'Exciting' blood test spots cancer a year early

- Published

Doctors have spotted cancer coming back up to a year before normal scans in an "exciting" discovery.

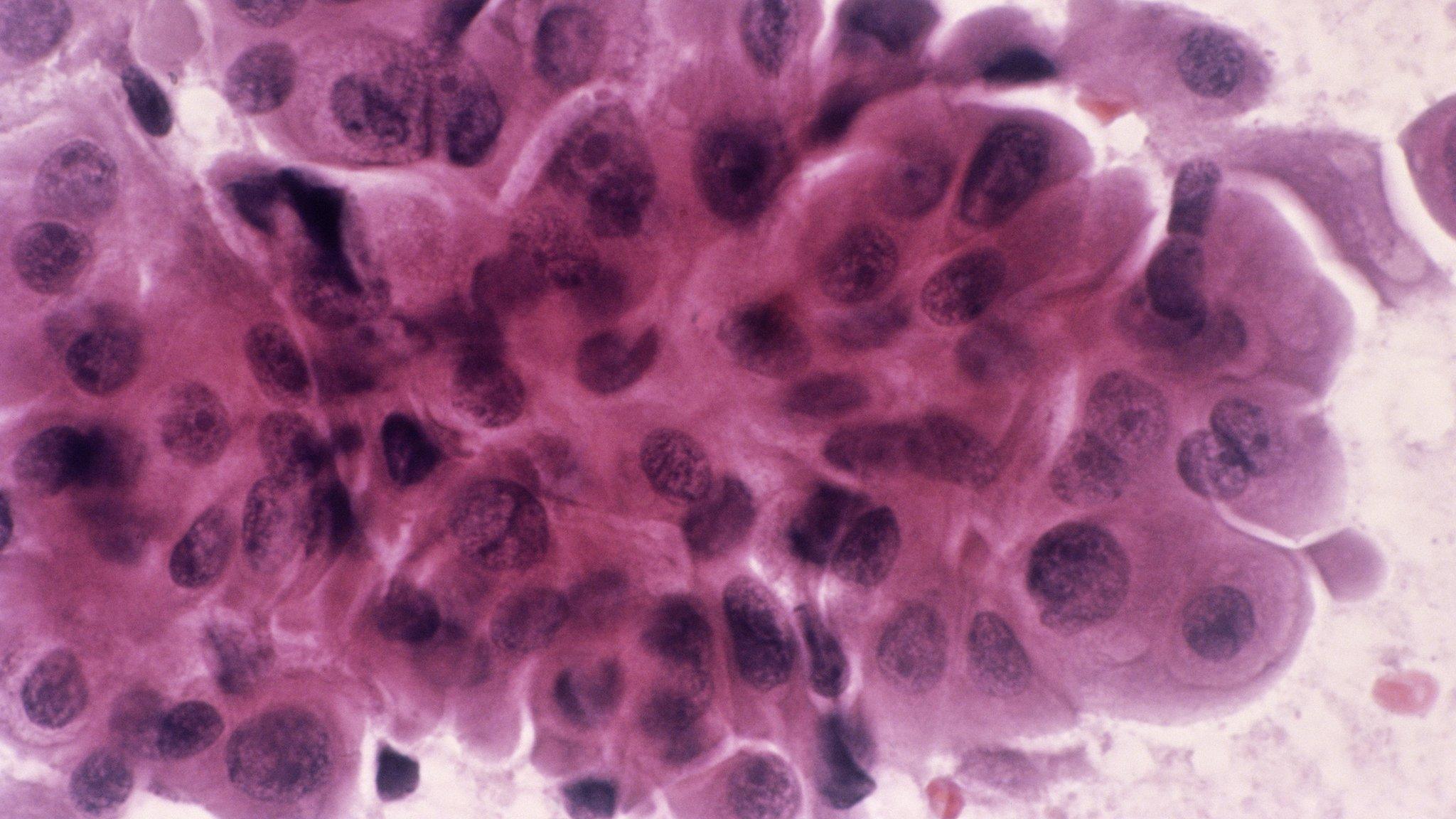

The UK team was able to scour the blood for signs of cancer while it was just a tiny cluster of cells invisible to X-ray or CT scans.

It should allow doctors to hit the tumour earlier and increase the chances of a cure.

They also have new ideas for drugs after finding how unstable DNA fuels rampant cancer development.

The research project was on lung cancer, but the processes studied are so fundamental that they should apply across all cancer types.

Lung cancer kills more people than any other type of tumour and the point of the study is to track how it can "evolve" into a killer that spreads through the body.

Blood test

In order to test for cancer coming back, doctors need to know what to look for.

In the trial, funded by Cancer Research UK, samples were taken from the lung tumour when it was removed during surgery.

A team at the Francis Crick Institute, in London, then analysed the tumour's defective DNA to build up a genetic fingerprint of each patient's cancer.

Then blood tests were taken every three months after the surgery to see if tiny traces of cancer DNA re-emerged.

The results, outlined in the journal Nature, external, showed cancer recurrence could be detected up to a year before any other method available to medicine.

The tumours are thought to have a volume of just 0.3 cubic millimetres when the blood test catches them.

'New hope'

Dr Christopher Abbosh, from the UCL Cancer Institute, said: "We can identify patients to treat even if they have no clinical signs of disease, and also monitor how well therapies are working.

"This represents new hope for combating lung cancer relapse following surgery, which occurs in up to half of all patients."

So far, it has been an early warning system for 13 out of 14 patients whose illness recurred, as well as giving others an all-clear.

In theory, it should be easier to kill the cancer while it is still tiny rather than after it has grown and become visible again.

However, this needs testing.

Prof Charles Swanton, from the Francis Crick Institute, told the BBC: "We can now set up clinical trials to ask the fundamental question - if you treat people's disease when there's no evidence of cancer on a CT scan or a chest X-ray can we increase the cure rate?

"We hope that by treating the disease when there are very few cells in the body that we'll be able to increase the chance of curing a patient."

Janet Maitland, 65, from London, is one of the patients taking part in the trial.

She has watched lung cancer take the life of her husband and was diagnosed herself last year.

She told the BBC: "It was my worst nightmare getting lung cancer, and it was like my worse nightmare came true, so I was devastated and terrified."

But she had the cancer removed and now doctors say she has a 75% chance of being cancer-free in five years.

"It's like going from terror to joy, from thinking that I was never going to get better to feeling like a miracle's been acted," she said.

And taking part in a trial that should improve the chances for patients in the future is a huge comfort for her.

"I feel very privileged," she added.

Evolution

The blood test is actually the second breakthrough in the massive project to deepen understanding of lung cancer.

A bigger analysis, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed the key factor - genetic instability - that predicted whether the cancer would return.

Multiple samples from 100 patients containing 4.5 trillion base pairs of DNA were analysed.

DNA is packaged up into sets of chromosomes containing thousands of genetic instructions.

The team at the Francis Crick Institute showed tumours with more "chromosomal chaos" - the ability to readily reshuffle large amounts of their DNA to alter thousands of genetic instructions - were those most likely to come back.

Prof Charles Swanton, one of the researchers, told the BBC News website: "You've got a system in place where a cancer cell can alter its behaviour very rapidly by gaining or losing whole chromosomes or parts of chromosomes.

"It is evolution on steroids."

That allows the tumour to develop resistance to drugs, the ability to hide from the immune system or the skills to move to other tissues in the body.

'Exciting'

The first implication of the research is for drug development - by understanding the key role of chromosomal instability, scientists can find ways to stop it.

Prof Swanton told me: "I hope we'll be able to generate new approaches to limit it and bring evolution back from the brink, perhaps reduce the evolutionary capacity of tumours and hopefully stop them adapting.

"It's exciting on multiple levels."

The scientists say they are only scratching the surface of what can be achieved by analysing the DNA of cancers.

Follow James on Twitter., external

- Published27 August 2015

- Published28 February 2017