Frozen 'space sperm' passes fertility test

- Published

Healthy baby mice have been born using freeze-dried sperm stored in the near-weightless environment of space.

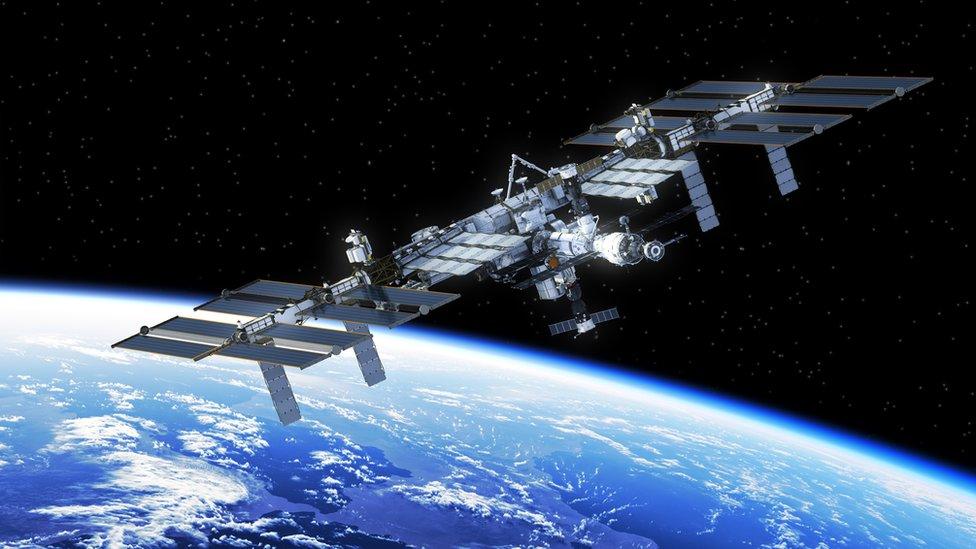

The Japanese team behind the gravity-breaking experiment on the International Space Station (ISS) say it shows that transporting the seeds of life away from Earth is feasible.

Sperm banks could even be made on the Moon as a back-up for Earth disasters, they told a leading science journal., external

It is unclear if this will ever help humans populate space, however.

Space pups

Sustaining life in space is challenging to say the least.

On the ISS, radiation is more than 100 times higher than on Earth. The average daily dose of 0.5mSv from the cosmic rays is enough to damage the DNA code inside living cells, including sperm.

Microgravity also does strange things to sperm.

In 1988, German researchers sent a sample of bull semen into orbit on a rocket and discovered that sperm were able to swim much faster in low gravity,, external although it was not clear whether this gave a fertility advantage.

The space pups grew into healthy adult mice

Another space test showed fish eggs could be fertilised and develop normally, external during a 15-day orbital flight, suggesting a brief trip into space might not be too harmful for reproduction - at least for vertebrates.

The freeze-dried mouse sperm samples were stored on the space station for nine months before being sent back down to Earth and thawed at room temperature, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reports.

Although sperm DNA was slightly damaged by the trip, it still did the job of fertilising mouse eggs and creating apparently healthy "space pups".

Fertilisation and birth rates were similar to healthy "ground control" mice.

The space pups had only minor differences in their genetic code and grew to adulthood. A select few were allowed to mate and became mums and dads themselves.

The researchers, Sayaka Wakayama and colleagues from the University of Yamanashi, suspect some of the sperm DNA damage is repaired by the egg once it has been fertilised.

"If sperm samples are to be preserved for longer periods in space, then it is likely that DNA damage will increase and exceed the limit of the [egg] oocyte's capacity for repair.

"If the DNA damage occurring during long-term preservation is found to have a significant effect on offspring, we will need to develop methods to protect sperm samples against space radiation, such as an ice shield," they said.

Lunar sperm banks

Once they've cracked that, they can set their sights on the Moon sperm banks.

"Underground storage on the Moon, such as in lava tubes, could be among the best places for prolonged or permanent sperm preservation because of their very low temperatures, protection from space radiation by thick bedrock layers, and complete isolation from any disasters on Earth," the scientists say.

But that still leaves the massive question of whether mammals, including us humans, can permanently live and procreate in space.

Mouse, external and human studies, external so far suggest perhaps not.

Prof Joseph Tash, a Nasa-supported physiologist at the University of Kansas Medical Center, said although the latest findings were interesting, the ISS was a somewhat sheltered environment to use as the test zone for space.

"The ISS orbit is within the protection of the Van Allen radiation belt - the magnetic field that diverts most high energy radiation particles from hitting the earth or the ISS.

He said the actual risk of radiation damage at the Moon and beyond would be much higher.

"Ovaries and testes are the most sensitive organs to both acute and chronic radiation exposure."

He said the feasibility of mammalian reproduction in space beyond the Van Allen belt would depend on the creation of "radiation-hardened" facilities that could protect sperm, eggs and embryos from harm.

"Given the nine month gestation for humans, the pregnant mother would also need to be protected by such a facility. So it presents very real habitat, medical, social, and psychological questions that need to be addressed as well."

Follow Michelle on Twitter, external