How long do we really want to live?

- Published

- comments

Ask people how long they want to live, and many will answer: "As long as I have my health."

But just how old is that? News last week that the limit on human life may be 115 has prompted a great deal of speculation about rising life expectancies.

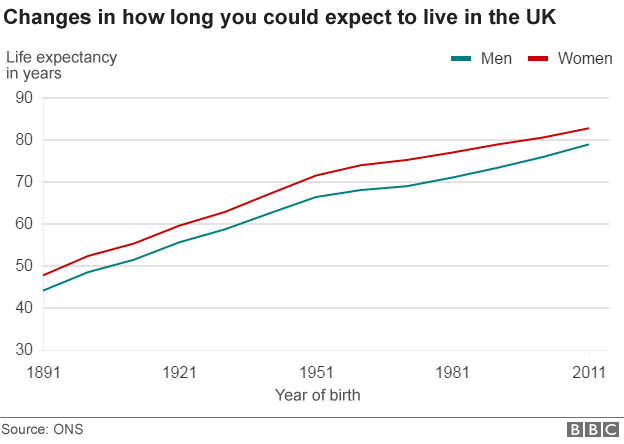

People born today can expect to live almost twice as long as their counterparts in Victorian times.

There are a combination of reasons for this - better diet, safety and medical progress, which has meant people are less likely to die from infectious diseases, strokes and heart attacks.

But the consequence has been that people are increasingly spending their later years struggling with chronic illnesses such as dementia and diabetes.

The result is a surge in interest over what is called healthy life expectancy - a measure of how many years of good health a person can expect.

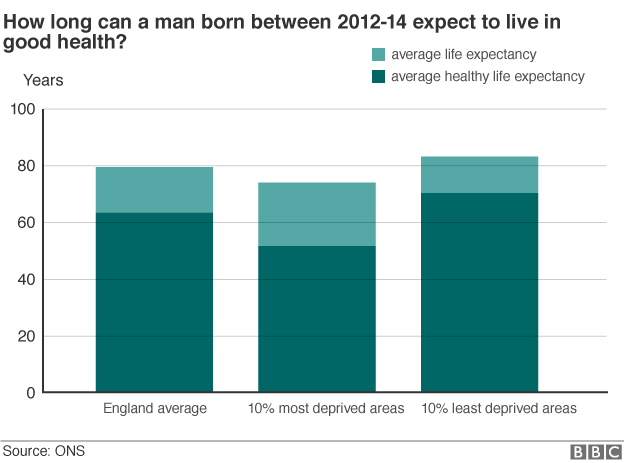

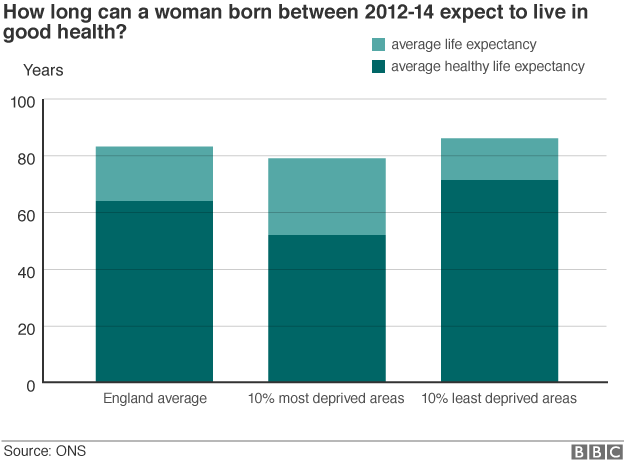

Currently in England the figure is just over 63 years for males born between 2012 and 2014 and 64 for females.

That compares with an overall life expectancy of just shy of 80 and over 83 respectively.

It means for a fifth of our lives we can expect to be struggling with ill health.

But depending on your background, there is a huge variation in when this period of ill health starts and how long it lasts.

For example, males in Wokingham can expect to live over 70 years in good health, while their counterparts in Blackpool only get to the age of 55.

For females, the difference is even greater.

In Richmond upon Thames they can expect to reach 72 - but in Manchester good health ends before the age of 55.

Of course, this has huge ramifications for the individual.

In their new book, The 100-Year Life, academics Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott talk about how those lucky enough to live long lives will have to rethink their approach on everything from money to our relationships.

They describe how the traditional three-stage life that sees people move from education into work and then into retirement is no longer relevant.

Instead, people are younger for longer. The ages from 18 to 30 are being seen as a second-stage of adolescence, where people keep their options open.

Careers are no longer one-dimensional trajectories but will change and renew.

Multi-stage careers will become the norm, where people work hard to put money away and then shift down to something less taxing in their later years, retraining perhaps.

This will be because there will be a need for many, they argue, to keep working as generous final salary pension schemes disappear.

Relationships will change. They will be much longer.

Earlier this month 110-year-old Karam Chand died. He had been married to his wife, Katari, for 90 years - thought to be the longest marriage in the UK.

These longer relationships mean our expectations and approaches to them may have to alter if they are to last.

And how will we look after ourselves when we get older and those years of ill health catch up with us?

The book notes how in some cultures - and in past generations in the UK - older relatives live with their children and grandchildren.

Modern life means that is less common. So how will we pay for care? Will the state be there to help?

This brings us nicely on to why this issue is of huge interest to the government.

It is in the process of raising the retirement age. But if people are not well enough to work, that will do little good to the nation's coffers.

And what will the impact be for the NHS given it is already struggling to cope with the ageing population?

Should the government do more to provide care for people in their old age?

As has been well documented, the opposite is happening at the moment.

When it comes to working out how long you want to live, there is a lot to consider.