The NHS: How bad will it get?

- Published

Look at almost any measure of performance, and the NHS in England is getting worse.

Waiting times for cancer care, accident and emergency units, ambulances and routine operations are all rising, and targets are being missed left, right and centre.

But just how bad is it? And how much worse will it get? Answering the first is relatively easy, the second not.

You could make an argument to say the NHS has lost a decade and is back to where it was 10 years ago, more or less.

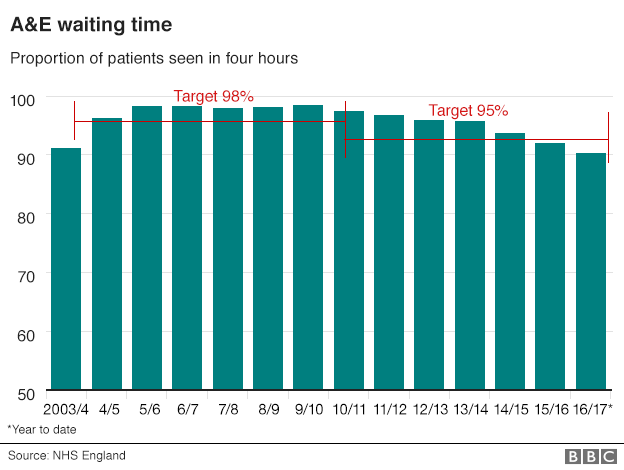

In A&E, the proportion of people waiting over four hours for treatment is at its worse level since 2004.

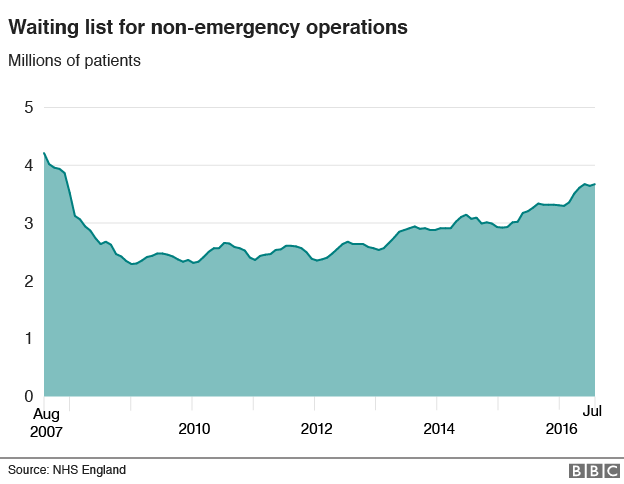

Waiting lists for non-emergency treatments, such as knee and hip operations, have not been so high since 2007.

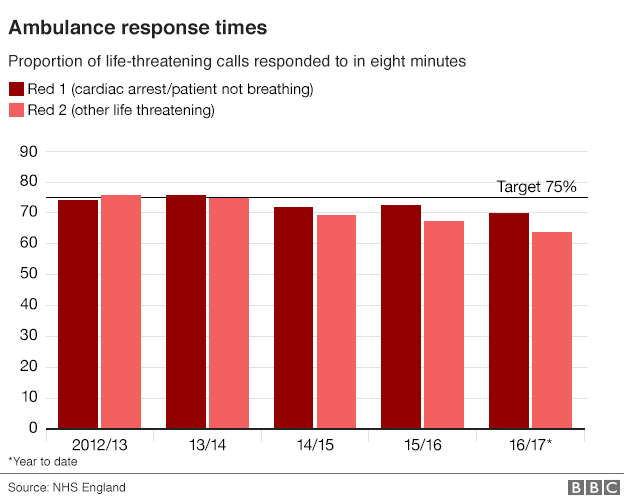

Ambulance response times are harder to judge, the way they are measured has changed and is changing again. But it is clear there is a downward trend.

And this is not unique to hospitals - it is just that there is better data on them than on community services. Nor is it an England-only problem. The pressures are being felt in the rest of the UK too.

Of course, there is some context, which NHS England and the government are increasingly highlighting.

Even with the declining standards, performance still compares pretty favourably with other health systems.

NHS medical director Prof Sir Bruce Keogh made an impassioned defence of the situation, at an event hosted by the King's Fund in London this week.

He said even on current A&E performance, the NHS was still outperforming "every other health system", while care for trauma, heart attacks and strokes still compared favourably with the very best.

That may be true. But for how long? How far will performance drop for waiting times in particular?

These are all questions I have been putting to a number of senior leaders in the NHS in recent weeks, and no-one seems really sure.

The downward trend is gradual but pretty consistent - and a bad winter with lots of flu (rates have been pretty low for a few years) would accelerate the deterioration.

Dr Cliff Mann, who has recently stepped down as president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, says the common denominators across all areas are rising demand and the problems hospitals are facing discharging patients once they are admitted.

"We simply can't get patients out quickly enough," he says.

The problem he is referring to is delayed transfers - when patients are ready to leave the hospital but cannot because care in the community is not available.

The number of these delays has risen by a quarter in the past year.

Until this problem is resolved, hospitals have little hope of speeding up waiting times.

But tackling delays is a complex issue. They can be experienced for a variety of reasons - waits for a care home place, home help with washing and dressing or district nursing.

All have felt the pinch as budgets have been squeezed.

Councils, which are in control of care services, have seen their funding cut, and while the NHS budget has been going up, the annual rise has been much lower since 2010.

Pressures from the ageing population, the cost of new drugs and lifestyle factors such as obesity are increasing costs by about 4% a year, but over the past six years the average annual rise has been about 1%.

This has meant the NHS has struggled, despite the protection it has enjoyed compared with other spending departments.

And this period of relative austerity is continuing for the next few years. The budget is set until 2020 - so be prepared for it to get worse for some time yet before it gets better.