Premature lambs kept alive in 'plastic bag' womb

- Published

The premature lambs matured and grew a wool

Scientists have been able to keep premature lambs alive for weeks using an artificial womb that looks like a plastic bag.

It provides everything the foetus needs to continue growing and maturing, including a nutrient-rich blood supply and a protective sac of amniotic fluid.

The approach might one day help premature human babies have a better chance of survival, experts hope.

Human trials may be possible in a few years, according to researchers.

First, more tests in animals are needed to check it is safe enough to progress, the researchers say in the journal Nature Communications, external.

The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia team insists it is not looking to replace mothers or extend the limits of viability - merely to find a better way to support babies who are born too early.

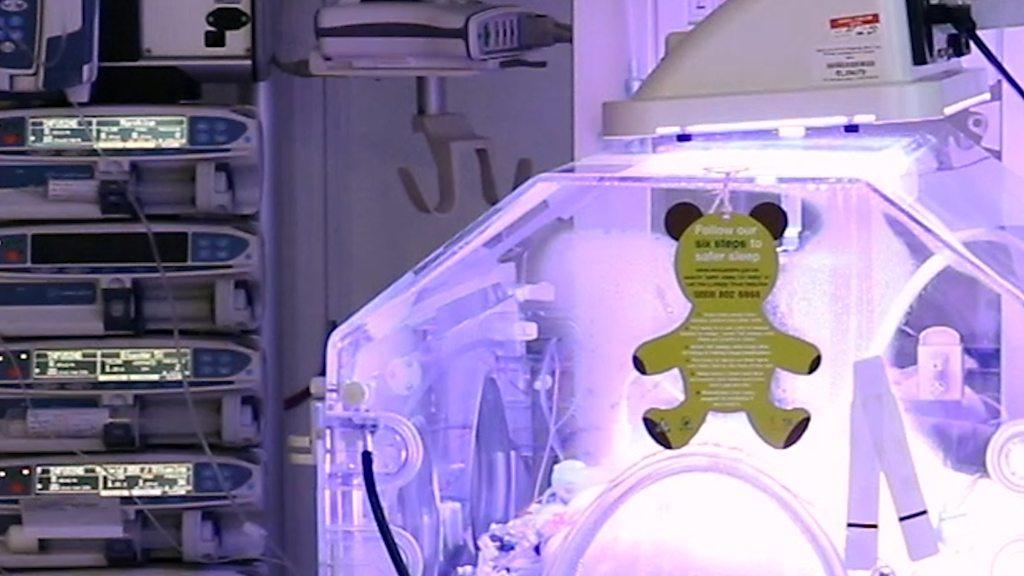

Currently, very premature infants, born at around 23 weeks of gestation, are placed in incubators and put on ventilators to help them breathe, but this can damage their lung development.

Plastic bag womb

The plastic "biobag" womb contains a mixture of warm water and added salts, similar to amniotic fluid, to support and protect the foetus.

This fluid is inhaled and swallowed by the growing foetus, as would normally happen in the womb. Gallons of the mixture are steadily flushed through the bag each day to ensure a continuous fresh supply.

The bagged lamb cannot get a supply of oxygen and nutrients from its mum via the placenta. Instead, it is connected to a special machine by its umbilical cord, which does the job.

The baby lamb's heart does all the pumping work, sending "old, used" blood out to the machine to be replenished before it returns back to the body again.

The whole system is designed to closely mimic nature and buy the tiniest newborns a few weeks to develop their lungs and other organs.

Researcher Dr Emily Partridge explained: "The challenging age that we are trying to offset is that 23- to 24-week baby who is faced with such a challenge of adapting to life outside of the uterus on dry land, breathing air when they are not supposed to be there yet."

In babies born preterm, external, the chance of survival at less than 23 weeks is close to zero, while at 23 weeks it is 15%, at 24 weeks 55% and at 25 weeks about 80%.

The premature lambs in the study, equivalent in age to 23-week-old human infants, appeared to develop normally in their bags.

They opened their eyes, grew a woolly coat and appeared comfortable living in their polyethylene homes.

After 28 days, when their lungs had matured enough, the lambs were released so they could start breathing air.

Shortly after, the lambs were then killed so the researchers could study their brains and organs in detail to see how well they had grown.

In later experiments, however, a few more bagged lambs were allowed to survive and were bottle-fed by the team.

"They appear to have normal development in all respects," said lead investigator Dr Alan Flake.

There are still many potential problems to overcome, however.

There is a significant risk of infection, even though the biobag is sterile and sealed. Finding the right mix of nutrients and hormones to support a human baby will also be a challenge.

Even if the work can progress, it's not clear how parents-to-be might feel about it.

Fellow researcher Dr Marcus Davey said: "We envisage the unit will look pretty much like a traditional incubator. It will have a lid and inside that warmed environment would be the baby inside the biobag."

Prof Colin Duncan, professor of reproductive medicine and science at the University of Edinburgh, said: "This study is a very important step forward. There are still huge challenges to refine the technique, to make good results more consistent and eventually to compare outcomes with current neonatal intensive care strategies.

"This will require a lot of additional pre-clinical research and development and this treatment will not enter the clinic any time soon."

Follow Michelle on Twitter, external

- Published25 April 2017

- Published15 February 2017