Is enough being spent on the NHS?

- Published

- comments

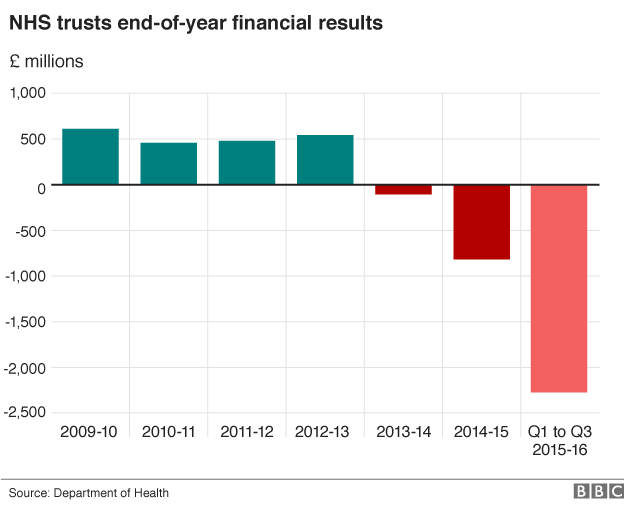

The NHS in England is in the grip of arguably its biggest financial crisis in its history.

NHS trusts have been racking up deficits en masse. Regulators and ministers are talking tough, telling hospitals (which are almost entirely responsible for the deficit) to get their house in order.

But another way of looking at it - and it's something that has been put to me often on Twitter recently - is that rather than the NHS overspending, the deficit is simply a sign of underfunding.

Now the government will quickly point out that it is increasing the budget this Parliament - by just over £8bn in real terms. And that is certainly generous when you look at what other departments have had.

But a counter-argument is that the increase is just a fraction of what the health service actually needs, given it is grappling with issues like the ageing population, obesity and the cost of new drugs. These factors are sometimes called NHS inflation and are said to increase costs by about 4% a year - well above the wider economy's rate of inflation in recent years.

That is why in return for the extra money, the NHS has promised to make savings - £22bn by 2020. Suffice to say it's a monumental ask.

'Survive and thrive'

So could - indeed should - the NHS get more? There is certainly a growing number of influential voices arguing it should.

This week Prof Don Berwick, the government's former patient safety adviser, raised the issue.

Speaking at an event in London, he gave a typically blunt appraisal of the challenges facing the NHS and government. His comments attracted the attention of the media because he suggested the government had been wrong to impose the contract on junior doctors.

But what wasn't picked up so widely was his criticism of the spending plans and the impact it was having on the ability of the NHS to, as he put it, "survive and thrive".

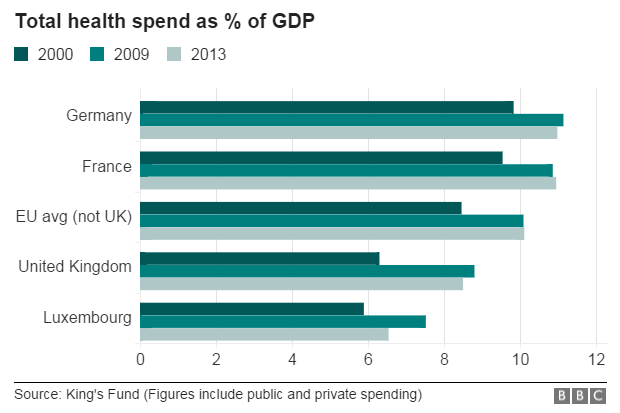

He told the audience of health professionals that the level of funding in the NHS may make the government's ambitions for the health service, which of course include seven-day services, "impossible". In doing so he highlighted the amount spent as a proportion of GDP (which stands for gross domestic product and measures the size of the economy).

This is a widely used way of comparing health spending across different nations. It was used by Tony Blair when he spoke about increasing health spending in the early years of his government.

In 2000 the UK spent 6.3% of its GDP on health once public and private spending is added together (this is done to take into account the social insurance schemes that exist in some countries). Under Labour this rose and by 2009 it had hit 8.8%, which was above the EU average in 2000.

But the boom years had also prompted other nations to increase their spending so that by 2009 the EU average (for the 14 other members compared in 2000) was now 10.1%.

Of course since then the global economy has had to cope with turbulent times and so spending on health has stopped rising. In the rest of the EU it has remained pretty constant, while in Britain it has fallen - as the graph below shows.

Now what is interesting is what happens if you look at the potential impact of the government's spending plans for this Parliament. This is something the highly respected King's Fund chief economist John Appleby has done, external.

His number crunching suggests that while the budget is going up as a proportion of GDP, spending will actually fall further because the economy will grow at a faster rate than the NHS budget.

If both were to match each other it would mean another £16bn being available by 2020, while if it was to be brought up to the EU average another £43bn would need to be ploughed in.

His conclusion? More could certainly be spent - it just comes down to the political choice of higher taxes, less spending elsewhere or slower deficit reduction.