DNA tests for UK’s nuclear bomb veterans

- Published

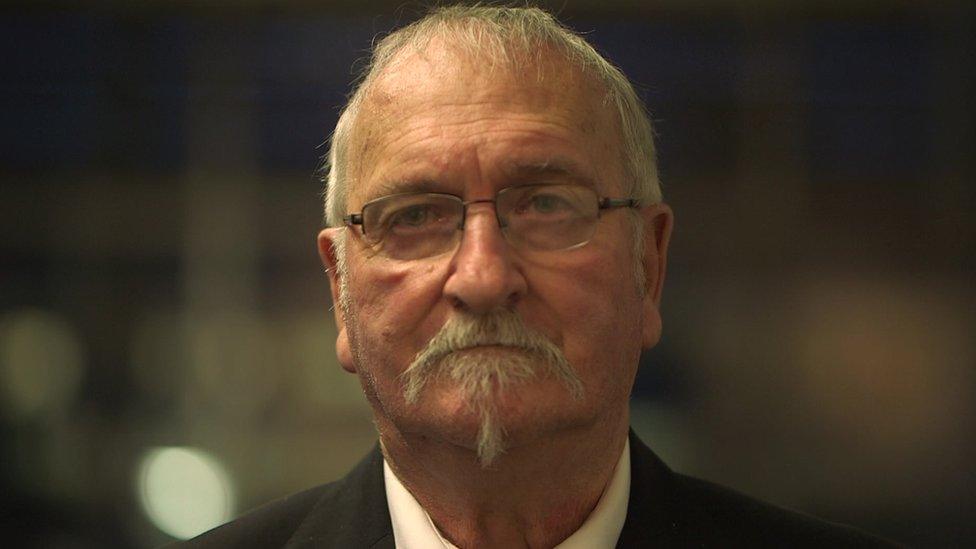

Bob Fleming was just 24 when he witnessed one of the most powerful weapons on earth

Decades ago they witnessed nuclear weapons tests in the South Pacific. Now some veterans hope new DNA testing will prove it was responsible for their subsequent ill health, which they say ruined their lives.

"It was awe-inspiring, like another sun hanging in the sky. The blast bowled people over. A few men were on the ground screaming."

Bob Fleming was wearing a T-shirt, khaki shorts and flip flops when the bomb went off.

At just 24, he had just witnessed one of the most powerful weapons on earth detonate on Christmas Island in the Pacific Ocean.

It was 1956 and the Cold War threat was growing.

The RAF serviceman was one of around 22,000 British service personnel who witnessed nuclear weapons tests on mainland Australia, the Montebello Islands off Western Australia and Christmas Island in the South Pacific between 1952 and 1958.

With their backs to the bomb, they felt the intense heat from the explosion first.

Then, after the countdown, they were ordered to turn round and look directly at the huge mushroom cloud in front of them.

"We had no protective clothing," said Bob, who's from Downham Market in Norfolk.

"We were guinea pigs. It was so bright I could see the bones in my hands with my eyes closed. It was like an X-ray."

'Genetic curse'

The veterans say the nuclear tests ruined their lives, causing cancers, fertility problems and birth defects passed down the generations.

Now 83, the great-grandfather believes that three generations of his family are living with the "genetic curse" of those explosions. Sixteen out of 21 of his descendants have had birth defects or health problems.

His youngest daughter, Susanne Ward, has thyroid problems and severe breathing difficulties, and her teeth fell out prematurely.

"It just gets worse as the next generation comes along. Our grandchildren have similar problems," Suzanne said.

"My dad blames himself, but it isn't his fault."

Tests were carried out at Christmas Island

The Fleming family now hope new DNA testing could end decades of uncertainty.

Last week, the UK's first Centre for Health Effects of Radiological and Chemical Agents was launched at Brunel University in London.

One of its projects is a three-year genetic study looking for any possible damage to the veterans' DNA caused by the tests.

Blood samples will be taken from 50 veterans who were stationed at nuclear test sites, and compared with a control group of 50 veterans who served elsewhere.

Blood will also be taken from their wives and any children they have together.

Dr Rhona Anderson, who is leading the study, said a major question to answer is whether "there is a genetic legacy of taking part at these nuclear tests".

"If no differences (in the DNA) are seen between test and control groups then this will be reassuring for the nuclear community."

'No valid evidence link'

Fewer than 3,000 nuclear veterans are still alive today.

They cannot volunteer for the study, as that might lead to bias in the results.

Veterans will be selected using military service records and information available about those who were most at risk of exposure to radiation.

The Ministry of Defence says it is grateful to Britain's nuclear test veterans for their service, but maintains there is no valid evidence to link participation in these tests to ill health.

The UK is the only nuclear power to deny special recognition and compensation to its bomb test veterans.

The veterans took their case for compensation to the highest court in the land and lost in 2012.

The Supreme Court Justices said the veterans would face great difficulty proving a link between their illnesses and the tests.

In 2015 the Aged Veterans' Fund was set up by the government using bank industry fines. It will help to fund a series of social and scientific projects.

Doug Hern was 21 when he saw five nuclear explosions on Christmas Island

Doug Hern, who's 81, and his wife Sandie, from Lincolnshire have been campaigning tirelessly for years.

When Doug was 21 he saw five nuclear explosions on Christmas Island and has suffered ill health ever since.

He said his skeleton is "crumbling". He has skin problems and bone spurs.

His daughter died, aged 13, from a cancer so rare it did not have a name. He believes this was a consequence of her inheriting his "corrupted genes".

Doug Hern's daughter died from cancer when she was 13, and he believes it was a consequence of her inheriting his "corrupted genes"

Sandie Hern is vice-chair of the British Nuclear Test Veterans' Association (BNTVA)

"The veterans have been treated abominably. They've been forgotten. We need this research to see if anything can be done to help their children," she said.

The overall aim of the new centre at Brunel is to work closely with the veteran community to improve their health and well-being in the future.

After years of personal suffering, the Flemings want to have their DNA tested and are waiting to hear if they have been selected.

Six decades on, nuclear families are still living in the aftermath of the bomb tests, and searching for answers.