it will have on their life depends on its severity.

An underdeveloped brain can lead to seizures, developmental delays, intellectual disability, problems with movement and balance, hearing loss and visual problems.

Because it is difficult to predict at birth what problems may lie ahead for a baby with microcephaly, they need close medical follow-up.

There are things pregnant women, or those who are likely to be pregnant, can do to protect themselves against the potential risk:

to consider delaying travel to areas affected by Zika

seek advice from a physician if they are living in areas affected by Zika

protect themselves against mosquito bites by wearing repellent and covering up

- Published1 February 2016

- Published31 August 2016