Mental health care provision - failings and opportunities

- Published

You don't need to go further than the first paragraph in the foreword of the mental health taskforce report to find a bleak assessment of the current state of services.

People with mental health problems have been "stigmatised and marginalised", it says, and services have been "underfunded for decades".

The report, compiled by a panel of NHS and independent experts and due to be published on Monday, does acknowledge that the picture has started to change.

It points out that attitudes are improving and there is now a cross-society consensus on achieving change.

But it says the the transformation of care will take ten years - and the report marks just the beginning of the process.

The 59 recommendations of the report, all of which have been accepted by the NHS England leadership, suggest a determination to shake up all aspects of mental health care.

The aim is to have most of the implementation in place by 2020/21, but even by then the report authors admit that parity of esteem between mental and physical health will not have been achieved, though the process will be some way down the track.

'Chronic underinvestment'

The report does not always make comfortable reading for ministers in the coalition government.

A mental health strategy in 2011, says the report, was widely welcomed at the time but it did not successfully address inadequate provision and worsening outcomes.

There has been "chronic underinvestment in mental health care across the NHS in recent years".

The extent of the financial squeeze and divergence of mental and physical health budgets is underlined by findings from BBC Freedom of Information requests.

These show that the income of mental health trusts in England fell by 2% in 2014/15 after taking account of inflation.

The Health Foundation think tank says that in the same year the income of acute trusts - hospitals dealing mainly with physical health conditions - rose by 2.6% in real terms.

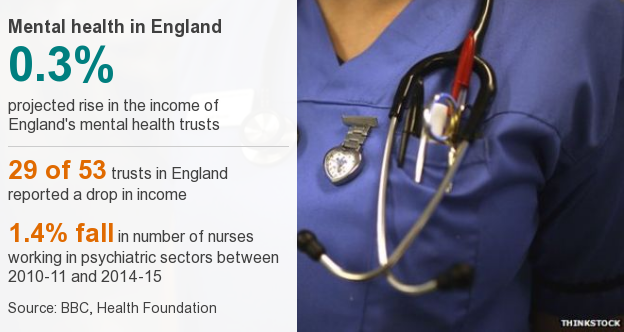

In the current financial year, the BBC research shows mental health trust total income is set to rise just 0.3%.

Some 29 out of 53 trusts which responded expect that by the end of the financial year their budgets will be lower than the previous year.

Mental health in England

0.3%

projected rise in the income of England's mental health trusts

-

29 of 53 trusts in England reported a drop in income

-

1.4% fall in number of nurses working in psychiatric sectors between 2010-11 and 2014-15

The Department of Health points out that local councils and other organisations also provide mental health services and these are not covered in the BBC research.

But mental health trusts account for at least 80% of spending in this area.

Ministers and the head of NHS England, Simon Stevens, will argue there will be a real annual funding increase of £1bn for mental health by 2020/21.

This will be in addition to the £280m per year already pledged to children and adolescent and perinatal services.

Even so, the £1bn is not "new" - it comes from the £8.4bn extra already awarded to NHS England for 2020/21 by Chancellor George Osborne.

'Black box'

Another problem identified by the report is keeping track of money spent on care of patients with mental illnesses in England.

There is said to be "little or no national data" for how much of the money is used at local level.

Mr Stevens talked of a "black box" with regard to data and has demanded more transparency.

He knows that if light is not shed in this area it will not be possible to assess progress.

The ambitions for the next few years are impressively set out, including the provision of liaison mental health services in all A&E units.

The report is honest in cataloguing the failings of the past.

But it is interesting to note that the year for delivering the targets is 2020/21 which is after the next general election.

- Published15 February 2016

- Published14 February 2016

- Published12 February 2016

- Published12 February 2016