Inside England's only gender identity clinic for children

- Published

Colin with his advice for anyone in his situation.

It is England's only clinic for children experiencing difficulties in the development of their gender identity.

The Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Centre, external in north London has been going since 1989 but this week I became the first journalist to be allowed access to its clinical rooms and some of its staff and patients.

To look at the centre from the outside it is nothing impressive. It resembles an office block.

But what happens inside is crucial to the happiness of every child who goes in seeking help, guidance and support.

The reception area is welcoming: warm yellow walls with two smiley receptionists who are courteous in their approach. In the waiting room, there are a couple of children in school uniforms, one munching on an apple, the other staring straight ahead as if deep in thought.

The staff here understand it must be a daunting experience for any child to come and wait to speak to psychologists and psychiatrists about their innermost feelings.

About 1,400 under-18s were referred to the service in the past year

They work hard to provide them with comfort through a collage of wall paintings featuring animals and other furry objects.

Up three flights of stairs, I am introduced to Dr Polly Carmichael, the woman in charge and one of the country's leading clinical psychologists in the area of transgender children.

'Real phenomenon'

"It's important that we make people feel welcome here," says Dr Carmichael.

"Every young person who comes to the service is an individual and it's really about getting to know them and creating a therapeutic space where it feels safe to think about all the alternatives and choices they may have."

Critics of the service often suggest an irresponsibility on behalf of the staff for talking about transgenderism to children and in some cases agreeing to the use of hormone blockers, or as they're called in the medical world, hypothalamic blockers.

Dr Carmichael rejects those criticisms: "This is a real phenomenon - there are young people who feel incredibly distressed around their gender identity and we start from a place where we accept that this is real and respected, but not one where we assume what the outcome will be, or what path that person will ultimately choose."

According to figures from the clinic, 32 children under the age of 16 were prescribed blockers last year, compared with 41 in the previous year.

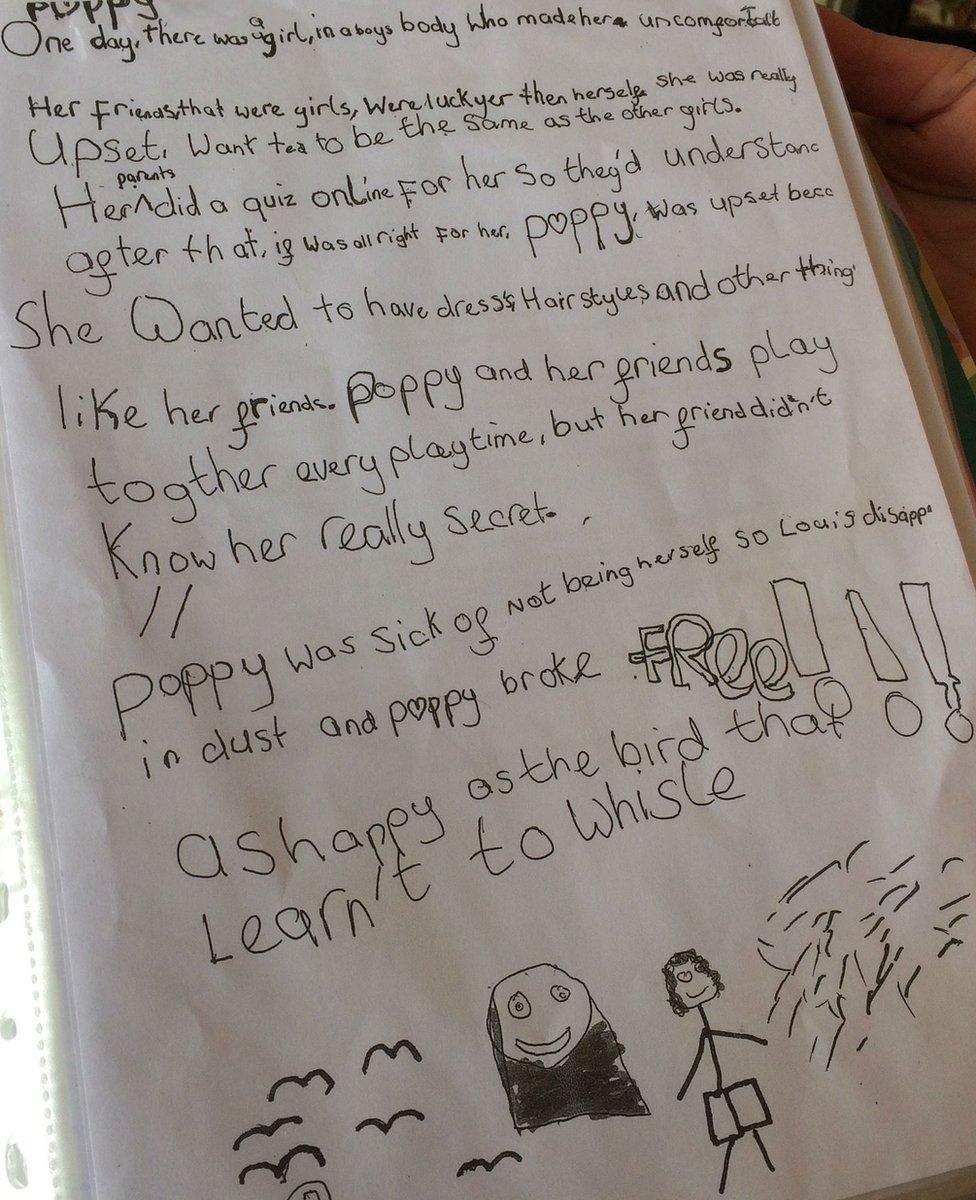

Poppy was nine when she transitioned from male to female

'Gender different from sexuality'

The corridors are long and lined with brown doors, all leading to either a clinical space or an office. One of the rooms I'm shown has toys scattered on the floor for those patients who are particularly young - bright building blocks and cuddly animals to put them at ease.

In another room across from the lifts sits 16-year-old Colin and his mum Jane. Colin transitioned from female to male two years ago and describes himself as a gay male. I'm given permission to sit in on a session between him and child psychiatrist Dr Victoria Halt.

The purpose is to see how Colin is doing with his transition and whether he's experiencing any distress or anxiety. In Colin's case it has been a smooth ride so far and he comes across as confident, happy and content.

He begins to explain that gender and sexuality are not synonymous.

"Gender is between your ears and not what's between your legs," he says.

"I feel like your gender identity is something really innate within you and it has no correlation to your body... like when I get periods then it's just something that happens to my body - it's not like this is a woman thing, this is just a thing."

He tugs at his t-shirt to pull it away from his breasts. He tells me he's wearing a chest binder - a sort of bra that presses down on any breast tissue to create a flat-looking chest.

"It's excellent for making people perceive me and my gender correctly but it can also cause a lot of back pain and if I wear it for too long then I've known people who have broken ribs from them.

"But I would rather be in pain and uncomfortable than look like a woman."

'I don't want to grow a beard'

Jessica has been having nightmares about growing up a man

Read more about two of the UK's youngest transgender children.

Cross-sex hormones

About 1,400 young people under the age of 18 have been referred to the Gender Identity Development Service over the last year.

Three children aged three were referred to the clinic in the past year, compared with none in the previous year.

Dr Carmichael says she's noticed that those transitioning are getting younger.

"Young people [are] making the full social transition - that means living full-time in their preferred gender inside and outside the home - at earlier ages," she says.

"It's something that comes through from those we've seen coming here in recent months."

The clinic says it prescribed hormone blockers to 32 children last year

At 16, someone can decide to take cross-sex hormones to look more like the gender they identify with, and at 18 can opt for surgical intervention.

Those procedures don't happen here. Patients are sent to University College London Hospital but the key decisions about what is right for them and how they should move forward are concluded in this building.

Children and their families have to wait around nine months before being seen by experts here. I meet Poppy - a nine-year-old who has transitioned from male to female and is on the waiting list.

"When I was little I used to go to my wishing well in the garden, throw some stones down there and wish I was a girl and that wish came true," she tells me.

"I didn't feel like myself as a boy and didn't feel right and something felt wrong inside. I'm so happy now."

To critics this is all about interfering with nature. But staff here insist that each case is different and that the media have created an illusion that this is happening on a mass scale when actually it is only occurring in a small proportion of the population.

For details of organisations that can provide help and support with gender identity, visit BBC Action Line.

- Published3 May 2016

- Published7 March 2015

- Published19 August 2015