Should the NHS have its own tax?

- Published

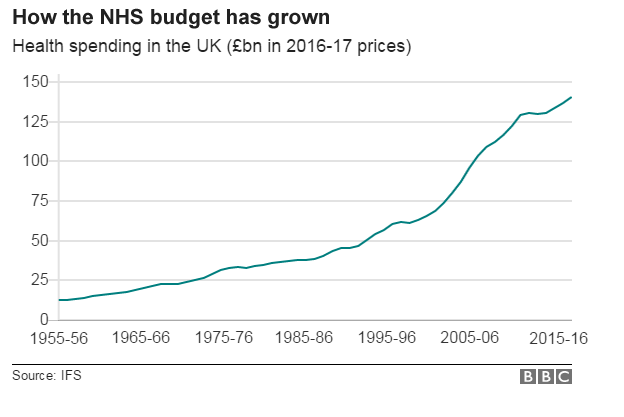

The NHS in England is under financial pressure. There is an intensifying debate about whether more money is needed and if so how much.

Among the options being suggested is a dedicated tax for the health service - transparent, easily understandable and less prone to political interference, or so the theory goes. So how realistic might it be?

The ring-fencing of tax for a specific purpose is known as hypothecation. One example, though not technically a tax, is the television licence fee, which is a levy specifically to fund the BBC.

The idea of a hypothecated tax for health has been knocked back and forth between economists for many years.

Dr Henry Marsh: 'We need a new tax to save the NHS'

Public 'back tax rises for healthcare'

10 charts that show why the NHS is in trouble

A panel of health experts has now backed hypothecation, or at least included it in a shortlist of policies for raising extra revenue.

The panel includes:

former NHS England head Sir David Nicholson

former Royal College of GPs head Clare Gerada

former Royal College of Nursing head Peter Carter

Patients Association chief executive Katherine Murphy

Commissioned by the Liberal Democrats, they have produced an interim set of proposals. Their final report is due out in the next few months.

'Clear benefits'

The expert panel argues that more money is needed than currently planned and this should come from taxation.

Income tax and National Insurance (NI) are options, says the panel, but a dedicated health and care tax would offer "clear benefits".

It would "improve understanding of what health and care cost, and enhance transparency about how our taxes our used".

National Insurance, so the thinking goes, could be the basis for a new health and care tax.

In other words, the current proceeds of NI would all be targeted at the NHS.

It just so happens that the yield to the government from NI, about £126bn annually, is not far off the total spend on the NHS across the UK.

This would reflect the original purpose of NI after World War Two, which was to allow workers to insure themselves against sickness or other loss of earnings.

The lines have since become blurred, with NI now in effect an extension of income tax.

The panel's call for more money will hit taxpayers' wallets, whether its through income tax or a new health and social care levy.

The experts believe an extra £20bn is needed for the NHS in 2020 over and above current plans, with a few billion more needed for social care.

That would represent a big hit on taxpayers, individual or corporate.

But the supporters of a dedicated health and social care tax believe it would give voters reassurance that their money was going to the right place.

What are the downsides?

So what's the catch? To start with, the Treasury has always hated the idea of hypothecation.

The chancellor's flexibility over tax and public spending decisions is reduced if certain taxes are earmarked in advance for specific purposes.

Dr Clare Gerada supports a hypothecated tax

And what if during a recession the yield from a health and care tax is reduced? In theory, spending on the NHS would have to fall.

If extra top-ups from different taxes are brought in, then the system becomes confused and drifts back to what it is now.

Scotland, of course, has its own tax-raising powers, and all the devolved nations make their own decisions about health spending.

Making hypothecation work just in England if it involves UK-wide tax revenue could be problematic.

Some argue that extra money for the NHS is not the issue anyway.

A recent report from the regulator NHS Improvement said that health trusts in England could save £400m a year simply by running their IT and payroll systems more effectively.

There is a case for more efficiency in the NHS and better use of resources in the face of rising patient demand.

The debate will continue. Earmarking tax for health and social care will be part of it.

Proponents will need to show that patient care will be improved and convince taxpayers that will be the case.