Spotting the earliest signs of Alzheimer's

- Published

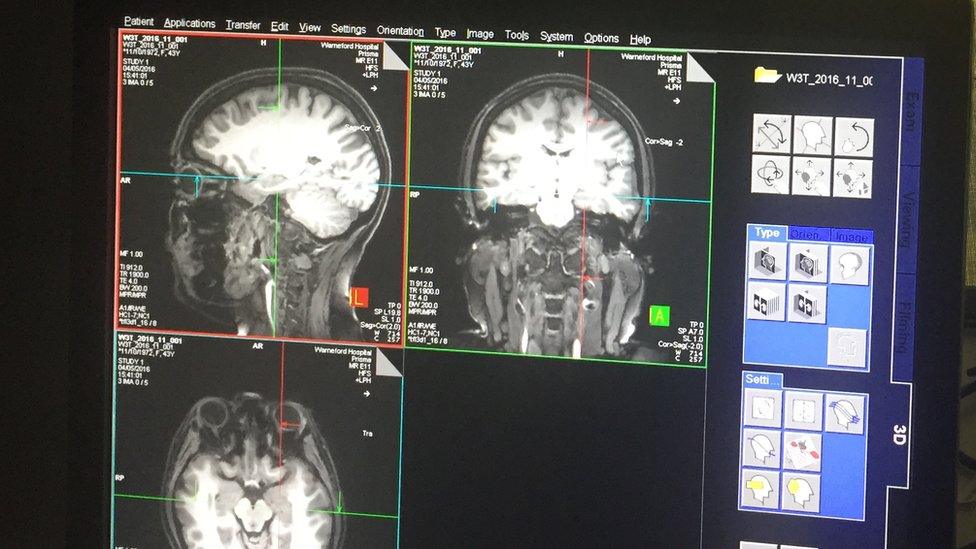

The new study will be the most in-depth yet on Alzheimer's disease

Work is about to begin on a new study to find the earliest signs of Alzheimer's disease, many years before symptoms like memory loss and confusion become obvious.

Scientists believe this is the best time to be using drugs to stop Alzheimer's from developing further.

Finding a treatment that can combat the disease has been one of medicine's major challenges. Results from drug trials have repeatedly been disappointing.

This new study will involve up to 50 tests on 250 volunteers and will include brain scans, cognitive testing and measure the way people walk.

The difficulty that doctors face is that the disease can start to affect the brain several years before the symptoms are visible.

Patricia Latto, who is in her nineties, has Alzheimer's. Evidence from her diary suggests the disease had begun to take hold more than a decade before being recognised.

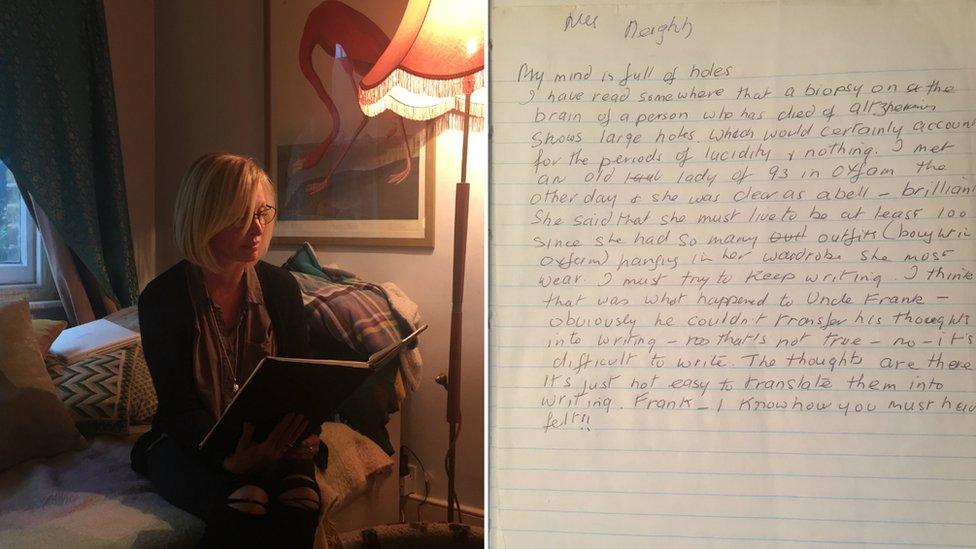

Patricia's story: 'My mind is full of holes'

Patricia Latto was clearly upset and concerned about her mental deterioration in her mid-60s and kept a diary.

"I am writing this because I'm afraid I have Alzheimer's…" the diary entry begins, dated 12 May 1990.

"And now I have slipped into a no-man's land - no, a limbo, of not remembering and what has shocked me most - not being able to write clearly."

Patricia Latto had fears about her condition 20 years before she was officially diagnosed

She seemed to be using the diary as a memory test. It is full of lengthy passages of poetry and Shakespeare.

"Tonight I have quoted Yeats, Masefield, Shakespeare word for word without hesitation… So why do I find it so difficult to sign my own name. It just doesn't make sense."

In one diary entry she writes: "My mind is full of holes."

Cate Latto discovered her mother had been keeping a diary on her worsening mental health

Twenty years later Patricia was officially diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.

The diary was discovered by Patricia's daughter Cate Latto, when she was clearing out her mother's things after she was moved into a care home for specialist support.

"It must have been so frightening for her," says Cate, "To have her world shrinking, and being too scared to even talk about it."

Cate is now taking part in separate research by the Alzheimer's Society, called Prevent Dementia Study, which involves people with some risk factors for the disease, such as a family history or certain genes.

Detecting the earliest signs

Patricia Latto's experience illustrates one of the key challenges of dealing with Alzheimer's disease. By the time it is clinically diagnosed, it can be too late to do anything about it, because by then the damage caused to the brain is irreversible.

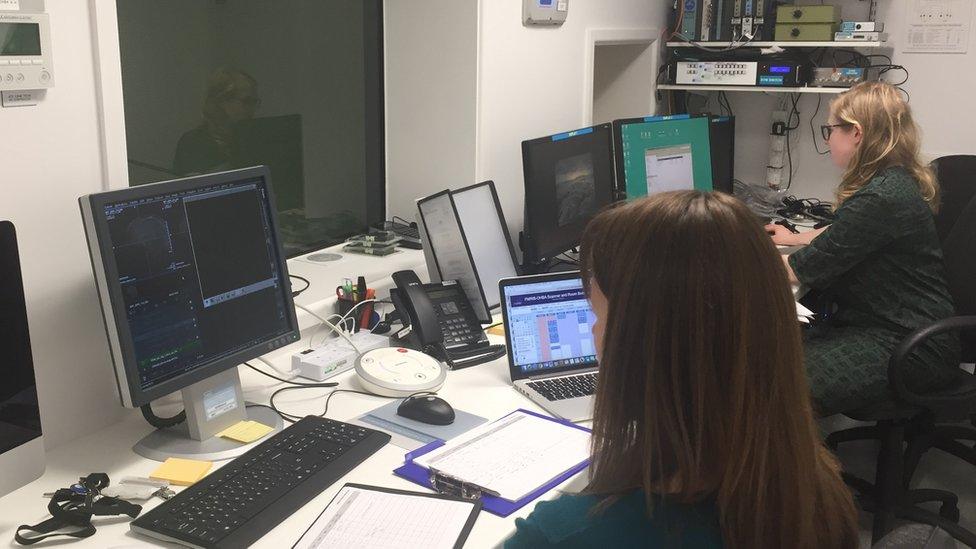

The Deep and Frequent Phenotyping Study, involving eight UK universities and the Alzheimer's Society, and led by Prof Simon Lovestone at the University of Oxford, will aim to find the very earliest signs of Alzheimer's, between 10 and 20 years before the symptoms become more obvious.

The huge study is being led by the University of Oxford

Range of rigorous tests

The Deep and Frequent Phenotyping Study includes regular brain scans, cognitive and memory testing, retinal imaging, blood tests and the use of wearable technology to measure movement and gait.

Prof Lynn Rochester, from the Clinical Ageing Research Unit at Newcastle University, says tiny, almost imperceptible changes in the way people walk could be a very early sign of Alzheimer's disease.

"People think of walking as a task which involves muscles contracting and relaxing and you get from A to B," she says.

"But in fact walking is now considered as much a cognitive task as it is a motor task and we've got a really large body of research that shows that."

The researchers are using small devices, fitted to the small of the back, to measure movement over a period of a week. Small changes to the pattern of walking can be indicative of deeper problems in the brain, eventually leading to dementia. Scientists would be looking for variations in walking which could involve changes in speed, balance and unusual movements not explained by normal ageing.

"If you think about your footsteps in the sand, and how even and well placed they are. We're looking at very, very subtle changes in how those footsteps might appear," Prof Rochester explains.

Minuscule changes in a person's walking pattern could be an early sign of the onset of Alzheimer's

The study, described by the researchers as potentially game changing, will monitor and measure small changes on the 250 volunteers over a period of a year. Some of those involved will be at risk of developing Alzheimer's disease because of their genes or age, and others will not be at risk.

The research will generate huge amounts of data and will use complex big-data mathematical analysis to determine which tests, or combination of tests, best predict later onset of Alzheimer's.

"We're going to be throwing the book at people, using all the things that we can measure," says Clare Mackay, Professor of Imaging Neuroscience at the University of Oxford.

"Pretty much everything we know might be sensitive, we're going to do them all in the one study, which has never been done before."

Andrew Bomford's reports on the new Alzheimer's study will be broadcast on Radio 4's World at One on 26 and 27 June 2017.

- Published21 June 2017

- Published1 March 2017

- Published22 August 2016

- Published27 July 2016