Teaching primary school children about mental health

- Published

A new scheme teaches children about mental health through fun games and workbooks

The mental health of children is a rising area of concern and one which schools are trying to combat. Emma Jane Kirby reports from south London about a scheme that involves teaching primary schoolchildren about mental health through fun games and workbooks.

The children are half out of their chairs, hands straining in the air, knees jiggling with excitement as they beg to be picked.

The smiling lady at the front of the class repeats her question.

"Can I see your thoughts? Can I smell them or touch them?" she asks.

Managing moods

Dr Anna Redfern is clearly a gifted communicator as well as a clinical psychologist. It is not everyone who can persuade a class of eight- and nine-year-olds to talk about their innermost feelings in front of each other.

Yet here are the children of Class 4S at the Oliver Goldsmith Primary School, Peckham, south-east London, openly admitting that they have days when they feel down or angry or just very sad.

"No-one can see our thoughts," says a little girl confidently. "And that's why we need to talk about them."

Dr Redfern and her colleague Dr Debbie Plant are delivering a new programme called Cues-Ed, external, funded by the South London and Maudsley Trust.

The programme teaches children to recognise the signs when things aren't right, and some behavioural techniques to help them manage low mood.

"We all have feelings," says Dr Redfern.

"And we will all have difficulties in our lives which will make us feel and think things that are very challenging.

"And rather than being fearful about talking about these things, we want children to have the language that allows them to get the right help and to say, 'Actually this is how I am feeling, these are the things I am thinking and I need some extra support.'"

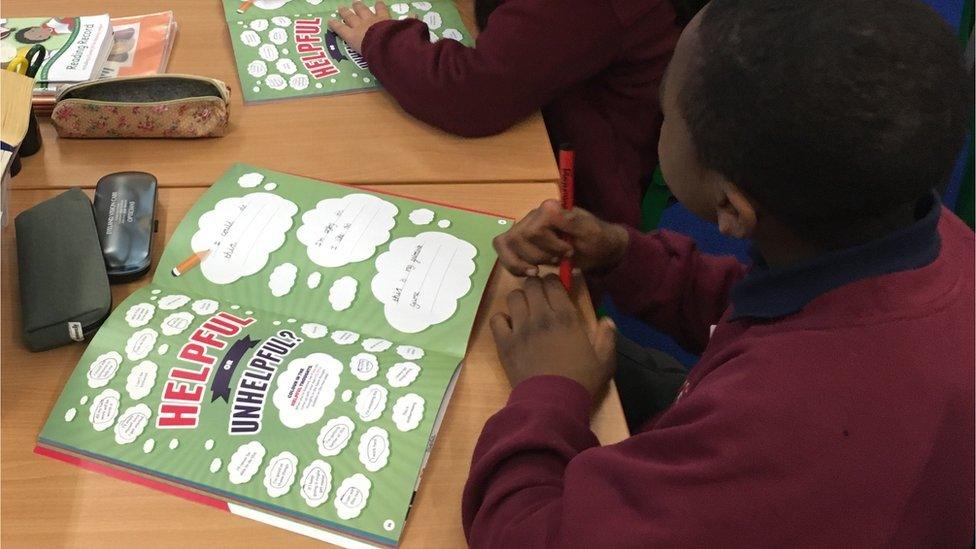

For one exercise, children separate helpful and unhelpful thoughts written on pieces of paper

In today's lesson the children are looking at the difference between helpful and unhelpful thoughts.

Specially designed cartoon characters help the children relate to how different situations might make them feel - all the children sympathise when one of the cartoon characters is feeling left out and imagines that his friends are laughing at him.

'We should be worried'

The whole programme is carefully couched in fun and child-friendly terms. Adult words such as "depression" are never used.

"Do you ever have one of those really bad days when everything seems to be against you," asks Dr Redfern with a big smile. "Like when you go downstairs for breakfast and there are no more Coco Pops, there's only Weetabix?"

The class groans in horror, and the children start chatting to each other about their own bad days.

According to the Association of School and College Leaders, external, 65% of head teachers say they struggle to get mental health services for pupils.

Over three-quarters of teachers surveyed said they had seen an increase in self-harm or suicidal thoughts among students.

Yet, at the moment, Cues-Ed is available only in south London and generally has to be funded by the participating schools themselves. A package of classes costs £3,950.

As she helps a child with his workbook, Dr Plant, whose team leads the project, says it is vital that children get mental health education early and all together.

She would like to see the programme rolled out nationwide.

"I think we should be worried about young people's mental health," she tells me.

"The last time the government took statistics it showed one in every 10 children suffered a mental health difficulty - that's three in every class."

'Believe in yourself'

We watch her colleague calming a little boy who's got himself worked up because he doesn't think he can do the writing exercise he's been tasked with.

The child next to him offers some positive advice.

"If you're upset, you could try meditation or breathing deeply," she says. "And you should believe in yourself."

Dr Plant smiles as we watch them, happy to see last week's lesson on positive thinking has sunk in.

"You know, we worked in adolescent mental health for so long," she says "And we thought we were doing so well. But the young people said to us, 'Why didn't you teach us all of this when we were seven, eight and nine? That would have really made a difference.'"

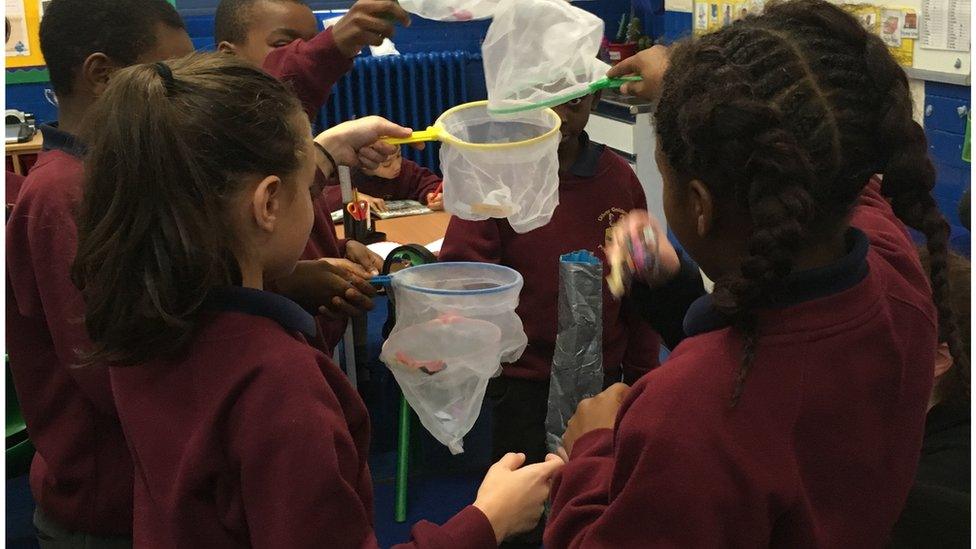

The children fish for helpful and unhelpful thoughts on pieces of paper blown around the classroom

The children are extremely excited now as they're handed fishing nets and told to catch little pieces of coloured paper on which are written helpful and unhelpful thoughts and which are being blown across the classroom.

The class teacher, Sophia Campbell-Whitfield, selects a little boy to pass round the class with a bin. I ask him what he's doing.

"Putting all the unhelpful thoughts in the bin," he says, "because they're rubbish."

'Big changes'

There is no doubt the children are all engaged in the lesson, but does it make any practical difference to their behaviour? Mrs Campbell-Whitfield nods emphatically.

"Definitely," she says. "This class had a lot of issues last year - but now with the Cues-Ed programme, I have seen some big changes.

"I see children use strategies to calm themselves, whereas before they would have stormed off… and they now have a proper conversation with each other about behaviour and sometimes they even say, 'Come on now, did you catch that thought?'"

One nine-year-old boy appears emotionally very fluent as he tells me how he gets very angry and sad when he is told off at school.

But he remembers what he has been taught in Cues-Ed about trying to dispel his low mood and unhelpful thoughts by doing something he finds fun and likes doing.

I ask him what that is in his case, and he doesn't hesitate.

"I like to enjoy my lunch."

- Published29 November 2016

- Published29 November 2016

- Published27 November 2016

- Published29 November 2016