Q&A: Acrylamide - a reason to give up browned toast and roast potatoes?

- Published

Roast potatoes with roast chicken - a thing of the past?

Advice on how to reduce the amount of acrylamide in our diets has been issued by the government's food safety body, because the chemical could cause cancer.

Acrylamide is created when starchy foods are roasted, grilled or fried for long periods at high temperatures.

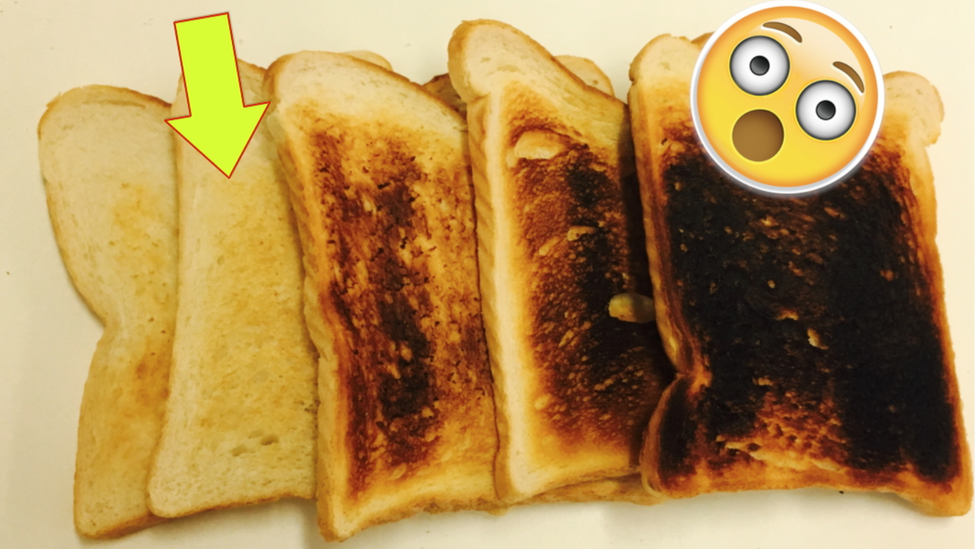

The message is to cut back on browned and burnt toast, cook roast potatoes, chips and parsnips carefully - to a golden yellow colour - and eat fewer crisps, cakes and biscuits.

Are they trying to take all the fun out of life?

We try to put the latest dietary advice from the Food Standards Agency (FSA) into perspective.

Should I stop eating roast potatoes?

Do not panic - you do not need to give up on the delicious Sunday roast staple just yet.

Crispy, brown roast potatoes which are traditionally cooked at very high temperatures do produce acrylamide, but the key is to try to cook them to the right colour.

"Go for gold" is what the FSA advises - that is a golden yellow colour, rather than brown.

And that applies to parsnips and all types of potato products too.

So if you are a roast potato fanatic you might want to rein in your obsession and cook them a little less often.

If you love them at Christmas and special occasions in-between, then try turning down the oven heat and taking the roast potatoes out before they start to turn excessively crispy and brown.

Won't that change the taste?

Well, during the browning process, when starchy foods are heated they do give off new flavours and aromas.

The bad news is that the same process also produces acrylamide, so there may have to be some trade-off between tastiness and the colour of your food.

When cooking packaged products, such as oven chips, follow the instructions carefully - they are designed to ensure you are not cooking starchy foods for too long or at too high a temperature.

Boiling, steaming or microwaving food is a much better and healthier option.

Five shades of toast: go for a golden yellow colour, say government food scientists

If I burn toast, is it OK to scrape off the burnt bits?

There is no need to worry about the occasional slightly overcooked piece of toast or other food.

Scraping off the dark brown bits of toast might help reduce acrylamide content a bit - and it certainly will not increase it.

But, in general, aim for a golden or lighter colour (see above).

How much of a risk is acrylamide?

Studies in animals found that the chemical causes tumours. This suggests that it also has the potential to cause cancer in humans.

The FSA has used that data and multiple dietary surveys to work out whether an average person's exposure to acrylamide in food is a concern.

Scientists believe that there should be a margin of exposure of 10,000 or higher between an average adult's intake of acrylamide and the lowest dose which could cause adverse effects.

But at the moment the numbers are 425 for the average adult and 50 for the highest consuming toddlers, making it a slight public health concern, UK and European food safety experts say.

However, Cambridge University risk expert Prof David Spiegelhalter is unconvinced by this very strict safety standard.

He says the margin of exposure figure is "arbitrary" and 33 times higher than the current margin for average adults in the UK, and he questions whether a public campaign should be launched on that basis.

Where does it rank alongside other risk factors for cancer?

Stopping smoking is the most important thing you can do to prevent cancer.

Keeping a healthy bodyweight and eating a balanced diet ranks second.

Our individual risk of cancer depends on a combination of genes, our environment and the lifestyle we lead, which we are able to control.

The amount of acrylamide in our diets is one small element of our food intake which we can control to help reduce our risk of cancer during the whole of our lives.

Research has shown that eating too much processed meat and red meat can increase the risk of developing cancer - that is a definite.

Cooking meat at high temperatures such as grilling or barbecuing can produce cancer-causing chemicals called heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic amines (PCAs).

This advice is another good reason to cut back on chips and eat a healthy, balanced diet

What is the food industry doing to help?

The FSA says the industry is doing its bit to find out how to reduce levels of acrylamide in food.

A toolkit and brochures have been produced for food manufacturers and food businesses, giving information and advice.

Evidence suggests the industry has been lowering levels of acrylamide in food over the past few years.

But there are currently no rules on the maximum limits for the chemical in food.

Is the FSA worrying people unnecessarily with this advice?

It is their job to make sure the food we eat is safe and to let the public know if they are concerned about any risk to our health.

This is not a new risk - people are likely to have been exposed to it since fire was first invented.

A Swedish study in 2002 was the first to reveal that high levels of acrylamide formed during the baking or frying of potato and cereal products.

And since then researchers have been trying to make sure the risks from the chemical are kept to a minimum.

Infants and toddlers are more at risk of exposure because of their smaller body weight, and their high intake of cereal-based foods.

Basically, the advice is another reason to eat a healthy, balanced diet - and make sure your children do too.

- Published26 October 2015