Hopes for new Alzheimer's drug dashed

- Published

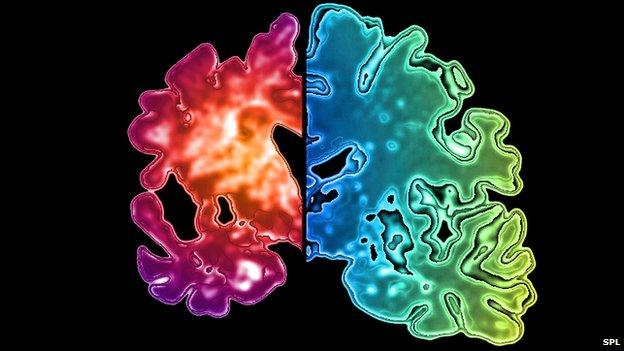

Loss of tissue in a demented brain compared with a healthy one

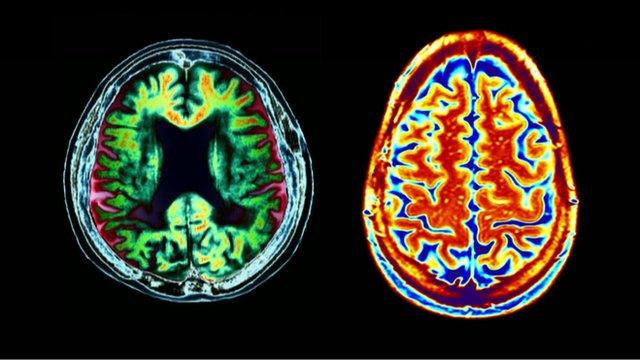

A major trial of a drug to treat mild dementia due to Alzheimer's disease has ended in failure.

Patients on solanezumab did not show any slowing in cognitive decline compared to those treated with a placebo, or dummy drug.

The results of the trial were much anticipated after promising data was released last year.

The phase 3 trial, called EXPEDITION3, involved more than 2,000 patients with Alzheimer's disease.

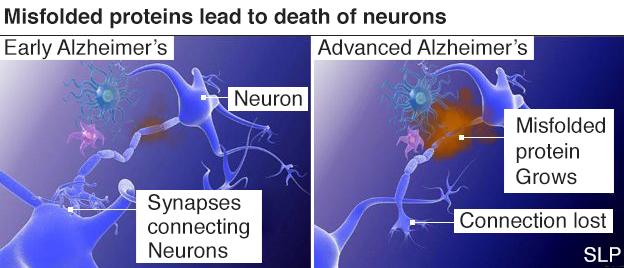

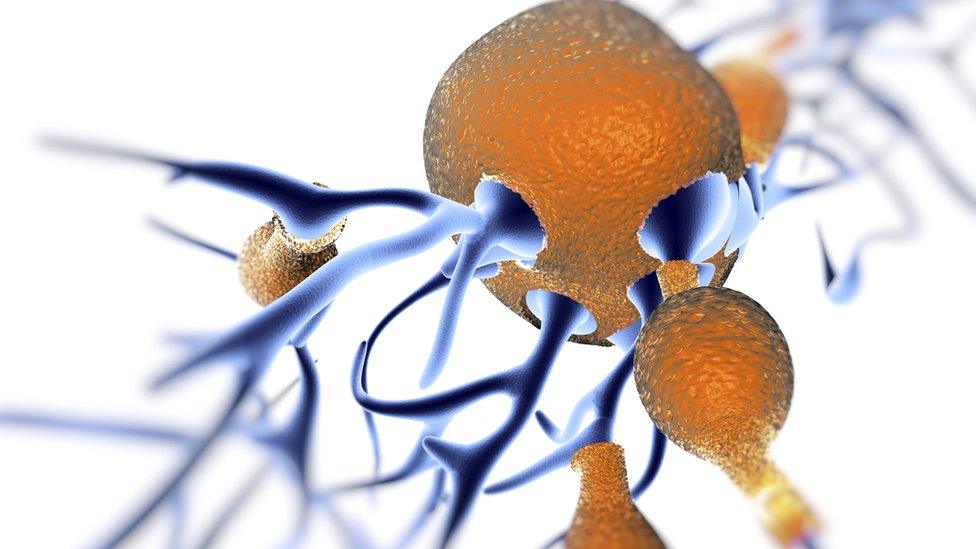

The drug targeted the build up of amyloid protein, which forms sticky plaques in the brain of patients with Alzheimer's.

It is thought the formation of these plaques between nerve cells, known as neurons, leads to damage and eventually brain cell death.

Dementia now leading cause of death

How close are we to stopping Alzheimer's?

There are several amyloid-clearance drugs going through trials, but solanezumab was at the most advanced stage of development.

These results were the last major hurdle before Eli Lilly could seek to get the drug licenced, which will not now happen.

John Lechleiter, chief executive of Eli Lilly, said: "The results of the solanezumab EXPEDITION3 trial were not what we had hoped for and we are disappointed for the millions of people waiting for a potential disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer's disease."

Lilly estimates it has invested $3bn in dementia research in the past 25 years.

Prof Nick Fox, director of the Dementia Research Centre, UCL said: "This is a setback and it is very disappointing but there are other experimental approaches going through trials which show much greater promise than solanezumab."

Prof Peter Roberts, an expert in pharmacology at University of Bristol, said he was not surprised by the findings.

He said: "The problem, to my mind, is completely fundamental. There is still no convincing evidence that shows a clear relationship between amyloid deposition and deficits in cognition in humans.

"All we really know is that evidence of amyloid deposition begins up to maybe 20 years before the onset of Alzheimer's disease."

Prof Roxana O'Carare, Professor of Clinical Neuroanatomy, University of Southampton, said part of the problem might be that amyloid had to be removed from the brain, not just broken down.

"The brain is not equipped with lymph vessels as other organs have. Instead fluid and waste are eliminated from the brain along very narrow pathways that are embedded within the walls of blood vessels.

"These pathways change in composition and fail in their function with increasing age and with the risk factors for Alzheimer's disease, resulting in the build up of amyloid in the walls of blood vessels.

"When a vaccine such as solanezumab is administered, the sticky plaques of amyloid from the brain break down, but the excess waste and fluid is unable to drain along the already compromised drainage pathways."

Jeremy Hughes, chief executive of Alzheimer's Society, said they had high hopes for the drug, which have been dashed.

"It's extremely disappointing to learn that it hasn't delivered a meaningful change for people living with dementia, when the need is clearly so great.

"Dementia is society's biggest health challenge - and we've seen time and again that developing effective treatments is incredibly difficult."

But he added: "This is only one drug of several in the pipeline and they aim to tackle dementia in different ways, so we should not lose hope.

"Dementia can and will be beaten."

Follow Fergus on Twitter, external

- Published31 August 2016

- Published27 July 2016

- Published23 July 2015

- Published22 July 2015