Adopted Romanian orphans 'still suffering in adulthood'

- Published

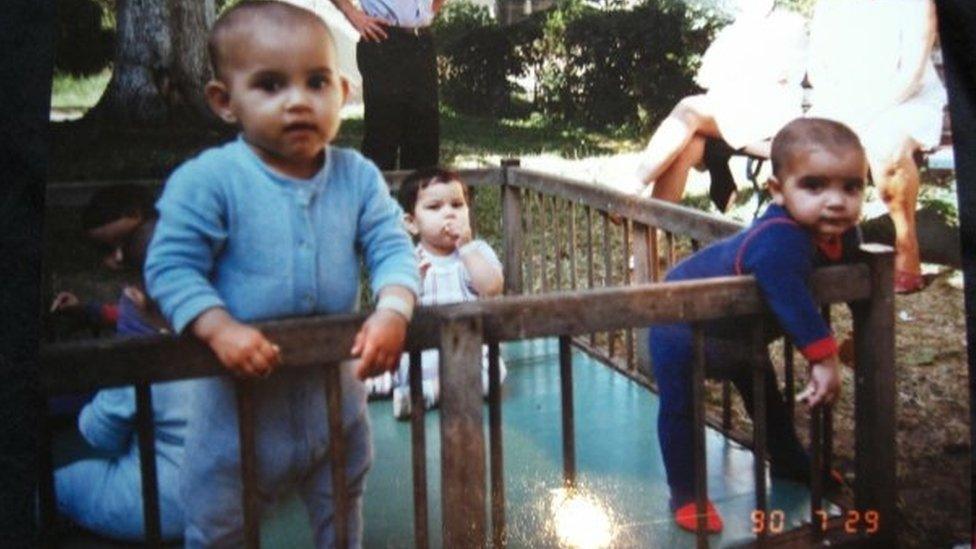

Adi (left) spent two and a half years in a Romanian orphanage

Many young children adopted from Romanian orphanages by UK families in the early 90s are still experiencing mental health problems even in adulthood, researchers say.

Despite being brought up by caring new families, a long-term study of 165 Romanian orphans found emotional and social problems were commonplace.

But one in five remains unaffected by the neglect they experienced.

Adi Calvert, 28, says she is unscathed by the trauma of her early life.

She spent two and half years in a Romanian orphanage before being adopted by a loving couple from Yorkshire, who also adopted a younger baby girl.

Adi says she doesn't remember the orphanage, but she does recall being frightened of not having enough water to drink after she was adopted.

"I was really dehydrated before, and I remember panicking a lot about water and where I was going to get it.

"I even drank from a hose in the garden when I was very small."

She puts a hatred of swimming and cold water when she was younger down to the cold baths she was given in the orphanage.

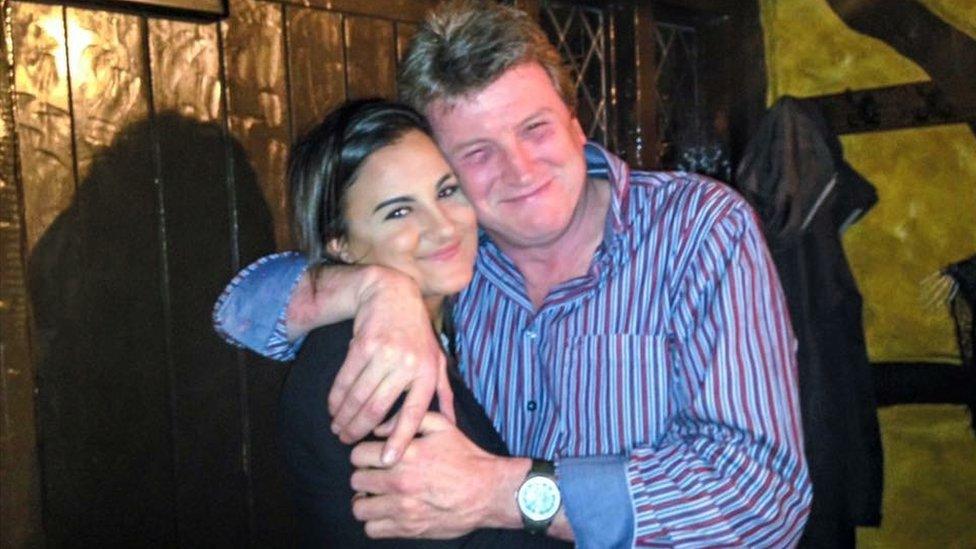

Adi grew up in Yorkshire with her caring adoptive parents before going to drama school

Now an actor, living in London - known by her stage name Ionica - Adi shows none of the long-lasting psychological scars of being neglected, deprived and malnourished during her early years.

"I'm really quite fine. I've known about it forever and it's part of me but I don't dwell on it.

"I get on really well with my adoptive parents and I'm proud that I have this life now," she says.

Writing in The Lancet, researchers from King's College London, the University of Southampton and from Germany, want to find out more about what makes people like Adi able to cope after such a deprived start in life by scanning their whole genomes.

However, most of the Romanian children brought to the UK between 1990 and 1992 have not fared so well.

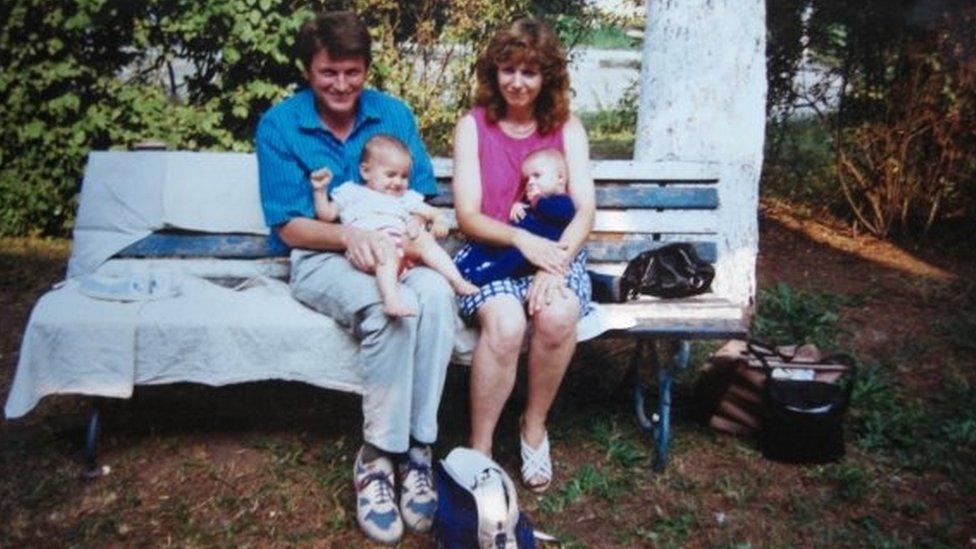

Adi was adopted along with another girl who became her sister - she also has two brothers

Initially, all 165 were struggling with developmental delays and malnourishment.

While many of those who spent less than six months in an institution showed remarkable signs of recovery by the age of five or six, children who had spent longer periods in orphanages had far higher rates of social, emotional and cognitive problems during their lives.

Common issues included difficulty engaging with other people, forming relationships and problems with concentration and attention levels which continued into adulthood.

This group was also three to four times more likely to experience emotional problems as adults, with more than 40% having contact with mental health services.

Despite their low IQs returning to normal levels over time, they had higher rates of unemployment than other adopted children from the UK and Romania.

The research team said this was the first large-scale study to show that deprivation and neglect during early childhood could have a profound effect on mental health and wellbeing in later life.

'Loving family'

Prof Edmund Sonuga-Barke, study author from King's College London, said it was possible that "something quite fundamental may have happened in the brains of those children, despite the families and schools they went to".

And he said getting children out of those neglected situations as soon as possible "and into a loving family" was crucial.

Prof Sonuga-Barke said: "This highlights the importance of assessing patients from deprived backgrounds when providing mental health support and carefully planning care when these patients transfer from child to adult mental health care."

Commenting on the research, Prof Frank Verhulst, from Erasmus University Medical Centre in the Netherlands, said many young children could be similarly affected.

"This finding is true for millions of children around the world who are exposed to war, terrorism, violence, or mass migration.

"As a consequence, many young children face trauma, displacement, homelessness, or family disruption."