Why brains are beautiful

- Published

- comments

Fergus Walsh discovers why the brain is a marvel of evolution

When I picked up the human brain in my hands, several things ran through my mind. My immediate concern was I might drop it or that it would fall apart in my hands - fortunately neither happened.

Second, I was struck by how light the human brain is. I should say this was half a brain - the right hemisphere - the left had already been sent for dissection. The intact human brain weighs only around 3lbs (1.5kg) - just 2% of body-weight, and yet it consumes 20% of its energy.

The brain I was holding had been steeped in formalin, a preserving fluid, for about three weeks and is one of several hundred brains donated every year for medical research.

It was only after I'd got used to the feel of the brain in my hands that I could then start to wonder about how such a simple-looking structure could be capable of so much.

This brain had experienced, processed, interpreted an entire human life - the thoughts, emotions, language, memory, emotion, cognition, awareness, and consciousness - all the things that make us human and each of us unique.

You may think yuck, but I'm with the scientists and surgeon who declare: "Brains are beautiful".

The pathology team at the Bristol Brain Bank , externalhad kindly allowed us to film as part of the BBC "In the Mind" season, looking at many aspects of mental health.

My brief was to examine some of the latest advances in neuroscience.

There is a genuine sense of excitement among researchers about the direction and progress being made in our knowledge of the brain.

Fifteen years ago scientists knew that there were strong familial, inherited elements to some types of mental illness.

They also could see that some medications for mental illness were effective, but could not explain the mechanisms involved.

Prof Ed Bullmore, University of Cambridge

Now, in schizophrenia alone, more than 100 genetic links, external have been implicated and the language of brain circuits has arrived.

Several distinct conditions of the mind - autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia - have been found to share, external some of the same genetic risk factors.

Prof Shitij Kapur, Dean of the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience , externalat King's College London told me: "The brain used to be like a black box. Now we can explain why treatments work, and when you know that you can begin to design better ones."

Although many genes are known to increase a person's vulnerability to mental illness, what actually causes it is everything else - the experiences of life.

Prof Kapur put it like this: "It is humbling to know that genetics do not determine the outcome. You can have many of the genes of risk and not get the disorder and have none of them yet succumb to it."

Just as the Human Genome Project transformed knowledge of biology and genetics, a similar revolution is underway in scientific understanding of the brain.

The international Human Connectome Project (HCP), external aims to unravel how the brain is wired and the function of neural networks.

Ed Bullmore, Prof of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, external, who is on the HCP advisory panel told me: "Connectome is a word that has only existed for about 10 years, and summarises the ambition that we might be able to map the entire network of the human brain; it is exciting to see that suddenly it looks like it might be possible."

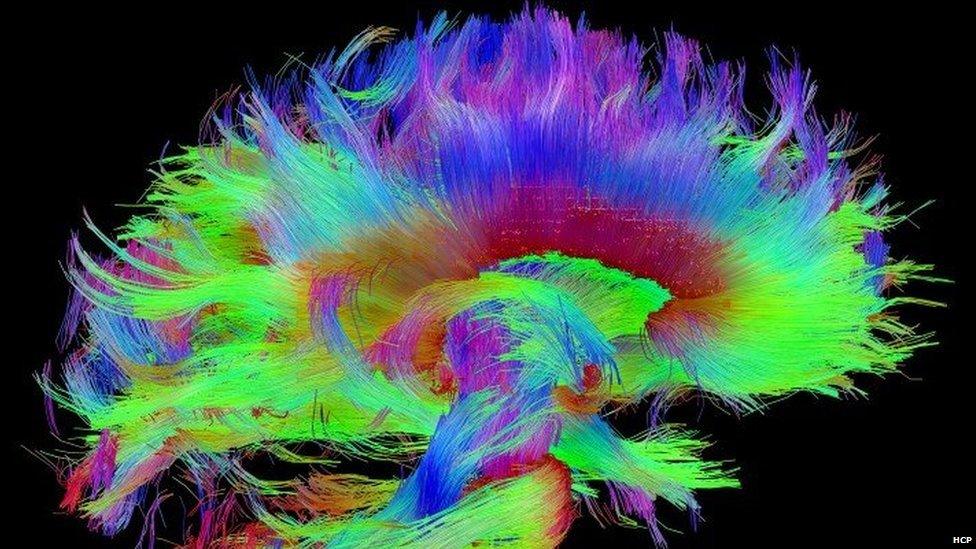

The images produced by improved brain scanning techniques are stunning., external

A wiring diagram of a human brain, revealing its network of connections

Thousands of thin coloured wires, like spaghetti, show the cabling of the human brain - with each wire representing a bundle of axons or nerve fibres.

The image is reminiscent of one of those depicting flight paths across the planet - all linked by a number of key airport hubs.

The brain also has several hubs - regions that are highly connected. Prof Bullmore explained that people with schizophrenia tend to have fewer brain hubs so their neural networks are somewhat less connected than would be found in a healthy brain.

By studying the development of brain networks in adolescence, when brain hubs are becoming strengthened and consolidated, Prof Bullmore and his team are hoping to unravel the developmental changes that contribute to mental illness.

He said: "If we can understand the genetic mechanisms that drive network development to go off on a different path that leads to schizophrenia, then we can design new drugs - not just those that damp down the symptoms of hallucinations and delusions, but we may be able to identify treatments that prevent an individual at risk of schizophrenia from developing the condition or to improve the long term prognosis of patients."

In another part of Cambridge, being gentled rocked inside an incubator at body temperature, I was able to see dozens of so-called organoids - miniature developing human brains.

These balls of tissue strongly mimic the early stages of foetal brain development - so represent another important approach towards enhancing our understanding of the most complex biological structure on the planet.

The technique for growing organoids was discovered by Madeline Lancaster, external, a developmental biologist, now based at the Medical Research Council's Laboratory of Molecular Biology.

Skin cells are taken from an adult donor and then reprogrammed to become early stage neurons. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), external are widely used in research to create patient-specific models of disease.

Madeline Lancaster devised the means to coax the cells to develop in 3D and, as a result, to become mini-brains.

When taken from patients with mental illness, they can be used to investigate the origins of their disease.

She told me: "The human brain is the organ which is most different from other forms of life and so some questions about how it functions and why it goes wrong just can't be answered in animal models such as rodents. We have high hopes that organoids can give us real insights into how mental illness develops.

"I think it is a really huge step towards some hopefully amazing breakthroughs in what has been a desert in the field of biomedicine. Mental health disorders have been really lacking in terms of new treatments to treat these really devastating disorders"

More than a dozen organoids - miniature developing human brains - can be seen at the bottom of this flask

So when will this research lead to better treatments? Prof Kapur of King's College London urges patience.

He reminds me that the "war on cancer" was declared in 1971 (in a speech by President Nixon), and that it took three decades for major advances to reach most patients.

"In the next five to 10 years we'll be able to use genetics and neuroscience to target treatments better to patients. Based on the knowledge we have now we could also have new medications, not for an entire illness for a subset of autism or schizophrenia."

He also stressed that there is not a drug for everything: any new medications would be just part of the answer with psychological treatments playing a vital role in improving outcomes.

It was a privilege to be allowed to hold a human brain. The experience increased my respect for this piece of tissue, which can be so easily damaged with catastrophic consequences.

It also reinforced my sense of wonder at this masterpiece of evolution. Brains really are beautiful.