Controlled amino acid diet 'could help cancer treatment'

- Published

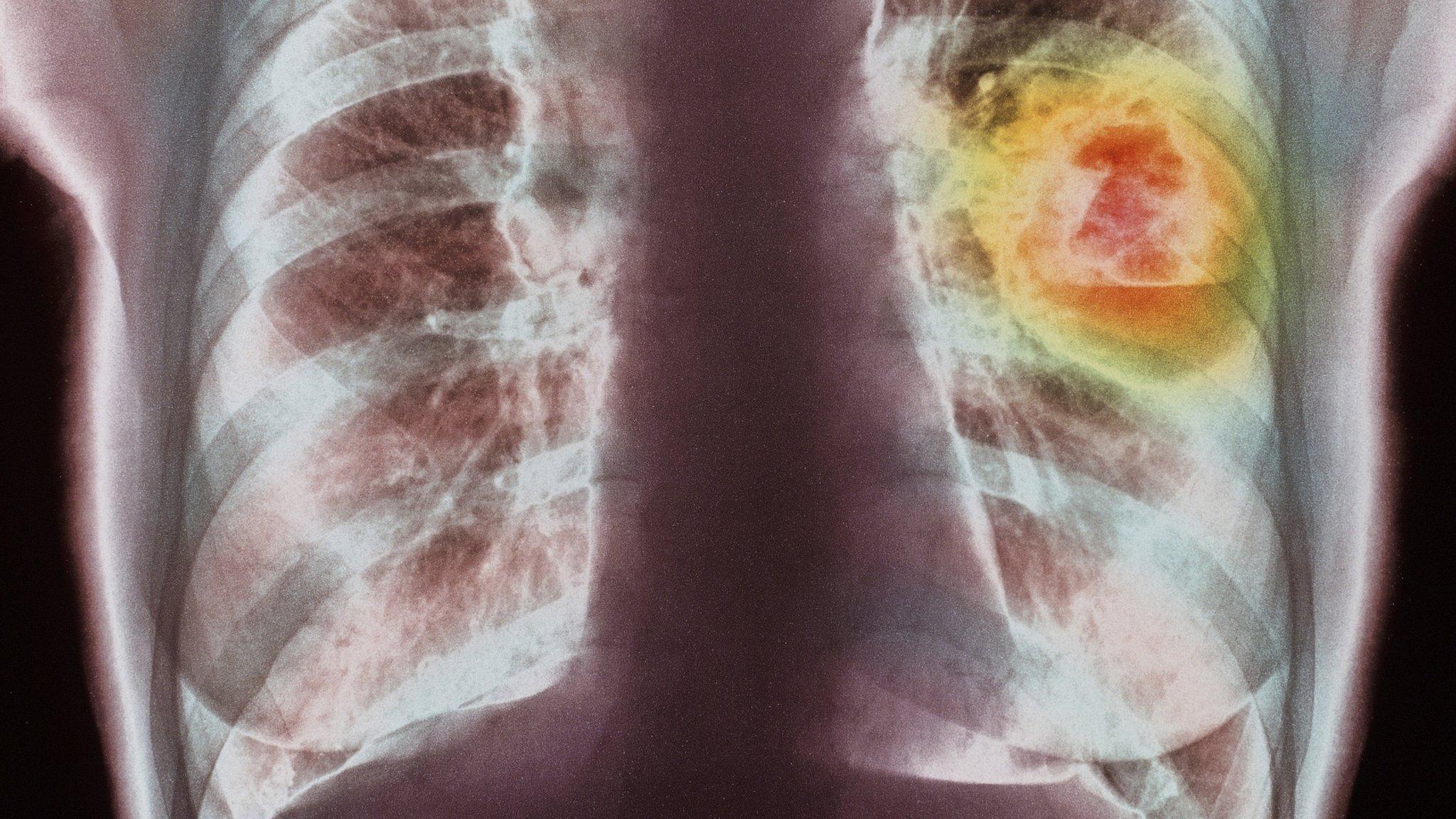

The research suggests the restricted diet could help the effectiveness of chemotherapy

A controlled diet that restricts certain amino acids could be used as an additional treatment for some cancer patients, according to Cancer Research UK.

Researchers found that removing two non-essential amino acids, serine and glycine, from the diet of mice slowed the development of tumours.

The diet could also make traditional cancer treatments more effective.

But the report's authors warn against following a do-it-yourself diet.

The report by the Cancer Research UK Beatson Institute and the University of Glasgow is published in Nature, external.

The researchers found that the development of lymphoma and intestinal cancer slowed in mice fed a diet without serine and glycine.

The restricted diet also made some cancer cells more susceptible to chemicals known as reactive oxygen species.

These same chemicals are boosted by chemotherapy and radiotherapy suggesting it could make the treatments more effective at killing cancer cells.

'Safe and gentle'

Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins but the study's authors warn against anyone cutting out protein from their diet.

"Our diet is complex, and protein - the main source of all amino acids - is vital for our health and well-being. This means that patients cannot safely cut out these specific amino acids simply by following some form of home-made diet," says Prof Karen Vousden, the study co-author and Cancer Research UK's chief scientist.

"This kind of restricted diet would be a short-term measure and must be carefully controlled and monitored by doctors for safety."

She said the next step was to do clinical trials to see if a specialised diet without these amino acids was safe and helped slow tumour growth like it did in mice.

The researchers acknowledged that devising a diet without these two amino acids would be quite difficult and they would test it on healthy people first to see how tolerable it was and "how easy it was to stick to and how it affects our levels of the two amino acids".

They also need to work out which patients are most likely to benefit, as they found the diet was less effective in tumours with an activated Kras gene, which is seen in most pancreatic cancers.

Prof Vousden told the BBC News website the diet would be a "fairly safe and gentle way to supplement conventional therapies, that means you don't have to take yet more drugs".

- Published23 January 2017

- Published4 February 2014

- Published6 October 2010