Russian spy: How do you find out whether poisoning has occurred?

- Published

Public Health England has not said what the substance was

A Russian man convicted of spying for Britain and his daughter are critically ill after apparently being exposed to a mystery substance in Wiltshire.

The incident has drawn comparisons to the case of Russian dissident Alexander Litvinenko, who died in London after being poisoned by a radioactive substance.

So how will officials find out what Sergei and Yulia Skripal were exposed to and whether they were poisoned?

Specialist labs

Alastair Hay, emeritus professor of environmental toxicology at the University of Leeds, said in a case like this hospitals and other agencies would be working together to find out what happened.

Doctors will assess the pair's symptoms and carry out tests on them.

Blood tests will assess liver and kidney function, while urine may provide clues for substances excreted more rapidly, he said.

Some of these tests may be done in the hospital where they are being treated, but labs at Guy's Hospital, in London, and in Birmingham, could also be used because they are specially equipped to screen for a wide range of substances.

And there is also the government's chemical defence laboratory at Porton Down - coincidentally also in Wiltshire - which has state-of-the-art equipment to help detect trace amounts of chemicals.

But some of the tests could take several days to complete.

'Specific contact'

Prof Hay said at this stage it was too early to speculate on what the substance might be.

But he said the fact that Public Health England had said there was no wider risk to the public suggested there might have been "some very specific contact with the substance and limited spread".

Part of the investigation will look at where this contact may have taken place.

A number of city-centre locations in Salisbury have been cordoned off, including a nearby Zizzi restaurant that police said had been closed "as a precaution".

Teams in protective gear have also been hosing down the street.

Prof Hay said knowing what had been used to decontaminate the streets could give clues to what officials suspected the substance was.

An ex-radiation biologist, who wanted to remain anonymous, said it was unlikely the substance was radioactive - as in the case of Mr Litvinenko - because the symptoms developed too quickly.

Instead, a chemical source was more likely, but a biological contamination of food or the environment was also possible.

But if it was chemical this would leave a wide range of possibilities: from drugs designed for chemical warfare to artificial highs.

"We could be looking at self-inflicted accidental overdoses or a targeted attack."

A nearby Zizzi restaurant in Salisbury has been closed as a precaution

The fact police have declared the case a "major incident" also raises questions, Prof Hay said.

"Was it... because of who was affected or because of the rate of onset of symptoms?"

And the circumstances in which the pair were found could also shed light on what happened, he said.

Substance or infection?

"Ideally it would help to question someone about this, but if they have collapsed you have to test for substances.

"In the end it will be signs and symptoms and specific blood, saliva or sputum, urine, and possible faecal testing that will tell us what it was."

But could their condition have been caused by something other than a substance - perhaps a bacterial or viral infection?

Prof Hay said given the apparent speed of the symptoms, this seemed less likely. But it was still not known how the pair were feeling hours earlier.

"So a microbiology lab may well do a range of screening tests to check for a bacterial cause. But this will depend on what the clinical team feels is appropriate," he said.

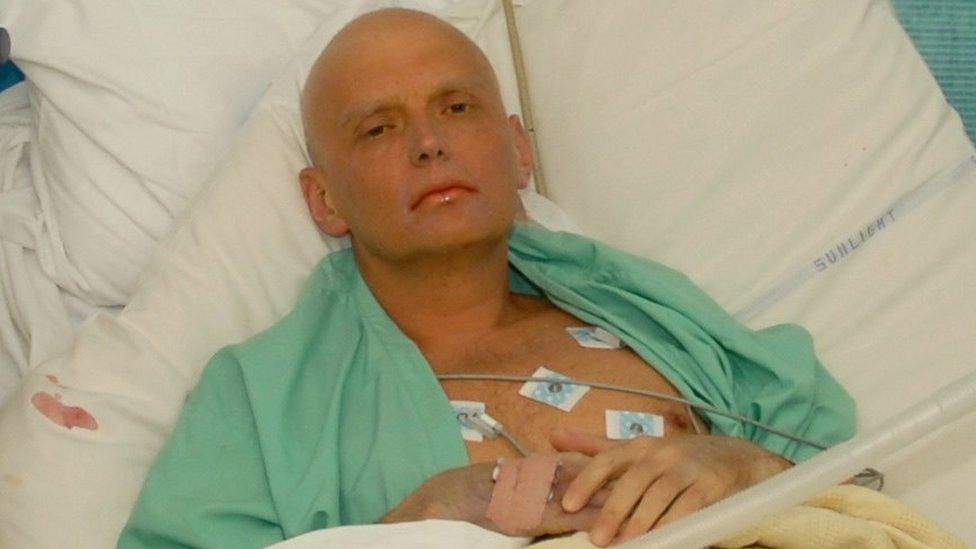

The case has drawn comparisons with the 2006 poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko

In the case of Mr Litvinenko it took weeks to establish that the cause of his death was deliberate poisoning, believed to have been administered in a cup of tea.

At first hospitals were unable to detect any radiation poisoning.

It was eventually scientists at Britain's top-secret nuclear research site at Aldermaston in Berkshire who discovered he was poisoned by polonium-210.

And it was close to a decade later that a public inquiry in 2016 concluded that his killing had probably been carried out with the approval of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Russia has said it has "no information" about what Mr Skripal and his daughter were exposed to but says it is willing to co-operate in any investigation.

UK police are not yet saying a crime has been committed.

It is likely to be a while before we know what happened and why.

- Published6 March 2018

- Published3 February 2018

- Published29 March 2018

- Published5 March 2018