Could drugs delay the diseases of ageing?

- Published

Hilda Jaffe is still working at 95

Imagine having to ask a 95-year-old to slow down - well, I did. Hilda Jaffe was walking so fast there was a risk that the small group following her would be left behind.

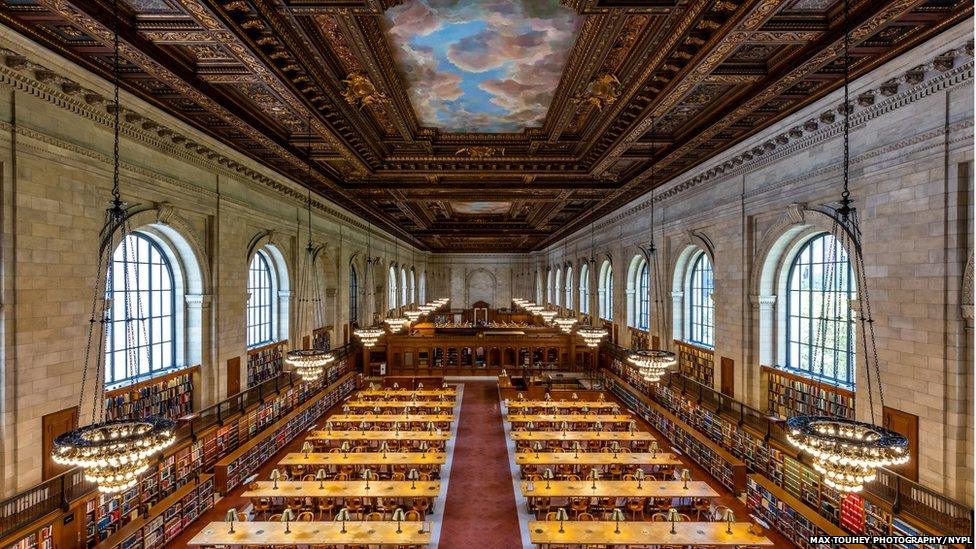

We had just met in the lobby of the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, where Hilda is a volunteer tour guide, and she was escorting us to the vast, elaborately decorated Rose Main Reading Room.

Hilda doesn't walk so much as stride. I know people 60 years her junior who are less nimble on their feet.

In common with other super-agers, Hilda has retained her zest for life and knowledge.

Hilda completes the New York Times crossword each day, belongs to two book clubs, goes to the opera, classical music concerts and the theatre.

She also goes everywhere by foot, describing New York as a "great city for older people".

Hilda on honeymoon with her late husband Gerry

I asked Hilda what was the secret of her long and healthy life?

She said: "Pick your parents; my father died at 88, my mother at 93, so it has to be genetic."

Samples of Hilda's DNA are stored in a freezer at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx.

She is among more than 600 people aged over 90 who are part of the Longevity Genes Project., external

The Rose Main Reading Room of the New York Public Library, which opened in 1911 and where Hilda Jaffe is a tour guide

Dr Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute for Aging, said what was striking about the group was what unhealthy lives many had lived.

He told me: "Almost 50% of them were overweight. Many were heavy smokers, did not exercise and had unhealthy diets - they did not do what their doctors said they should."

His research found several genetic variants among the group that appeared to confer protection against the diseases of ageing.

He says only about one in 10,000 people is lucky enough to have these protective super-ager genes, but believes science could help the rest of us.

Some pharmaceutical companies are exploring whether these genetic traits could be used to create anti-ageing drugs.

For more than 60 years metformin has been used as a very cheap first-line treatment for diabetes.

Now, trials in a variety of animals have shown they live healthier, longer lives.

Exactly how metformin might delay the diseases of ageing is not well understood, but it appears to reduce oxidative damage and inflammation in cells.

In humans, studies have linked metformin to a lower risk of heart disease, diabetes and cognitive decline.

Dr Barzilai, who is also deputy scientific director of the American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR), is planning a randomised study of 3,000 adults aged 65-79 - half will take metformin tablets each day and half a placebo or dummy pill.

About half the $70m dollars needed has been raised; it is hoped the six-year trial will start in 2018, but this may depend on the support of one or more wealthy philanthropists.

At present, the US medicines regulator, the FDA, does not recognise ageing as a medical condition.

But Dr Barzilai says if the metformin trial was successful it would provide a proof of principle that ageing can be targeted

And he believes better drugs will come in the future.

Another promising area of ageing research is cellular senescence - the process by which cells stop dividing.

Most human cells can reproduce a limited number of times - this protects against cancer as the more cells divide, the greater the chance they will accumulate errors.

Cellular senescence helps keep humans predominantly free of cancer in the first half of life.

But as we age, the senescent cells accumulate, secreting inflammatory molecules that can damage neighbouring tissue and help trigger several diseases of ageing.

Senescent cells congregate in tissue affected by ageing, such as the joints and eyes - and are implicated in both osteoarthritis and age-related macular degeneration.

Unity Biotechnology, in California, is planning to begin human trials next year of a drug to clear senescent cells from the knee.

Dr Jamie Dananberg, chief medical officer, told me: "Osteoarthritis is a key reason why it hurts to get old. Our hope is that a single injection will alleviate pain, halt and perhaps even begin to repair the knee."

Even if the drug, which might need to be injected every few months, was partially successful, it could have huge implications for improving quality of life for those affected.

Unity is also targeting eye, lung and kidney disease.

These drugs are not designed to make us live longer, but to make old age less painful and more healthy - to put more life in our years.

If they work, then more of us could emulate Hilda Jaffe and become super-agers.

Follow Fergus on Twitter., external

- Published18 December 2017