First human eggs grown in laboratory

- Published

'It could be of huge benefit to children having cancer treatment'

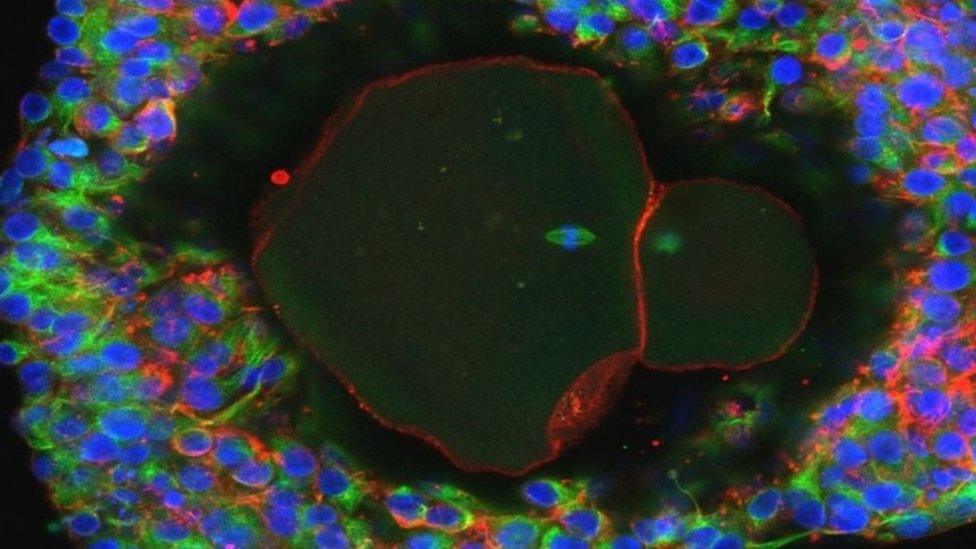

Human eggs have been grown in the laboratory for the first time, say researchers at the University of Edinburgh.

The team say the technique could lead to new ways of preserving the fertility of children having cancer treatment.

It is also an opportunity to explore how human eggs develop, much of which remains a mystery to science.

Experts said it was an exciting breakthrough, but more work was needed before it could be used clinically.

Women are born with immature eggs in their ovaries that can develop fully only after puberty.

It has taken decades of work, but scientists can now grow eggs to maturity outside of the ovary.

It requires carefully controlling laboratory conditions including oxygen levels, hormones, proteins that simulate growth and the medium in which the eggs are cultured.

'Very exciting'

But while the scientists have shown it is possible, the approach published in the journal Molecular Human Reproduction still needs refinement.

It is very inefficient with only 10% of eggs completing their journey to maturity.

And the eggs have not been fertilised, so it is uncertain how viable they are.

Prof Evelyn Telfer, one of the researchers, told the BBC: "It's very exciting to obtain proof of principle that it's possible to reach this stage in human tissue.

"But that has to be tempered by the whole lot of work needed to improve the culture conditions and test the quality of the oocytes [eggs].

"But apart from any clinical applications, this is a big breakthrough in improving understanding of human egg development."

UK scientists edit DNA of human embryos

A lab-grown, human egg made by scientists at the University of Edinburgh

The process is very tightly controlled and timed in the human body - some eggs will mature during the teenage years, others more than two decades later.

An egg needs to lose half its genetic material during development, otherwise there would be too much DNA when it was fertilised by a sperm.

This excess is cast off into a miniature cell called a polar body, but in the study the polar bodies were abnormally large.

"This is a concern," said Prof Telfer. But it is one she thinks can be addressed by improving the technology.

Work on mouse eggs, which was nailed 20 years ago, showed the technology could be used to produce live animals.

Matching this achievement in human tissue could eventually be used to help children having cancer treatment.

Cancer option

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy risks making you sterile.

Women can freeze matured eggs, or even embryos if they are fertilised with a partner's sperm, before starting treatment - but this is not possible for girls with childhood cancers.

At the moment they can have ovarian tissue frozen before treatment, which is then put back in to mature years later if the patient wants children of their own.

But if there are any abnormalities in the frozen sample then doctors will think it is too risky.

Being able to make eggs in the lab would be a safer option for those patients.

Mr Stuart Lavery, a consultant gynaecologist at Hammersmith Hospital, said: "This work represents a genuine step forward in our understanding.

"Although still in small numbers and requiring optimisation, this preliminary work offers hope for patients."

It would be legal to fertilise one of the lab-made eggs to create an embryo for research purposes in the UK.

But the team in Edinburgh do not have a licence to carry out the experiment. They are discussing whether to apply to the embryo authority for one, or collaborate with a centre that already has one.

Prof Azim Surani, the director of germline research at University of Cambridge's Gurdon Institute, said: "Molecular characterisation and chromosomal analysis is needed to show how these egg cells compare with normal eggs.

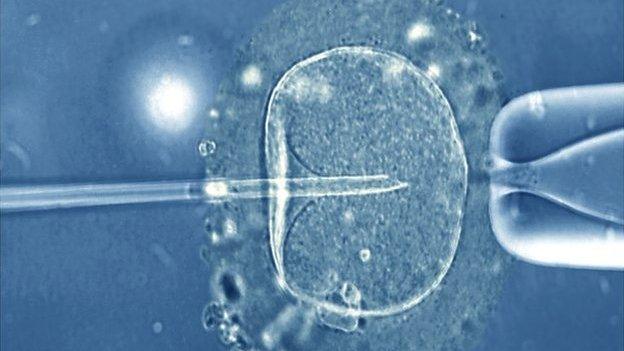

"It might be of interest to test the developmental potential of these eggs in culture to blastocyst stage, by attempting IVF."

Follow James on Twitter., external

- Published18 January 2017