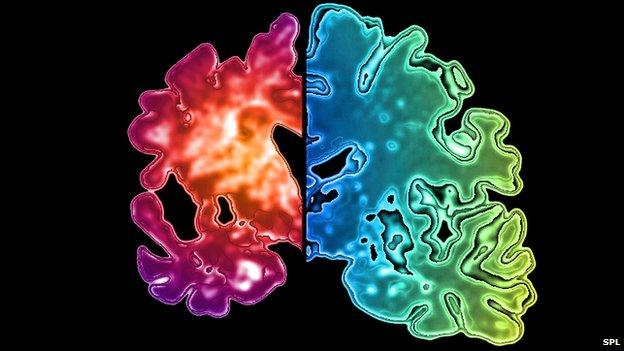

Dementia threat 'may be less severe' than predicted

- Published

The predicted explosion of dementia cases may be less severe than previously thought, a study in Nature Communications suggests.

Researchers looked at three areas of England, 20 years apart, and found new rates of dementia were lower than past trends would suggest.

They say improvements in men's health is the most likely explanation.

But charities warn against complacency, with more than 200,000 dementia cases diagnosed each year in the UK.

'Cautious optimism'

Researchers, funded by the Medical Research Council and dementia charities, interviewed about 7,500 people aged 65 and over living in Cambridgeshire, Nottingham and Newcastle in the early 1990s.

The whole process, which included detailed questionnaires about cognition and lifestyle, was repeated in the same way two decades later.

They found rates of new cases of dementia had been fairly steady in women over this time, but had fallen in men.

Extrapolating their findings to apply to the rest of the UK, they say there would be 40,000 fewer cases of the disease than estimates put forward two decades ago would suggest.

Scientists admit they are unsure exactly what lies behind this trend but say it could be that men have become better at looking after themselves.

For example, better heart and brain health - with fewer men smoking, less salt used in food, and a greater emphasis on exercise and blood pressure medication may have helped, they say.

They acknowledge it is hard to decipher why the same trends are not apparent in women, but speculate men may be catching up on health gains that women already experience.

Despite this, they warn that other factors - such as rising levels of obesity and diabetes - may reverse this trend in years to come.

Prof Carol Brayne, at the University of Cambridge, and part of the research team, said: "I'm pretty optimistic that it's stabilising, but if we don't further improve health, then we would expect the numbers to go up with further ageing of the population, so it's a sort of cautious optimism."

Scientists say the most important finding is that a rise in dementia is not inevitable and can be fought.

And they call for a better balance of funds so more money is put into prevention in mid-life.

Meanwhile, Dr James Pickett, head of research at the charity Alzheimer's Society, said the research was encouraging.

But he added: "People are living for longer, and with other risk factors such as diabetes and obesity on the rise, there will still be over 200,000 new cases of dementia each year.

"That's still an enormous number of people who require better information and health and social care support."

Other experts point out the way dementia is diagnosed has changed over time and initiatives focusing on spotting the signs of dementia earlier may offset any reductions seen.

- Published16 July 2013

- Published21 August 2015

- Published21 February 2015