Contaminated blood scandal inquiry announced

- Published

A UK-wide inquiry will be held into the contaminated blood scandal that left at least 2,400 people dead, the prime minister has confirmed.

A spokesman for Theresa May said it would establish the causes of the "appalling injustice" that took place in the 1970s and 1980s.

Thousands of NHS patients were given blood products from abroad that were infected with hepatitis C and HIV.

It's been called the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Many of those affected and their families believe they were not told of the risks involved and there was a cover-up.

Speaking to the BBC, Mrs May said: "They deserve answers, and the inquiry that I have announced today will give them those answers, so they will know why this happened, how it happened.

"This was an appalling tragedy and it should never have happened."

What is the contaminated blood scandal?

A recent parliamentary report, external found around 7,500 patients were infected by imported blood products.

Many were patients with an inherited bleeding disorder called haemophilia.

They needed regular treatment with a clotting agent Factor VIII, which is made from donated blood.

The UK imported supplies and some turned out to be infected. Much of the plasma used to make Factor VIII came from donors like prison inmates in the US, who sold their blood.

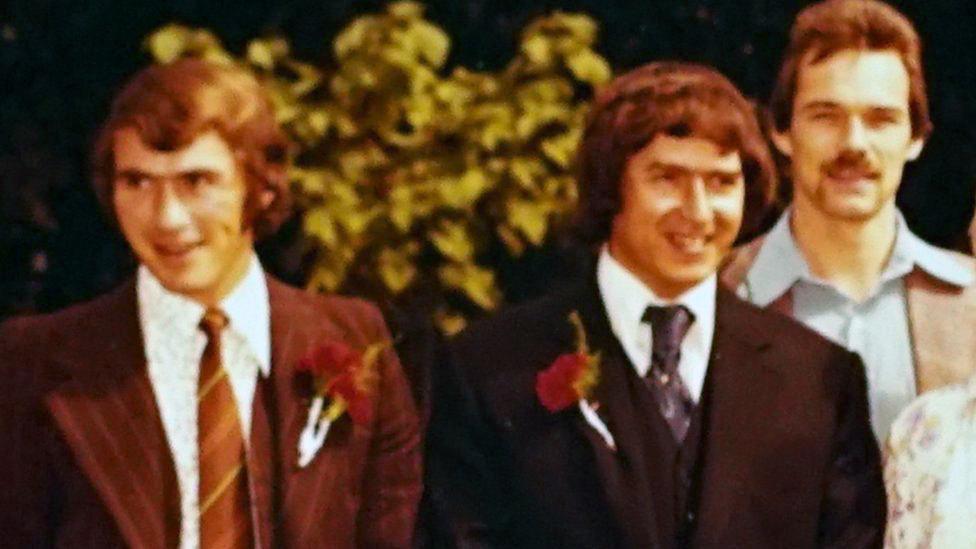

Jason Evans was just four years old when his father Jonathan, a haemophiliac, died after being infected with HIV through contaminated Factor VIII treatment.

Jason Evans' father died of Aids after being infected with contaminated blood

Jason recently discovered that in late 1984 his father had raised concerns with his doctors about Factor VIII but he says he was told "there was nothing to worry about, this is sensationalism and not to pay attention to it. And he trusted his doctor".

What will the inquiry do?

Families of those who died will be consulted about what form the inquiry should take.

It could be a public Hillsborough-style inquiry or a judge-led statutory inquiry, the prime minister confirmed.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn said the inquiry should have the potential to trigger prosecutions.

A Scottish government spokesperson said: "We were very surprised that as the new inquiry is expected to extend to Scotland, the UK government did not seek to discuss this with us in advance of their announcement. We will be seeking clarity as a matter of some urgency.

"People in England and Wales should get the same opportunity to get answers as we have already given through the Penrose Inquiry, external in Scotland."

Sir Peter Bottomley, co-chairman of the cross-party parliamentary group on haemophilia and contaminated blood, said the success of the inquiry would depend on it being able to get hold of sensitive information.

"It must have powers to get documents from pharmaceutical companies and government," he said.

Why has it taken so long?

The government has been strongly criticised for dragging its heels.

"People were acting for the best motives but just made catastrophic mistakes," says Sir Peter Bottomley MP

Greater Manchester mayor and former health secretary Andy Burnham has repeatedly called for a Hillsborough-style probe into what happened.

Mr Burnham claimed in the Commons that a "criminal cover-up on an industrial scale" had taken place.

The Downing Street announcement came hours before the government faced possible defeat in a vote on an emergency motion about the need for an inquiry.

Will victims be financially compensated?

Payments have been made to some of the people who were infected. A fund, external was established to help support survivors.

If the new inquiry finds culpability it opens the door to victims seeking large compensation payouts through the courts.

Jason Evans said his father had raised concerns with his doctors about Factor VIII before he died

Liz Carroll, chief executive of the Haemophilia Society, said: "The government has for decades denied negligence and refused to provide compensation to those affected, this inquiry will finally be able to properly consider evidence of wrongdoing."

Are blood products safe now?

Improvements in donor vetting meant that by 1986 UK patients were receiving safer treatments.

By the late 1990s, synthetic treatments for haemophilia became available, removing the infection risk.

Anyone who received a blood transfusion before 1991 is potentially at risk of Hepatitis C infection since blood donations were not screened before this date.

Blood donations are now routinely tested for infections, including hepatitis and HIV.

- Published11 April 2017

- Published26 April 2017