Ambulance pressure: Five ways services are innovating

- Published

Ambulance services across the UK are facing growing pressures. Demand is increasing, and they are struggling to hit their targets to respond to life-threatening emergency calls.

Around the NHS, ambulance bosses are looking at new and innovative ways to deliver the vital emergency service. Some are pretty radical and wide-ranging, others are small-scale.

But all have one ambition: to ensure those at most risk get a response as quickly as possible.

Treat fewer patients as emergencies

Wales, like the rest of the UK, was struggling to respond to life-threatening calls within the eight-minute target.

So, in October 2015, it narrowed its definition "life-threatening" to cover only:

cases where imminent death is possible - such as cardiac arrest, serious road accidents or where the patient is not breathing

emergencies involving vulnerable patients such as pregnant women and young children

Patients with chest pains, the symptoms of stroke or serious fractures can no longer expect to be reached within eight minutes

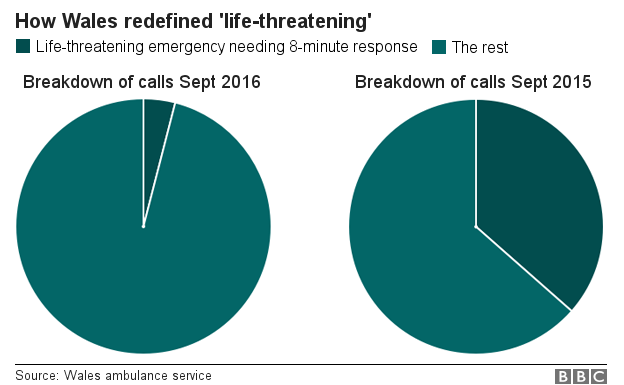

The move has seen nearly a 90% reduction in the number of calls needing an eight-minute response.

In September last year, more than 13,000 calls a month were deemed to be in need of an eight-minute response. This September, just over 1,400 were.

It means the service is now responding to close to 80% of its highest priority calls in eight minutes, compared with under 50% a year ago.

The Welsh ambulance service says it has been monitoring the impact on those patients no longer getting an eight-minute response and does not have concerns.

Give call handlers longer to assess calls

In England, ambulance services have been trying out giving call handlers longer to assess calls.

Traditionally they have been given 60 seconds to triage an emergency call before they have to dispatch an ambulance - unless they think life is in imminent danger, when they have to send a crew straight away, known as red one.

If the 60 seconds elapses before they can decide if it requires an emergency eight-minute response, they have to dispatch.

This has been causing problems.

In about a fifth of cases, a crew is called back before it reaches the scene, after it becomes apparent an emergency response is not needed.

So since early 2015, ambulance trusts - with the agreement of NHS England - have been piloting giving control centres extra time - between 180 to 300 seconds.

In the end, six of the 10 ambulance trusts were taking part, and this year it was decided 240 seconds was the optimum time for making a judgement, so all trusts started using that from October.

A review of the pilot found it had ensured there were more likely to be crews available to answer calls and red-two response times had improved by between 2.5% and 2.9%, while there were "no patient safety issues".

Deploying paramedics to manage queues

As the BBC investigation has uncovered, the queues ambulances face when they take patients to accident and emergency units are causing problems.

They are meant to be able to hand over patients within 15 minutes, but this does not always happen.

The number of delays has risen by 52% over the past two years.

The West Midlands ambulance service is one of the few that looks like it has got a handle on this - the number of delays being experienced is pretty stable compared with other areas.

Part of the reason is that the trust has been working with local hospitals to deploy paramedics outside A&E.

Their job is to take on patients that ambulance crews bring in, to allow the ambulances to get back on the road as quickly as possible.

These positions - known as Halos (hospital ambulance liaison officers) - are being funded at all the major A&Es in the region.

Similar schemes are in place in other areas as the NHS tries to get on top of the delays.

Tackling timewasters and hoax calls

Timewasters and hoax calls are two of the big frustrations for hard-pressed ambulance services.

But the Braunstone Blues project in Leicester shows how these problems can be tackled.

The scheme - a partnership between the local police, ambulance service and fire service - is targeted at the estate in the city that makes the highest number of 999 calls.

A team has been employed to offer free 30-minute home visits about how to keep "healthy, safe and secure".

Help with loneliness, anxiety, depression and dealing with antisocial behaviour is also provided, along with information about other organisations that may be able to provide support.

The scheme is still in its early days, but there are already signs it has started reducing callouts.

Working with mental health patients

A mental health triage team has been launched in Bedfordshire to help reduce admissions to hospital and relieve the pressure on the ambulance service.

The scheme is a partnership between the East of England ambulance service, Bedfordshire Police and local NHS bosses.

The team is made up of a paramedic, police officer and mental health professional responding to mental health calls across Bedfordshire 365 days a year working from 15:00 to 01:00.

They attend incidents, together in one car, where there is an immediate threat to life - someone threatening to self-harm for example - or where someone has called 999 saying they are concerned for a member of the public.

The team has a dedicated phone line and can be called to incidents by the police and ambulance control rooms.

The pilot runs until next July and is aimed at making sure people going through a mental health crisis are given the right care.