NHS screening plan for type 2 diabetes 'inaccurate'

- Published

- comments

The NHS programme for screening those at high risk of type 2 diabetes is unlikely to have much impact, an Oxford University study in the BMJ suggests.

It concluded that inaccurate blood tests would give too many people an incorrect diagnosis, while lifestyle changes had a low success rate.

But the director of the NHS programme said its approach was based on "robust evidence".

The programme started last year and will cover all of England by 2020.

Type 2 diabetes leads to 22,000 early deaths every year in England and costs the NHS £8bn.

In the UK, about 3.2 million people have type 2 diabetes and this is predicted to rise to 5 million by 2025.

The UK's National Diabetes Prevention Programme, external, which aims to identify thousands of people at high risk of developing the condition each year, follows a "screen and treat" approach.

This involves a screening test for pre-diabetes, then tailored treatment or advice on diet and lifestyle to prevent the disease developing.

'Falsely reassured'

But after analysing the results of 49 studies of screening tests and 50 intervention trials, University of Oxford researchers said the policy would benefit some, but not all those at high risk.

They also said a population-wide approach to diabetes prevention would be a useful addition.

In the BMJ study, external, they found that two blood tests - HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose - were inaccurate at detecting pre-diabetes, although they are the only ones available to doctors and patients.

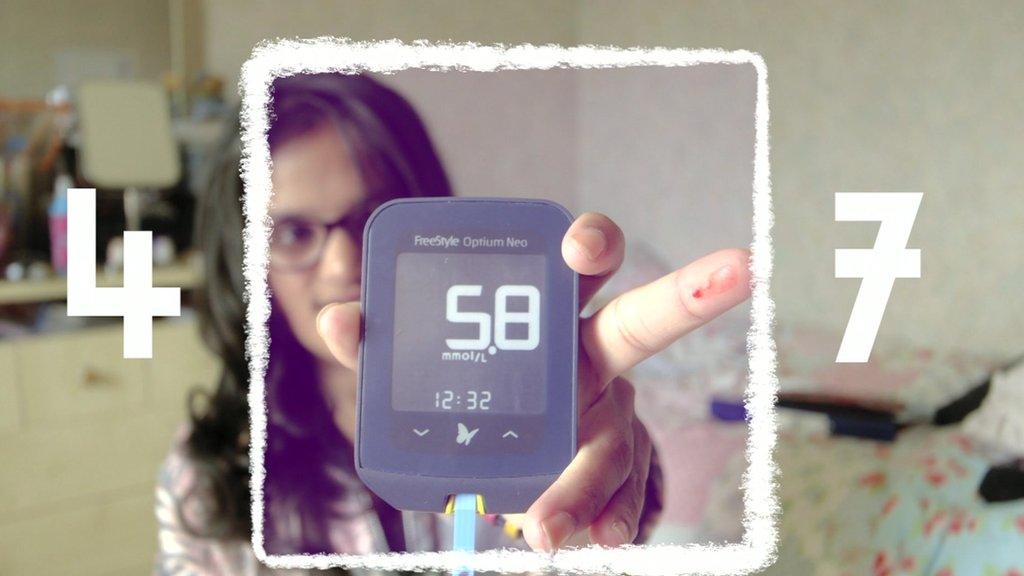

Weight control is part of the lifestyle advice given to those at high risk of type 2 diabetes

They also found that lifestyle interventions lasting three to six years showed a 37% reduction in relative risk of type 2 diabetes - equivalent to 90 fewer people in every 1,000 developing the disease.

When treated with a drug that helps lower blood sugar levels, 80 fewer participants out of 1,000 developed diabetes compared with those not taking the drug.

The authors concluded: "As screening is inaccurate, many people will receive an incorrect diagnosis and be referred on for interventions while others will be falsely reassured and not offered the intervention.

"These findings suggest that 'screen and treat' policies alone are unlikely to have substantial impact on the worsening epidemic of Type 2 diabetes."

'Active culture'

However, Matt Fagg, programme director for the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme, said it was "a key part of the solution" and was "based on a comprehensive collation of robust evidence".

He added: "Diabetes prevention also needs to start even earlier - we're committed to reducing obesity and creating a more active culture so that we see fewer people at risk in the first place."

And Jonathan Valabhji, national clinical director for obesity and diabetes for NHS England, said the NHS programme was not a screening programme -"it empowers people who have already been identified through routine clinical practice to reduce their risk".

"As this BMJ paper highlights, such lifestyle interventions have been clearly shown to work.

"The NHS is not willing to sit idly by while these individuals progress to Type 2 diabetes," he said.

Prof Norman Waugh from Warwick Medical School said there was a balance to be struck between screening and treating individuals, and the public health model of changing behaviour in the whole population at risk.

Public health measures could include helping people to control their weight, introducing taxes on food and drinks and making physical activity more accessible.

He said: "Preventing or delaying type 2 diabetes requires effective measures to motivate the general population to protect their own health."

- Published2 October 2016