Hawking: Did he change views on disability?

- Published

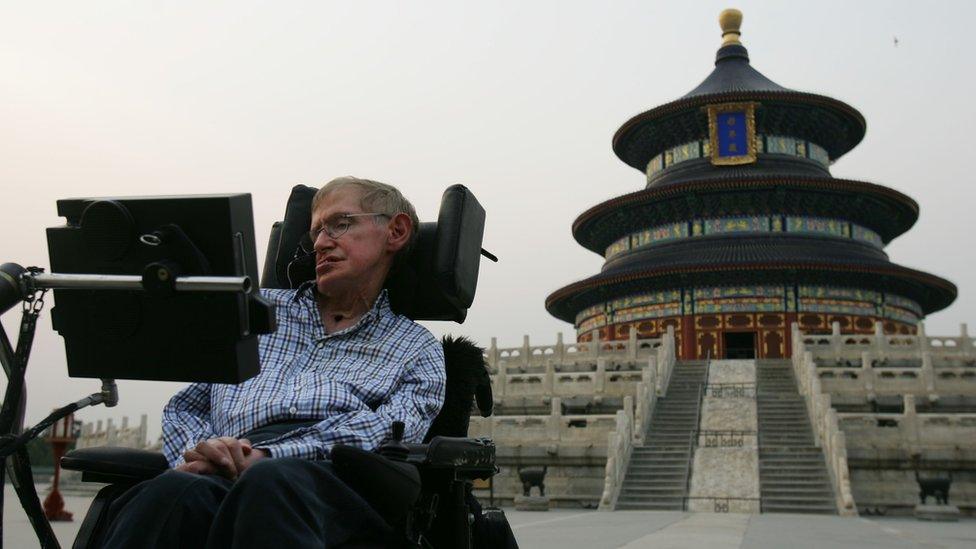

Stephen Hawking was both one of the world's most famous scientists and most famous disabled people.

His life was a juxtaposition of sparkling intellect and failing body.

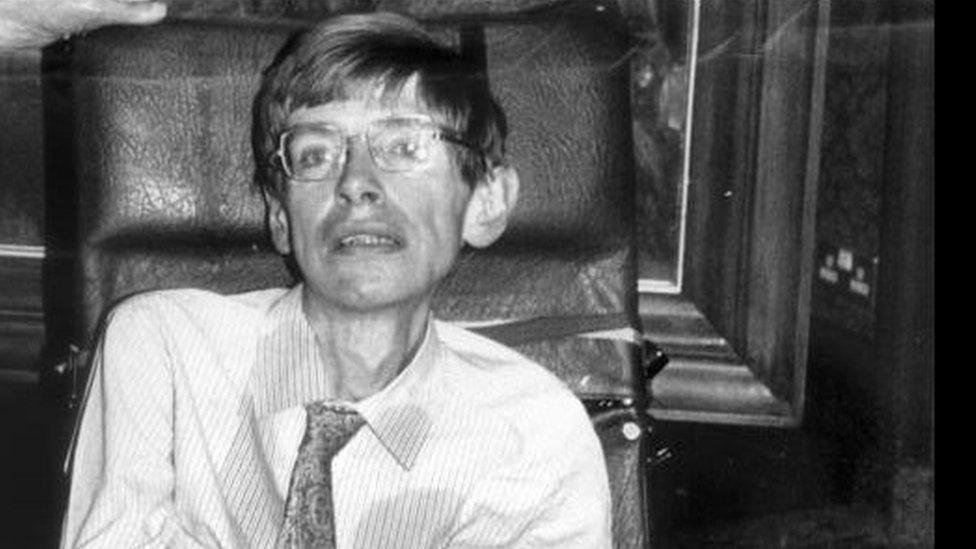

Prof Hawking was diagnosed with a rare form of motor neurone disease when he was 22.

The nerves that controlled his muscles were failing and he became trapped in his body, but his mind was still free.

He reached the height of his field while being a wheelchair user and communicating through a synthetic voice.

So did he change society's perceptions of disability?

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

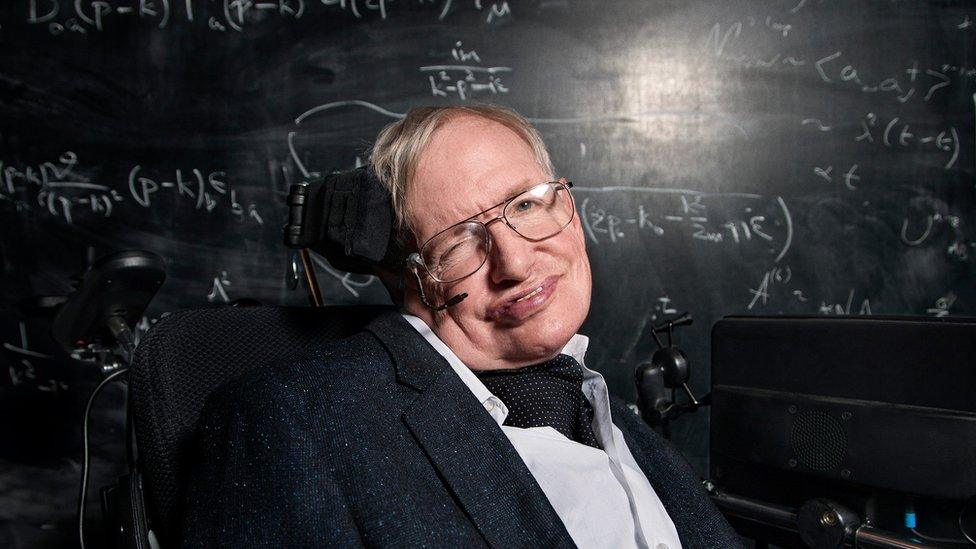

"I think he's done more than anyone else," said Prof Paul Shellard, who was a student of Prof Hawking.

He told the BBC: "He's been an incredible exemplar of there being no boundary to human endeavour.

"He identified what he could do well, exceptionally well, and focussed on that, not what he couldn't do."

That made him a role-model and inspiration for many.

Prof Hawking certainly raised awareness of motor neurone diseases.

One of his major contributions to disability in general was simply being visible - often at a time when disabled voices were missing from popular culture.

He made small-screen appearances on The Simpsons, Star Trek and The Big Bang Theory. His life was dramatised by the BBC and in the film The Theory of Everything.

Steve Bell, from the MND association, said: "He was probably the most famous person with a physical disability and it almost normalises it to see his absolute genius.

"I think it affected a lot of people, seeing he's more than a trapped body.

"The public's view of disability has changed."

But Prof Hawking's life was exceptional.

He lived five decades longer than doctors expected. Many others with motor neurone disease die in the years after diagnosis.

He was a theoretical physicist. His laboratory was in the mind, his scientific equipment was mathematics.

Prof Hawking was able to continue to pursue his career in a way that would have been much harder in other scientific disciplines and impossible in many other professions.

It remains an open question how much he would have achieved if he was disabled from birth rather than after graduating with a first at Oxford.

Today, disabled people are more than twice as likely, external to be unemployed than people without disability.

Prof Hawking's only advice on disability was to focus on what could be achieved.

"My advice to other disabled people would be, concentrate on things your disability doesn't prevent you doing well, and don't regret the things it interferes with. Don't be disabled in spirit, as well as physically," he said in an interview with the New York Times, external.

- Published14 March 2018

- Published14 March 2018

- Published28 October 2017

- Published19 August 2017

- Published2 December 2014

- Published14 March 2018