Cancer care: Is world class status a distant dream?

- Published

Linear accelerators are wonderful machines. They deliver high-energy radiation to a tumour, helping to destroy cancer cells while sparing the normal tissue which surrounds them.

About four in 10 cancer patients get treated with one. So news that NHS bosses are launching a £130m investment to upgrade or replace half of England's stock in the next two years is understandably being welcomed.

NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens hailed as the "biggest single upgrade" in cancer treatment for the past 15 years that will benefit "hundreds of thousands" of patients.

It is just one of a number of steps NHS England is flagging in the update of the five-year cancer plan on Tuesday.

The strategy was launched in the summer of 2015, promising to create "world class" cancer care by 2020.

Alongside the linear accelerator investment, work has begun on how to ensure cancer patients get earlier diagnosis, which is seen as key to improving survival rates.

This includes piloting multi-disciplinary diagnosis clinics that house a range of specialists and tests under one roof, to try to avoid the delays and inconvenience caused by the practice of passing patients between specialists before they get a diagnosis.

New genetic diagnostic tests have also been made available on the NHS, while experts are developing a new "quality of life indicator" to track care post-treatment.

The £130m investment will help upgrade or replace about half England's stock of linear accelerators

But big questions remain about how achievable the goal set out last year really is.

Cancer survival rates have improved dramatically in recent decades. One in two people diagnosed with cancer today can now expect to survive for 10 years - but that still means 30,000 people are dying early every year because we are not as good as the best.

The challenge the NHS faces - like it does in so many other areas - is how it copes with rising demand.

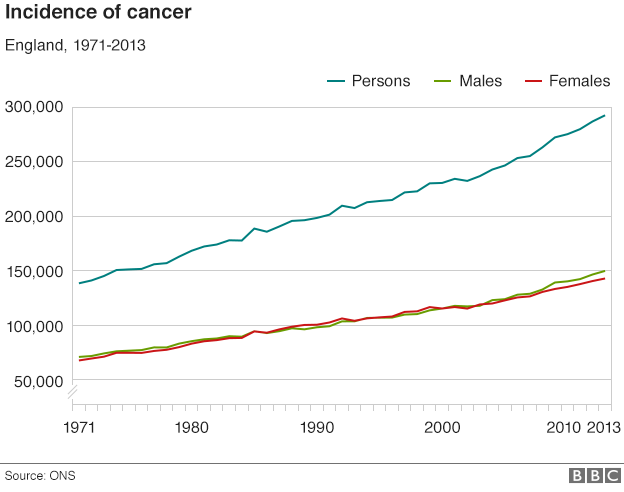

Over the past 40 years, the number of people being diagnosed with the disease has more than doubled, mainly because people are living longer.

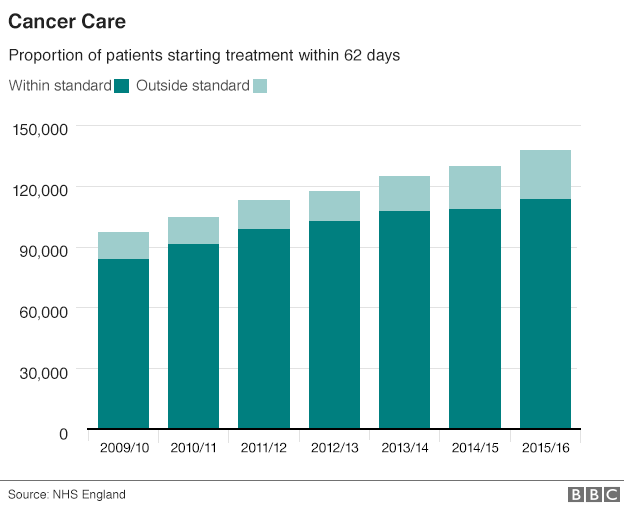

But as money has got tighter, the NHS has struggled to keep up. The major waiting time target for cancer is the 62-day goal for treatment to start following an urgent referral.

The numbers being seen within that timeframe are going up, but so are the numbers that have to wait longer. There are simply too many patients.

Shortages of key health staff, including radiologists and specialists nurses, have also been identified.

Few in the field are confident this is going to change in the foreseeable future - even with the investment being made.

Hence Dr Jeanette Dickson, of the Royal College of Radiologists, said while the funding of the linear accelerators was welcome, "significantly" more money would be needed if services were going to be able to cope with what was being asked of them.

There are other concerns too. Sir Harpal Kumar, the widely-respected chief executive of Cancer Research UK, led the taskforce that drew up the cancer plan.

But this year he was left gobsmacked by the government's child obesity strategy. He said the report, which was criticised for not being tough enough on the food industry, was "inexcusable" given the number of cancers which are linked to lifestyle.

There may be plenty of things for NHS bosses to shout about today, but there is also a lot they should be worrying over too. World class cancer care is still quite some way off.