How do we avoid the antibiotics apocalypse?

- Published

Every year, at least 700,000 people die from drug-resistant infections. It is why government scientists have described antibiotic resistance as one of the greatest global threats of the 21st Century.

So what are people doing to try to avert the so-called antibiotics apocalypse? Well, it turns out, quite a lot.

First, there are those who are trying to get us to take fewer antibiotics. That is because the more antibiotics we all take, the more resistant bacteria become.

Jason Doctor, a psychologist at the University of Southern California, has been carrying out experiments to see whether it is possible to get doctors to prescribe fewer pills, external.

He persuaded more than 200 doctors to sign a letter to their patients, making a commitment to prescribe antibiotics more judiciously. They blew it up into the size of a poster and put it on the walls of their health clinics.

Then they experimented with a ranking system, sending doctors a monthly email telling them how many antibiotics they were prescribing inappropriately compared to their peers.

They set up alerts on doctors' computers, prompting them to question whether they really needed to prescribe antibiotics and they also found ways that doctors could appease persistent patients who demanded the medication.

When they tried all these different approaches together, it dramatically reduced the number of antibiotic prescriptions issued.

Some of these changes are now being implemented across the US and in other countries, but even if people were only given antibiotics when they really needed them, that would not solve the problem. Because while humans are a big market for antibiotics, there is an even bigger one.

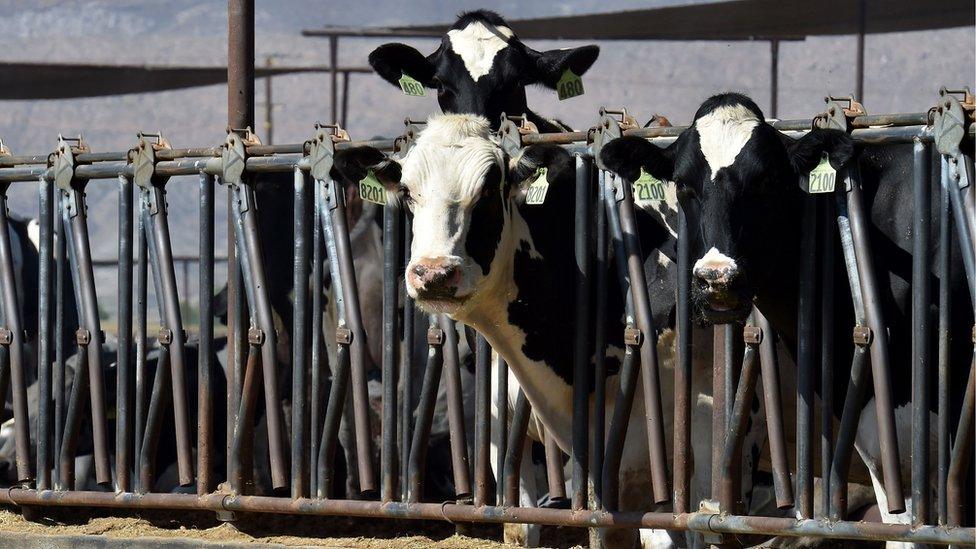

In 1950, a chance discovery in a laboratory showed that antibiotics make animals grow faster. Since then, farmers all over the world have pumped them into their animals, even after scientific studies proved that bacterial resistance could pass from animals to humans.

But one country has shown that farmers who were once dependent on antibiotics can wean themselves and their animals off them.

Bacterial resistance has been spread through the food chain

The Netherlands has more animals per square metre than any other country on the planet and for years, those animals were routinely fed antibiotics. A ban on giving growth-promoting antibiotics to their animals had little effect as farmers used the same amount and just labelled them differently.

But after a series of health scares, the government decided to crack down. In 2009, farmers were told they had to reduce the amount of antibiotics they were giving their animals by 20% in two years and 50% in five.

Dik Mevius is an infectious disease specialist and vet who helped farmers draw up a plan to meet those targets.

They set up a database, revealing which farmers were the worst offenders, and stopped farmers from shopping round for antibiotics from different vets. Any vets or farmers who prescribed or used antibiotics unnecessarily were fined or lost their accreditation.

And, surprisingly, Dutch farmers got on board. They stopped using so many antibiotics, which, for many of them, meant they had to change the way they reared their animals.

"It really was a revolution," says Mr Mevius. "We reduced the amount of antibiotics used by 60% in just a couple of years."

But most countries are going in the opposite direction. It is thought that China, Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa will all double their use of antibiotics by 2030 and so resistance will spread. That is why some scientists are scouring the world, looking in the oceans, rainforests and deserts for new sources of antibiotics.

Could the saliva of the Komodo dragon help in devising a new kind of antibiotic?

Researchers recently went to Panama and took samples from the algae-filled fur of a three-toed sloth. Others have been looking for new antibiotics in the saliva of Komodo dragons, although it is too early to tell yet whether they have been successful.

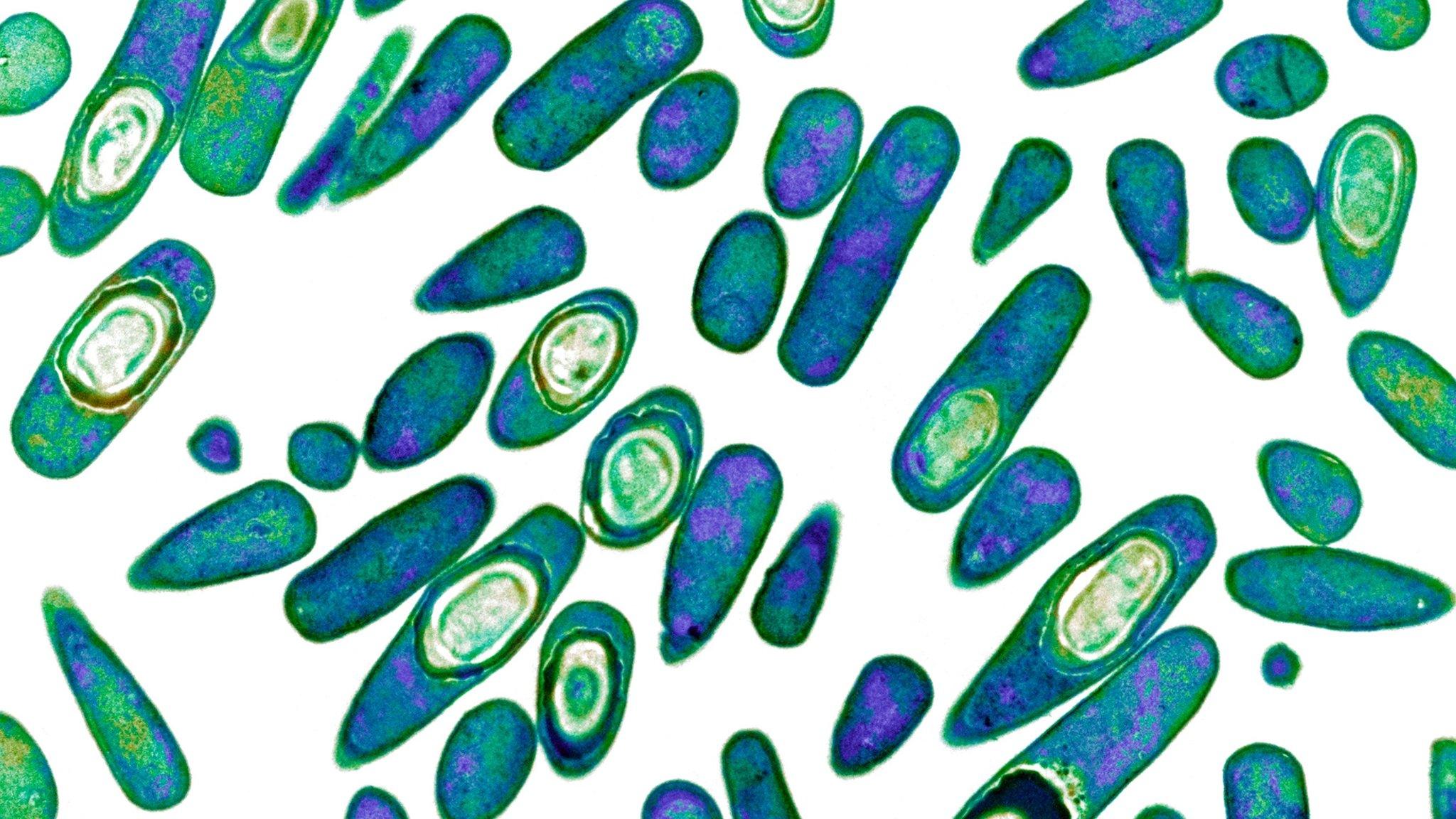

Then there are those scientists who are not looking for new antibiotics but who are taking the fight to the bacteria themselves. Kim Hardie is a microbiologist at Nottingham University who studies the way that bacteria communicate. Yes, bacteria communicate.

When a single bacterium arrives in your lungs, it hides from your immune system and from the antibodies already within you that might kill it. So it does not reveal its weapons - its toxins - but sits there, waiting.

"Once it realises it's a good place to multiply, then it communicates," she says. Separate bacteria count each other, until they sense there are enough. Then they draw their weapons and attack the immune system.

"If you have a single soldier against a castle, it won't do much to that castle," she says. "But if it waits for the rest of the army to arrive and they deploy their weapons at the same time, they can overcome the castle."

What, then, if you could stop bacteria communicating, so that even though you may have harmful bacteria in your lungs, they cannot count each other and so never launch an attack? Ms Hardie says it can be done and experiments in the laboratory have had good results. She thinks an antibiotic based on this principle could arrive on the market in around 10 years.

There are many other experiments and projects going on too. Success will largely depend on us learning much more about bacteria.

As they say in battle, know your enemy. So how do we avert the antibiotics apocalypse? We learn to outsmart bacteria.

The Inquiry: How did we mess up antibiotics? and The Inquiry: How do we fix antibiotics? were broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can listen to the programmes online now, or download the programme podcast.

- Published18 October 2016

- Published12 August 2016

- Published28 July 2016

- Published25 May 2016

- Published19 May 2016