We must do better on baby deaths and injuries - Hunt

- Published

The NHS in England must do better at learning from mistakes to cut the number of baby deaths and injuries in childbirth, the health secretary says.

There are an estimated 1,000 cases a year where babies unexpectedly die or are left with severe brain injury.

That is out of nearly 700,000 births, which, Mr Hunt said, showed the NHS provided safe care for most.

But, he added, all unexplained cases of serious harm or death would now be independently investigated.

The Healthcare Safety Investigations Branch, set up earlier this year, will be tasked with reviewing cases.

Unveiling the new plans, Mr Hunt said he hoped this would help the NHS learn from mistakes as part of the drive to halve the overall rate of stillbirths, deaths and brain injuries by 2025 - five years earlier than previously announced.

The target was initially set in 2015 amid concern that while there had been progress on reducing cases, the improvement had not been as fast as some western countries.

But Mr Hunt conceded staffing numbers would also have to increase.

It comes as an NHS-backed review of deaths in cases where the baby was seemingly healthy as labour began found in 80% of cases improvements in care could have prevented the death.

Staffing and heavy workload was highlighted as a key issue by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership report.

'We had to fight to find the truth'

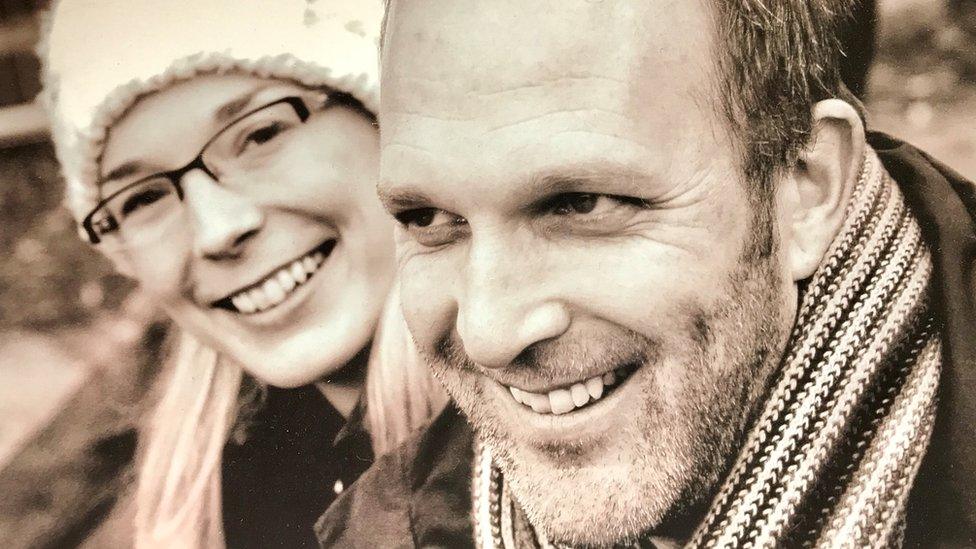

Sarah and Jack Hawkins believe if previous stillborn deaths had been investigated, their baby may have survived

Sarah Hawkins' pregnancy had gone well. But during her labour Sarah was told that her baby, Harriet, had died.

Nottingham University Hospitals Trust initially said it was because of an infection, but after Sarah and her husband Jack, who both worked at the trust, fought for an external review the full picture came to light.

There had been gross errors and mismanagement coupled with intense pressure on services.

One of the maternity units run by the trust had had to close its doors to new admissions because of under staffing.

When she was admitted, opportunities were missed to identify problems early enough.

Staff failed to diagnose she was in active labour, made mistakes monitoring the baby's heartbeat and did not respond quickly enough when the situation became critical.

The trust later admitted if it was not for the shortcomings Harriet could have survived and apologised for the "unimaginable distress and sadness caused".

Sarah said: "It's taken us 19 months to get an external, independent review. We've been trying to find answers for our daughter and it shouldn't be us trying to fight.

"It has had such a significant mental and physical impact on our mental wellbeing."

The health secretary said there were "not enough staff across the whole NHS" and that would be addressed by a major expansion in training places in the coming years.

But he also said there were steps that could be taken now to improve the way the health service dealt with mistakes.

"We make it really difficult for the NHS to learn what happened and to spread the message about what needs to be done differently next time.

"People are worried about lawyers, regulation and being fired by their own trust. We have to change a blame culture into a learning culture."

He said key to this would be the move to get the new Healthcare Safety Investigations Branch to automatically look at all cases of potentially avoidable harm.

Currently it is up to local hospitals to investigate cases or for parents to bring clinical negligence cases.

Mr Hunt said he hoped the move would give parents quick answers and ensure learning was shared across the NHS, which in turn would help curb the growing bill for settling clinical negligence claims relating to babies with brain injuries.

An average of two claims a week are being settled at the moment, with each case costing millions of pounds in lifetime care for these babies.

Mr Hunt also said the government would look into changing the law to allow coroners to investigate full-term stillbirths - currently they cannot do this, with some parents saying deaths have been classified as stillbirths to avoid the need for an inquest.

Royal College of Midwives general secretary Gill Walton welcomed the measures being taken.

But she added the findings on staffing levels were "concerning" - the union believes the NHS in England is 3,000 midwives short of what it needs.

"The increasing complexity of women being cared for in our maternity services exacerbates this issue," she said.

"We must ensure we have enough midwives and obstetricians to provide safe care throughout the maternity pathway and adequate facilities in all birth settings."

- Published3 July 2017

- Published3 July 2017

- Published3 July 2017

- Published14 May 2017

- Published13 April 2017

- Published12 June 2017