Zika vaccine possible 'within months'

- Published

Tulip Mazumdar reports from a lab where scientists are trying to develop a Zika vaccine

A Zika vaccine could be ready for human trials later this year, according to the man in charge of the US government's research programme.

Dr Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, hopes to start testing a DNA vaccine by September.

About 100 Americans have been diagnosed with Zika after returning from affected countries.

Scientists at the institute helped develop a vaccine for Ebola.

They are now trying to do the same for Zika, with a special focus on pregnant women because of the strongly suspected link between the virus and babies being born with under-developed brains.

Dr Fauci said he's hoping human trials will start in America soon.

"We will have a vaccine ready to go into humans to test - not to distribute - but to test for safety and whether it induces a response that you can predict will be protective.

"That phase 1 trial I believe will likely start towards the end of this summer or early fall"

But phase 1 trials are only the start of a potentially lengthy process.

If the outbreak starts to wane, as happened in the advanced stages of the agency's Ebola vaccine trials, it will not be possible to conduct big enough studies to confirm how effective the vaccine is in at-risk populations.

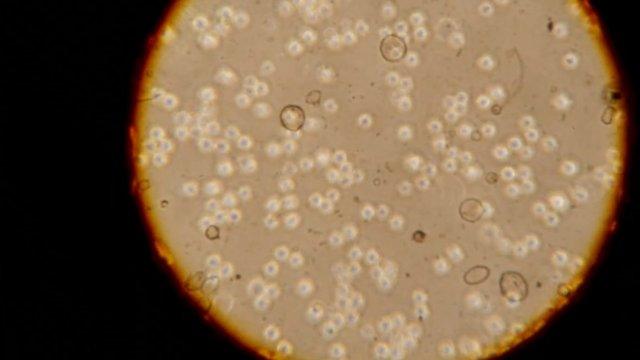

The Zika vaccine in development uses synthesised genetic information from the virus, rather than live virus, to trigger an immune response in the body.

So if a person then becomes infected with the virus, their body is already primed to fight it.

Developing new vaccines can take decades. But scientists working at the labs in Maryland believe they can fast-track the process because they had already been working on a vaccine for West Nile virus, which is spread by the same Aedes aegypti mosquito.

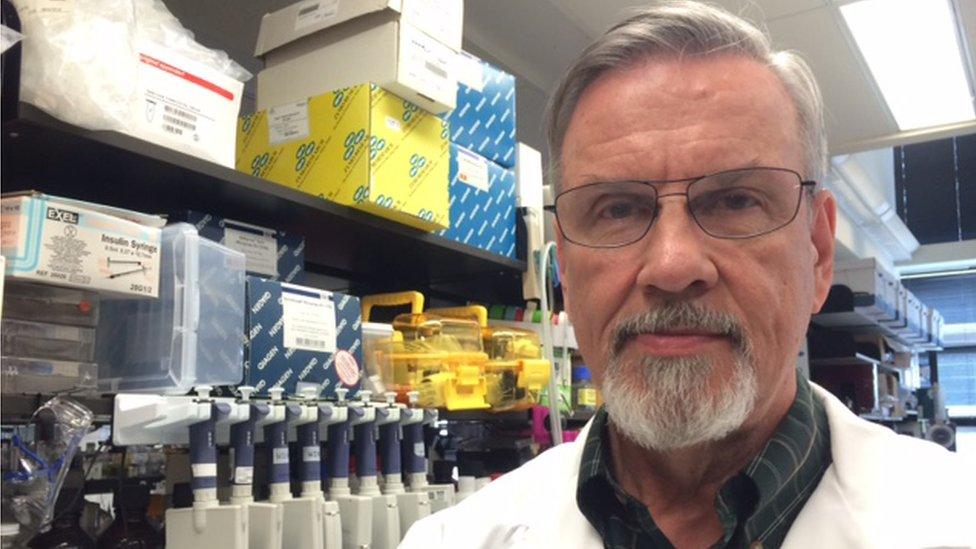

Dr Barney Graham, deputy director of the National Institutes of Health Vaccine Research Center, where the vaccine is being developed, said: "The challenge is that we don't know a lot about Zika, but we know a lot about other flaviviruses. Zika is one of the flaviviruses."

"Vaccines are generally not made quickly. We still don't have a vaccine for some viruses that have been around for 70 or 80 years."

But he added: "There are new technologies now. DNA vaccines can go quickly - we've done it before for West Nile, for H5N1 (bird flu) for Ebola and HIV."

The vaccine being developed at the NIH in Bethesda, just outside Washington DC, is one of two of the most advanced Zika vaccines in development.

The other is being developed by Bharat Biotech, an Indian company based in Hyderabad.

Dr Fauci said the American vaccine would focus on pregnant women, and women of childbearing age, with a longer-term goal of offering a vaccine to everyone, particularly if that link to microcephaly is confirmed.

He said the world had been in a similar situation in the early 1960s, when rubella was causing about 20,000 birth defects a year, after pregnant mothers became infected with the relatively mild German measles infection.

"As soon as we developed a rubella vaccine and started vaccinating everyone when they were children, the incidence of congenital rubella syndrome essentially disappeared.

"This is what we hope will happen with Zika."

However, it is already too late for the thousands of babies thought to be affected by this mysterious virus.

And despite the best efforts of scientists at the NIH, the very earliest a vaccine could be widely distributed is around 2018.

follow @tulipmazumdar on Twitter

- Published4 March 2016