'No solid evidence' for IVF add-on success

- Published

Nearly all costly add-on treatments offered by UK fertility clinics to increase the chance of a birth through IVF are not supported by high-quality evidence proving that they work, a study has revealed.

The findings are the result of research commissioned by BBC Panorama and conducted by Oxford University's Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, world experts in assessing medical studies.

On average, only one in four cycles of IVF (in vitro fertilisation) across all age groups results in a live birth.

Many clinics offer add-ons, treatments on top of standard IVF, in an attempt to boost the chances of having a baby.

'Shocked'

The Oxford team spent a year searching for every claim made about each treatment available at UK clinics and researched more than 70 websites - identifying 27 treatments that are considered to be add-ons.

However, its research found that 26 of them were not backed up by good scientific evidence of success.

Jessica Hepburn spent thousands of pounds on eleven cycles of IVF including add-ons without success

The treatments include genetic screening tests, additional drugs, blood tests to measure the immune system and special devices to house an embryo. They can cost from £100 up to £3,500 each on top of the costs of IVF.

Prof Carl Heneghan, director of the centre and who led the team, was shocked and told Panorama: "It was one of the worst examples I've ever seen in healthcare.

"The first thing you would expect to happen is that anything that makes a claim for an intervention would be backed up by some evidence.

"Some of these treatments are of no benefit to you whatsoever and some of them are harmful."

Only one treatment, called an endometrial scratch, was supported by moderate quality evidence it would help. It involves a procedure to scratch the womb lining to help an embryo successfully implant, although the evidence for this treatment was not itself beyond doubt.

The conclusions of the study are published in the medical journal The BMJ.

Patients the BBC spoke to had tried many of these add-ons in their desperation to have a baby, spending tens of thousands of pounds in the process.

Jessica Hepburn spent over £70,000 on eleven cycles of IVF and had many different "add-ons". She never had a baby.

She now campaigns for patients to receive better information about fertility issues.

"These are doctors. We believe what doctors tell us and this is a doctor that holds my happiness in his hands," she said.

Long-standing industry critic and fertility pioneer Professor Robert Winston told Panorama that he thinks most add-ons are unnecessary.

"So many of them are not justified," he said.

"They think they're giving the patient hope and in my view that's completely the wrong way to do this, you need to give the patient a treatment which is reliable."

One in four IVF attempts result in a baby

At the heart of the debate is whether patients should be charged large sums of money for treatments that have not been demonstrated to improve their chances of having a baby.

Adam Balen, chairman of the British Fertility Society, told Panorama: "Provided we're not causing harm, I don't think that there's any problem with giving patients information... discussing that we don't know yet but there is an evidence base developing."

In Birmingham, one fertility clinic Panorama spoke to doesn't offer many add-ons to their NHS or private patients because of the lack of evidence behind them.

Dr Sue Avery, director of the Birmingham Women's Hospital, told us: "I think for many patients the feeling is, well, whatever I can have as long as it's not going to be harmful, I want to have it.

"Our feeling here is that if you feel that that's absolutely essential for you then unfortunately you will need to go elsewhere. It's going to be a cost to you and we can't honestly say you should have this because there's no evidence to support it."

Panorama found evidence that, when marketing one add-on, not all clinics were telling patients everything they needed to know.

The add-on is called preimplantation genetic screening, which screens embryos for abnormalities that might stop them developing further.

A trial in 2007 discovered that an earlier version of this test could actually reduce the chances of having a baby.

Many clinics now offer more accurate versions of the screening. But as yet there is no high quality evidence from robust trials that these new versions improve the odds of becoming pregnant.

Randomised trials are currently under way.

But a number of UK clinics already sell it for up to £3,500 and Panorama found not all were up front with us about the lack of evidence in their marketing pitches.

We approached a range of staff from 18 British and foreign clinics at random at a fertility fair, saying we had not had IVF before but were interested to know whether PGS would be a good add-on treatment.

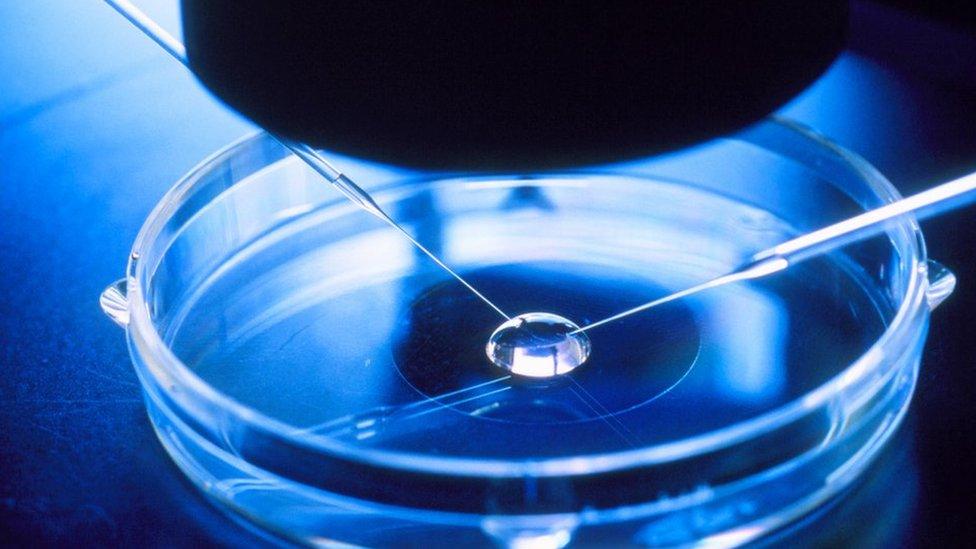

Genetic screening in the lab - but will it enhance the chance of success?

Five clinics we spoke to were positive about the treatment.

Eight told us they would only offer it to women over the age of 40 or those who had experienced repeated IVF failures, despite the lack of strong evidence to prove it increases their chances of having a baby.

Five clinics told us they would not recommend PGS, because of the lack of good enough evidence.

Sebastiaan Mastenbroek is a clinical embryologist from the University of Amsterdam, whose trial on the first version of PGS showed it could lower birth rates.

He told us he was surprised PGS was being offered in routine practice again before the completion of randomised trials which are still under way.

So are patients being adequately protected?

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority is the UK's fertility clinic regulator.

A spokesman for the HFEA told Panorama that it was "concerned about the recent step change in the use of treatment add-ons".

But, he added, the regulator had "limited powers to stop clinics offering them, or to control pricing". He said the HFEA published information directly for patients so they could have the facts before they went to a clinic.

Lord Winston says we need evidence-based medicine

The authority said it planned to launch a new website next year with more information about a wider range of add-ons.

Panorama found many patients are still willing to pay for unproven treatments, even when their clinics tell them there is no high quality evidence behind them.

One patient told the programme: "I think if someone said if you cut off your hand you'll have a baby, I think I would have done it."

Panorama: Inside Britain's Fertility Business is broadcast on BBC One at 20:30 on Monday November 28 (except Wales) and will be available on the BBC iPlayer afterwards.

What is IVF?

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is one of several techniques available to help couples with fertility problems have a baby.

During IVF, an egg is removed from the woman's ovaries and fertilised with sperm in a laboratory.

The fertilised egg, called an embryo, is then returned to the woman's womb to grow and develop.

It can be carried out using a woman's eggs and a man's sperm, or eggs and/or sperm from donors.