Is it time for embryo research rules to be changed?

- Published

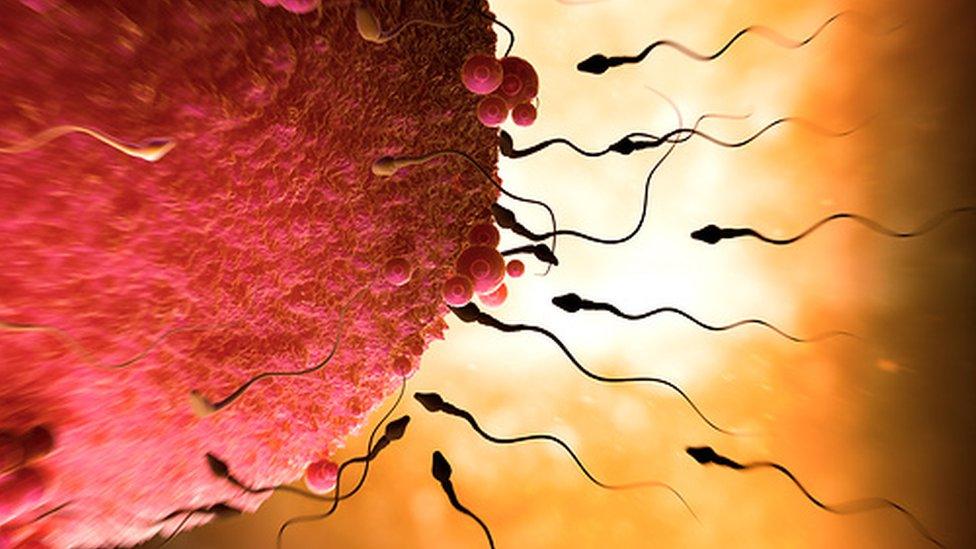

Experts are renewing calls to allow experiments on embryos beyond 14 days of development, saying it would drive medical breakthroughs.

Research on human embryos can only happen under a licence in the UK and it is currently illegal to keep them alive in laboratories for more than two weeks after fertilisation.

Until recently, this cut-off was almost irrelevant in terms of viability since science had not found a way to physically support life in the lab beyond about a week.

But researchers have found a way to chemically mimic the womb which would allow an early stage embryo to continue to develop for longer - at least 13 days after fertilisation, but potentially much more.

One of the pioneers of IVF is calling for a government inquiry.

Prof Simon Fishel was on the team involved with the birth of the world's first IVF baby. He believes that moving the limit to 28 days would be good for furthering scientific understanding.

Simon Fishel founded the CARE fertility group in Nottingham

Prof Fishel, who founded the CARE Fertility Group, said: "I believe the benefits we will gain by eventually moving forwards when the case is proven will be of enormous importance to human health."

Observing how the embryo changes over weeks could shed light on why some early miscarriages occur, he says.

Embryos normally implant in the wall of the uterus at around day seven and still resemble a ball of cells at that stage.

It takes weeks of rapid cell division and growth before it begins to resemble something more baby-like, with a beating heart, developing eyes and budding limbs.

Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz has developed a technique that could, theoretically, allow embryos to survive for longer in the lab than the current legal limit of 14 days.

The Cambridge University professor says: "We know that a lot of pregnancies fail on the time of implantation which is day seven. So now we can identify events which are not happening correctly and how in future we can help them occur normally."

But there are many who are concerned about extending the legal limit.

Prof Fishel said: "There are some religious groups that will be fundamentally against IVF, let alone IVF research in any circumstances, and we have to respect their views."

The 14-day rule was first suggested in the UK in 1984. With the advent of IVF, a committee, chaired by Mary Warnock, was set up to look at the ethics and regulation of this new technology.

It concluded that the human embryo should be protected, but that research on embryos and IVF would be permissible, given appropriate safeguards.

Setting a cut-off was tricky. For example, should it be based on when an embryo develops a nervous system that might begin to detect pain? At the time, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists suggested 17 days as a limit - the point at which early neural development begins.

The Warnock report, external settled on 14 days - when the embryo is a distinct individual and can no longer form a twin.

That recommendation is now decades old. Some say it should be reviewed.

David Jones, founder of the Centre of Bioethics and Emerging Technologies, is against changing the limit.

"It would be a stepping stone to the culturing of embryos and even foetuses outside the womb. You are really beyond the stage when the embryo would otherwise implant and that is a step towards to creating womb like environment outside. People will then ask why can't we shift it beyond 28 days?"

A recent YouGov poll of 1,740, commissioned by the BBC, found that 48% of the UK general public supported increasing the limit up to 28 days, 19% wanted to keep the present limit of 14 days and 10% wanted a total ban.

But one in four of those questioned said they did not know, suggesting some may need more information to reach an informed opinion.

BBC Radio 4's two-part documentary 'Revisiting the 14 day rule' starts on Tuesday 17 January at 11:00 GMT.

- Published13 September 2016