Meningitis B vaccine: Hearts v heads

- Published

Babies are most at risk of meningitis B infection

Deciding which children should get a life-saving vaccine against meningitis B is a battle between hearts and heads.

The effects of meningococcal infection can be devastating.

In the space of a few hours, the bacterial infection can leave a child fighting for their life in intensive care.

They can be dead within 24 hours.

If it infects the brain and spinal cord to cause meningitis or sepsis in the blood, then even survivors could face life-long disability.

It is something any parent would try to prevent happening to their child, and more than 800,000 people have signed a petition calling for the meningococcal B vaccine to be offered to all children under 11.

It is the most popular petition in parliamentary history because of this picture.

Faye's mother Jenny published this picture of her daughter to raise awareness

It was shared by Jenny Burdett, whose two-year-old daughter Faye died from the infection last month.

She was too old to get the vaccine, which is given in the first year of life, but only to children born after May 2015.

So why isn't it given to more children?

This is the point where the "heads" can appear heartless - as the answer is mostly about money.

While any child's life is priceless, a publicly funded NHS aims to ensure it spends its money on the treatments that give the most benefit, whether they are cancer drugs, hip operations or vaccines.

And the meningococcal B vaccine is spectacularly expensive because of the complicated way it is manufactured.

'Borderline'

The government's expert advisers on vaccines have told the BBC that the evidence was "pretty borderline" for giving the vaccine to anyone and a plan was initially rejected.

It took a cut-price deal arranged between the Department of Health and GlaxoSmithKline for an immunisation programme for the most at-risk age group - the under-ones - to be introduced.

The vaccine is so new that we do not know how many lives are being saved.

The UK is also the only country to have introduced the vaccine, so the whole world is waiting for answers to know how effective this jab is.

We know the programme vaccinates about 700,000 infants each year in an age group that has just over 100 cases and six deaths each year.

Remember, the cost-effectiveness in this high-risk age group was classed as borderline.

Running a catch-up programme for all two-to-10-year-olds (one-year-olds would have been vaccinated in the first year of the immunisation scheme) would require giving two doses of the vaccine to more than five million people.

We know Men B gets rarer as children get older, apart from a teenage blip.

The data on deaths from meningitis B has not been published, but senior figures have told me that fewer than 100 infections would be prevented and about six lives saved.

That is why heads appear to be winning the battle with hearts within government.

And these are not the only costs.

One of the reasons cited for the vaccination programme going ahead in infants was because it could be given during the same appointment as for other childhood immunisations.

A catch-up campaign for under-11s would require extra resources - probably a combination of GP and primary school campaigns.

The closest comparison is the huge effort being made to vaccinate all children between the ages of two and 16 against flu.

But that is taking years to introduce and so far the vaccination has been routinely offered to only two, three and four-year-olds, external.

The idea of vaccinating under-11s also assumes there are 10 million doses of the vaccine waiting to be given to children.

As anyone who has tried to get the jabs privately knows there is a shortage. The relatively small private market should have new supplies by the summer. Getting millions of jabs would take much longer.

As one official told me: "Even if we had the money, we wouldn't have the vaccine."

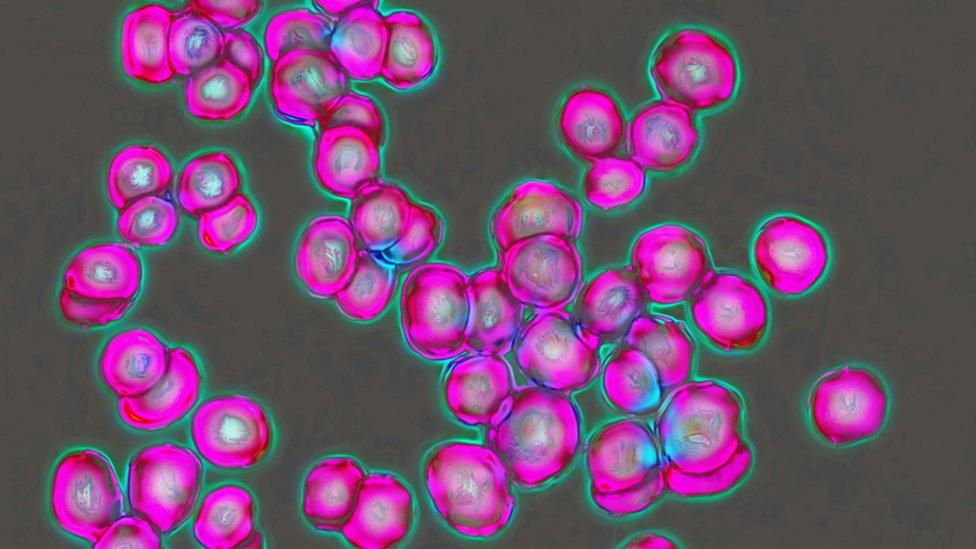

Meningococcal bacteria

Some doctors have also raised concerns about unknown safety risks, as no country has immunised large numbers of people.

Trials on thousands of people have clearly shown the jab is safe, but some side effects appear only after tens or even hundreds of thousands of people are vaccinated.

Narcolepsy induced by the swine flu, external vaccine or an old rotavirus vaccine and bowel obstructions, external are two examples of unexpected side effects.

It is another reason there is reluctance to vaccinate millions of children.

Wrong age, wrong meningitis

But away from the money there are other arguments made for not giving the Men B vaccine to under-11s.

One is that it may be better to vaccinate slightly older children instead.

Teenagers harbour the bacterial infection and unwittingly spread it to children.

Immunising this age group - as happens with Men C - could protect people of other ages too.

Doctors are also more worried about another, even more aggressive, type of meningococcal infection that is spreading rapidly.

Meningococcal infections have natural cycles, becoming more and less common over decades.

At the moment Men B is becoming rarer. In the early 2000s there were more than 1,600 cases in England, compared with about 400 cases in 2014.

But an aggressive strain of Men W is currently spreading - going from 17 to 200 cases in the space of five years.

It is twice as deadly as Men B and is the strain that is causing most alarm and changes to vaccination programmes.

Deciding who should get a Men B jab is an emotive issue.

The evidence will change with time once the data on lives saved by the immunisation programme is published.

And there are discussions about whether the rules on cost-effectiveness do not work for preventing childhood diseases and need to be changed.

But for now there seems little appetite to let hearts rule heads.

Follow James on Twitter, external.