Right-to-die case: I face unbearable death

- Published

A man with terminal motor neurone disease has told the High Court he faces an "unbearable death" because of the law on assisted dying.

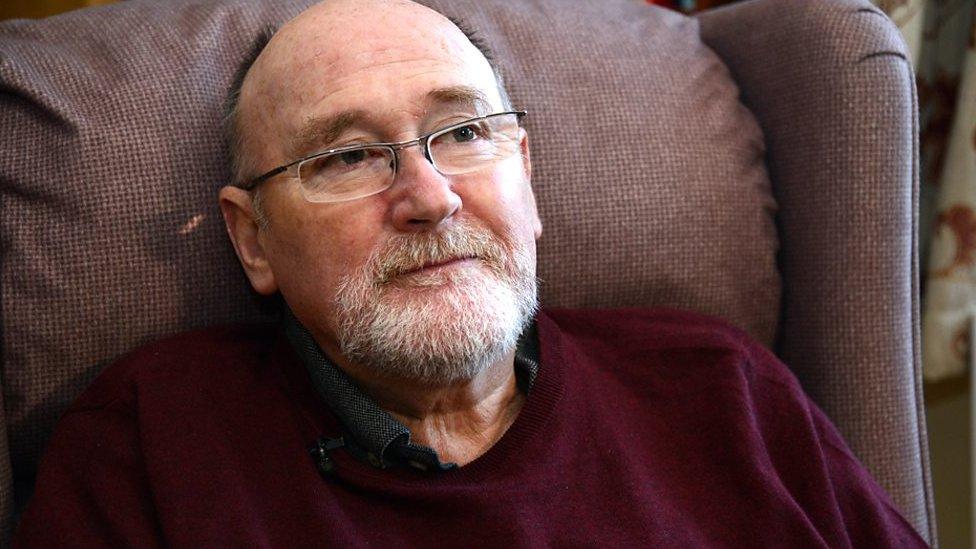

Noel Conway, 67, who was diagnosed in November 2014 and is not expected to live beyond 12 months, said he should be free to determine his own death.

Mr Conway, from Shrewsbury, attended court in a wheelchair and on a ventilator.

The case is the first heard since the law was challenged in 2014 and 2015.

Right-to-die campaigners lost an appeal to the Supreme Court in 2014 and this was followed by a debate in Parliament which concluded with MPs rejecting an attempt to introduce assisted dying in 2015.

The campaign group Dignity in Dying is supporting the legal bid.

Before his illness Noel Conway was a keen skier, climber and cyclist

Mr Conway wants permission to bring a judicial review which could result in terminally ill adults who meet strict criteria making their own decisions about ending their lives.

Richard Gordon QC, who is representing Mr Conway, said: "He wishes to die in the country in which he was born and has lived for his whole adult life.

"The choices facing him therefore are stark: to seek to bring about his own death now whilst he is physically able to do but before he is ready; or await death with no control over when and how it comes."

He said that Mr Conway contended that these choices, forced upon him by the provisions of the criminal law, violated his human rights.

He wants a declaration that the Suicide Act 1961 is incompatible with Article 8, of the Human Rights Act 1998 which relates to respect for private and family life, and Article 14, which protects from discrimination.

If the judges rule that Mr Conway has an arguable case, they will be asked to direct that it is heard as quickly as possible.

Lord Justice Burnett, sitting in London with Mr Justice Charles and Mr Justice Jay, said at the start of the hearing, which is due to last half a day, that they were minded to reserve their decision "only for a relatively short time".

Before his illness, Mr Conway, who is married, with a son, daughter, stepson and grandchild, was fit and active, enjoying hiking, cycling and travelling.

His condition means that whilst he retains full mental capacity, his ability to move, dress, eat and deal with personal care independently has diminished considerably.

At present there is a blanket prohibition on providing a person with assistance to die.

Noel Conway and his wife, Carol, at home in Shropshire

Mr Conway has said: "I feel very strongly that it is a dying person's right to determine how they die and when they die. The current law denies me this right.

"Instead, I am being condemned to unbearable suffering in my final months. I may die by suffocation or choking, or I could become completely unable to move or communicate.

"The only way for me to have some control is to refuse use of my ventilator, but there is no telling how long it would take for me to die, or whether my suffering could be managed.

"I'm going to die anyway. It's a question of whether I die with or without suffering and on my own terms or not.

"I'm bringing this case not just for me, but for all others facing terminal illness who want and deserve to have the option of a safe, dignified assisted death."

Protective law

But a spokesman for the Care Not Killing Alliance said that changing the law would send out the wrong message.

"Changing the law would send out a negative message about those who are terminally ill, disabled or old and might pressure some into ending their lives because they feel that they have become either a financial or care burden.

"The current law exists to protect those who have no voice against exploitation and coercion.

"It acts as a powerful deterrent to would-be abusers and does not need changing."

A case brought by Tony Nicklinson - who suffered from paralysis after a stroke - was ultimately dismissed in 2014 by the Supreme Court, which stated it was important that Parliament debated the issues before any decision was made by the courts.

Mr Conway's case is different in that he has a terminal illness and his legal team are setting out a strict criteria and clear potential safeguards to protect vulnerable people from any abuse of the system.