'Exciting' new genetic test for child cancer patients

- Published

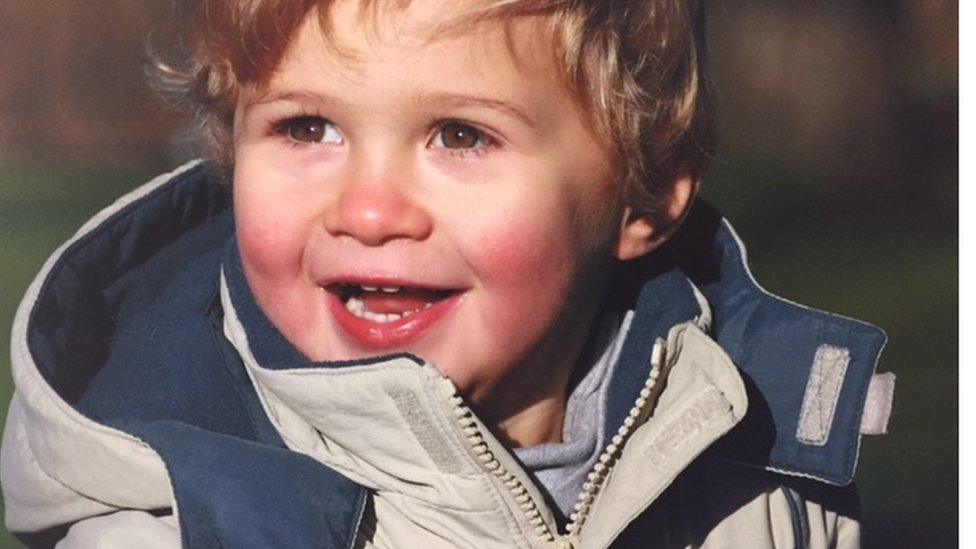

Christopher Capel's death from an aggressive brain tumour inspired his parents to raise money for the new test

UK scientists are beginning work to genetically test tumours from children with cancer.

They hope this will give younger patients access to newer, more personalised medicines and further improve survival rates.

The new test analyses changes in 81 different cancer genes.

Scientists say it should lead to "a more level playing field", and accelerate children's access to important new drugs.

The testing is based at the Royal Marsden NHS Hospital in London and will reach 400 children from around the UK over the next two years.

The implementation of the test has been funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR).

Aggressive killer

A charity called Christopher's Smile - set up by a couple whose only child died from an aggressive brain tumour just before his sixth birthday - also provided more than £300,000 to develop the test.

Karen and Kevin Capel, Christopher's parents, said: "This is the first real step towards personalised cancer medicine for children.

"Christopher was treated for a generic kind of tumour. Hopefully children in the future will know exactly what kind of tumour they have.

"It almost felt like the treatments were going to kill our son, rather than the cancer.

"He had been a healthy, happy, very sporty four-year-old. But he turned into a child who couldn't speak or feed himself, and lost a huge amount of weight.

"He wasn't the child he'd grown into at the age of diagnosis. We're striving to get away from this for other children."

'Incredible advance'

Cancer tumours are rare in children so, without a big patient population, there is less of an incentive for pharmaceutical companies to conduct clinical trials.

This means they risk missing out on innovative treatments which target the cancer cells, leaving healthy ones alone.

Prof Louis Chesler, who is leading the genetic testing research, said: "Children often don't have equal access to the most modern and potentially beneficial cancer drugs.

"The cost of developing these gene-targeted drugs is very high. They tend to go to adults first, where more people are being treated and results can be seen more quickly.

"This test is an incredible advance, because it will define all the genetic changes in the tumour with great clarity.

"That gives clinicians an enormously powerful tool - helping them pick the right drugs for children, and establishing that they are effective as quickly as possible.

"And children's cancers are genetically more simple than adult ones, so ultimately these drugs have a chance of being more effective in children."

The test aims to give scientists and doctors detailed genetic information about a child's tumour within a few weeks of diagnosis.

It will enable them to make a stronger case for using targeted drugs on some young patients, possibly saving them from the side-effects associated with conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Jack Daly and his mother Helen talk about the lasting effect radiotherapy had on his life

Brain damage

Jack Daly, 14, from Wokingham, survived a brain tumour which was detected when he was seven.

Radiotherapy helped save his life - but has left damaging after-effects.

Jack said: "My motor skills aren't very good. I have to have help getting dressed for school.

"My balance isn't very good - I'm clumsy and fall over. I struggle at school, and with friendships sometimes."

Jack and his mother Helen have supported the Capels with their fundraising - and hope the test will make a huge difference to the quality of life for children in the future.

Helen said: "People don't really see there's a problem because Jack's cancer is over. He's not in a wheelchair. He hasn't got bandages on.

"If you look at Jack, he's a regular teenage boy. But underneath there are problems because of brain damage from the treatment."

- Published11 February 2014