Why are some flu outbreaks so much worse than others?

- Published

Flu comes along every winter, but how many people it will infect - and just how poorly they will be - is incredibly difficult to predict. What makes one flu outbreak worse than another?

After Australia experienced its worst flu season in more than a decade, it was widely expected that the arrival of winter would see more people than usual fall ill in the UK.

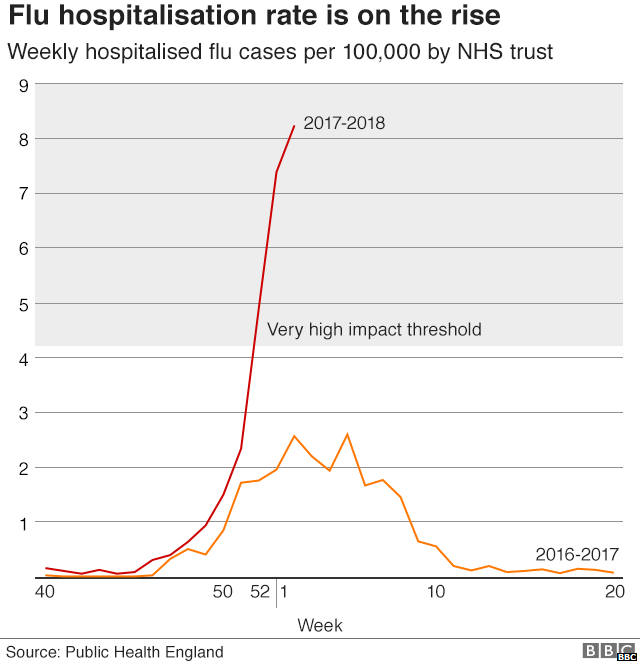

That's exactly what has happened: this flu season is the worst for seven years.

The latest figures show a 40% increase in the number of people going to GPs in England with suspected flu in the last week. Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland have also recorded increases.

Things are not expected to improve in the coming weeks - the UK has a nasty case.

Flu viruses are split into three different types: A, B and C Influenza, with lots of different strains within these.

In this year's flu season, there are four strains circulating - and about half of hospital cases are caused by the B strain.

A is usually the most lethal and is first transmitted from animals to humans.

This winter one of the dominant strains circulating in the UK is a strain of Influenza A called H3N2, or Aussie flu.

The H3N2 strain is not new, but is a more severe strain of flu than the H1N1 strain that has circulated over the last two years.

It also differs from the strains covered by the current vaccine that has been given to many people.

Why flu is so unpredictable

Flu viruses are always competing to infect and pass between people - the virus strains most successful at this are the ones that will become dominant.

Predicting which of these strains will become dominant in any given season is always a challenge.

If, like this year, the main flu viruses are sufficiently different to previous years and the strains in the flu jab, more people may be infected.

Flu viruses constantly evolve as they pass from person to person, changing their appearance so our immune system doesn't recognise them as easily.

As a good rule of thumb, if more people receive the flu vaccination, then fewer people will get flu.

The vaccine also reduces the severity of the symptoms - meaning people are less likely to go to hospital - and the risk of spreading it to other people.

Growing vaccine in eggs

However, some flu vaccines are more effective than others.

They work by getting the immune system to recognise parts of the influenza virus, so it responds more effectively when it encounters the real thing.

It takes eight or nine months to develop and manufacture enough flu vaccine for one winter.

Flu jabs are still made in the same way they have been for more than 60 years - by growing them in chicken eggs.

Technicians check eggs which are used to cultivate flu vaccines

This means scientists have to decide which strains to include in a vaccine many months before the flu season actually starts.

A big problem is that the virus keeps evolving before the vaccine is ready.

If the virus changes more than expected, or a minor strain becomes unexpectedly common, the vaccine will be less effective.

While this year's vaccine is not as effective as hoped, it is still the best first defence available.

A universal flu vaccine that would protect against all strains of flu is still many years away.

Neither is it possible to protect everyone with the vaccine that is available.

To buy enough doses, governments would need to give vaccine companies many years' notice, or build new factories to produce enough.

There is also the risk that the year everyone was vaccinated might be the year when the strains of flu are not particularly aggressive or easily spread.

The vaccine could also include the wrong strains.

Crucially, no flu vaccine is 100% effective and a small amount of people would still get ill.

When a flu outbreak becomes a pandemic

Seasonal flu - as we are currently experiencing - happens every year and usually peaks in the UK in January and February.

Most people have some immunity to it, having had flu before, or a vaccination.

Those unlucky enough to catch flu may feel very ill, but will normally recover in about a week - although it can be deadly in a small number of cases, particularly among young children and the elderly.

Pandemic flu occurs when a new virus strain emerges from an animal.

Most people have little or no immunity because they have no previous exposure to it, or similar strains.

It affects large parts of the population and spreads across many countries.

Pandemic flu typically affects younger people more than seasonal flu and there is a much higher risk of serious medical complications, hospitalisation and death.

The last time the world suffered pandemic flu was the 2009 swine flu, which spread swiftly across the world, infecting at least 171 countries and killing 457 people in the UK.

Thankfully this was not quite as severe a healthcare crisis as was first feared.

People wait in line for a vaccination shot in 2009

At times, pandemic flu can be disastrous.

The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-19 brought about the greatest number of deaths from an infectious disease since the Black Death in the 14th Century.

It infected a third of the planet's population and killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide.

Many of the victims were young, otherwise healthy adults and infection often led quickly to a deadly form of pneumonia.

At the time, no effective drugs or vaccines existed to prevent or treat it - a very different situation to the one we are now in, although we are hardly well prepared.

It is also fortunate that pandemic flu is rare - it emerged only three times in the 20th Century.

The next pandemic flu may not occur for 40 years, or it might be next year.

It is impossible to tell.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Prof Mike Turner is the head of Infection and Immunobiology at the Wellcome Trust, external, which describes itself as a global charitable foundation working to improve health for everyone.

Edited by Duncan Walker

- Published18 January 2018

- Published11 January 2018