Will paying more for alcohol and sugary drinks make us healthier?

- Published

A minimum price on alcohol is being introduced in Scotland, in a bid to cut problem drinking.

It follows the introduction of a UK-wide sugar tax, as part of measures to tackle obesity.

But does making unhealthy products more expensive persuade people to make "better" choices? And what are the trade-offs associated with doing so?

Everybody will pay more

The price increases being introduced could lead to significant health improvements, but they will be felt by everybody, not only those with the unhealthiest lifestyles.

From 1 May, alcohol will not be allowed to be sold for less than 50p per unit in Scotland, which could see a four-pack of cider cost 10% more, external, while a pack of 20 cans could double in price. Wales is looking at similar measures.

The UK's tax on sugary drinks means shoppers are being asked to pay 18p or 24p more a litre, depending on just how much has been added to their drinks. The measure was introduced on 6 April.

This is happening because alcohol and sugar are associated with problems that impose a substantial cost on society.

For example, problem-drinking can lead to anti-social behaviour, crime, pressure on A&Es and increased liver disease. Excessive sugar consumption is linked to rising obesity rates, some cancers, type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

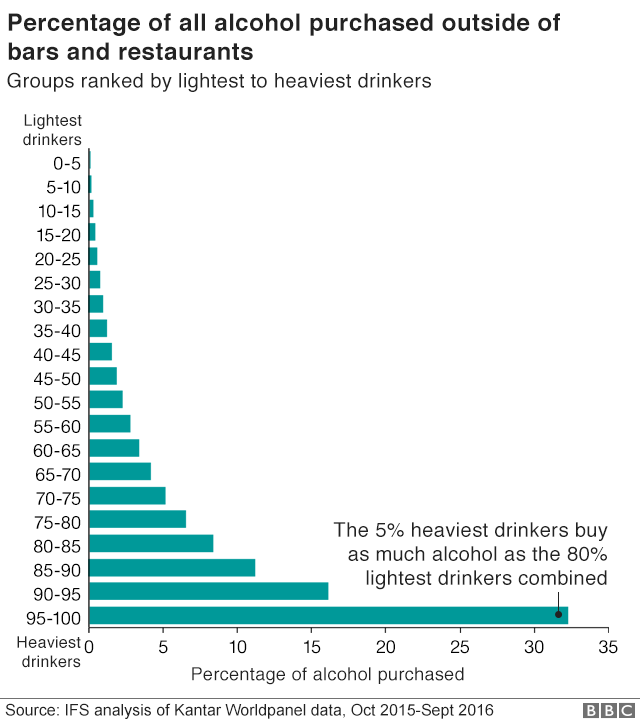

But alcohol consumption is concentrated among a relatively small number of people: 5% of households buy more than 30% of all alcohol.

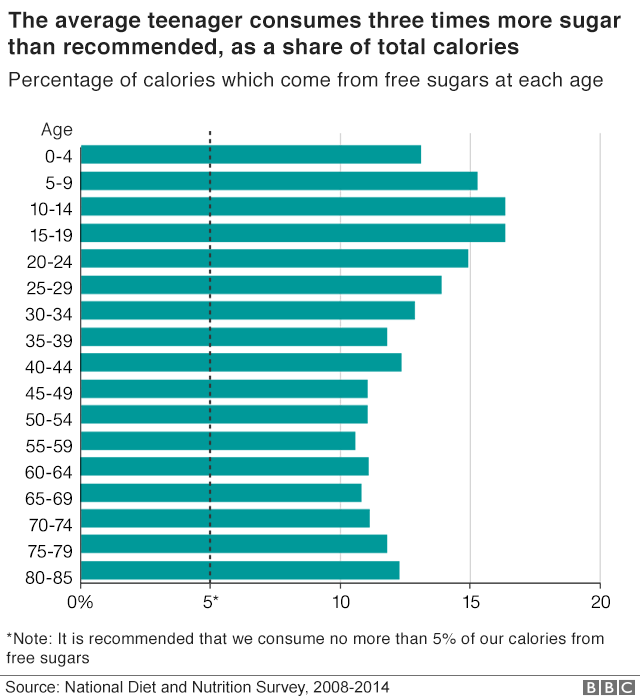

And the government is particularly concerned about obesity among children and young people: teenagers consume more than three times the recommended amount of free sugars - those which are not naturally present in food.

The government has to consider the trade-off between potentially large improvements to public health and making everybody pay more.

Will shoppers make healthier choices?

Price increases will be most effective if the people who consume too much sugar and alcohol significantly reduce their intake.

But people respond differently to higher prices, depending on how much they like the product. And, in the case of alcohol, addiction can also be a factor.

Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggests that heavy drinkers respond less strongly to price increases.

For example, if the price of alcohol increases by 1%, the percentage fall in consumption among households which buy more than 40 units per adult each week is only half as large as among those which buy fewer than eight units, external.

What people choose to buy instead also matters.

In the case of sugary drinks, increasing the price of a bottle of cola might work if people choose water instead.

But only some drinks, and no foods are being taxed. So, if people choose to buy a milkshake, a chocolate bar, a cake, or ice cream instead of the cola, then the impact of the tax on sugar consumption will be reduced.

It can also be difficult to know how great the impact of a price rise has been, compared with other measures.

The proportion of adults smoking halved between 1974 and 2013, external - at the same time as the real rate of excise duties on tobacco more than doubled.

But higher taxes are not the only thing that affected behaviour, as awareness about the dangers of smoking also increased significantly.

More stories like this:

What will shops and manufacturers do?

The food and drink industry will react to the taxes - but not necessarily in the intended way.

In the case of sugary drinks, manufacturers can choose to change prices by more or less than the tax, which will affect how much consumption falls.

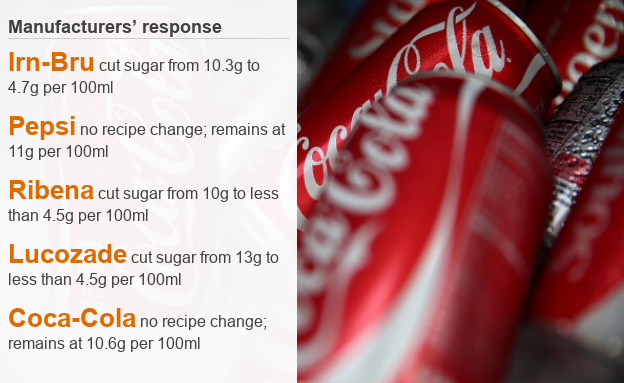

They may also change their products - a move which could make the policy more effective.

There are examples of this happening - several soft drinks companies have already reduced the sugar content of their products to avoid the tax. The sugar content of Fanta has been reduced by 30%, for example.

If people are happy to buy the reduced sugar varieties, this could be a relatively effective way of reducing the nation's sugar intake.

And new recipes can work - voluntary targets led to a 5% reduction in the salt, external content of groceries between 2005 and 2011.

Money from the sugar tax will go to the government, which could use some of the tax revenue it receives to improve public health, for example by increasing funding for school sports.

However, minimum pricing per unit of alcohol is likely to create windfall profits for the manufacturers and retailers.

If the alcohol industry uses the money to increase promotions, or advertising, this could undo some of the potential benefits of the policy.

The sugar tax and minimum pricing

The UK-wide sugar tax took effect on 6 April

18p per litre if the drink has 5g of sugar or more per 100ml

24p per litre if the drink has 8g of sugar or more per 100ml

A sugary drink is exempt if it contains at least 75% milk

The Scottish Alcohol Minimum Pricing Bill takes effect 1 May

Minimum pricing for alcohol to be fixed at 50p a unit in Scotland

Other ways of suggesting healthier choices

Introducing taxes is only one of many options available to the government.

A lot of attention has been paid to differences in the quality of diet between different people. But there are also big differences in the same person over time.

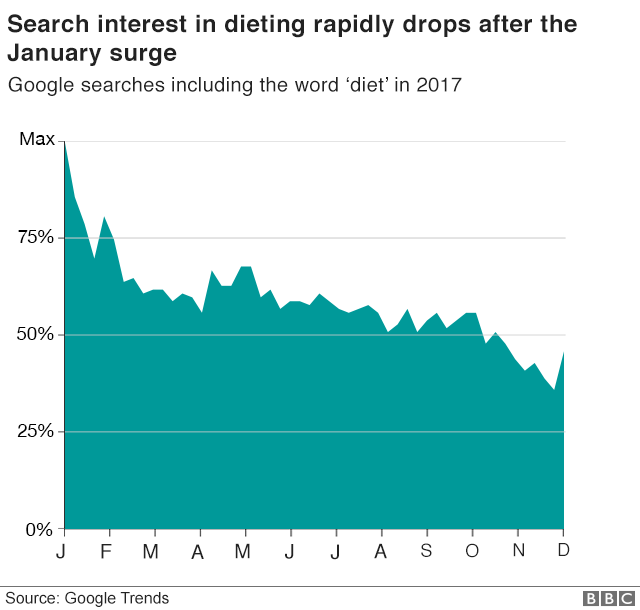

Research by the IFS suggests that the share of calories people get from healthy food increases sharply in January and falls by 15% by the end of the year, external. Similarly, searches for "diet" on Google spike at the start of the year.

This suggests that if the government could persuade people to behave as they do in January for the whole year, then there could be substantial improvements in nutrition.

And "nudge" policies that encourage people to make better decisions - such as not allowing sweets and chocolates to be sold next to tills - could be used more widely.

Such policies could be effective at reducing impulse buys that people later regret.

A related idea would be adding information about the dangers of excess sugar and alcohol to food labelling, just as health warnings are placed on cigarette packets.

No easy solution

The challenges posed by obesity, poor nutrition and alcohol consumption are substantial.

All the options involve trade-offs.

The government needs to balance the potential improvements to public health against the costs to consumers.

It is likely that a whole range of policies will be needed to tackle these major public health challenges.

Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Kate Smith is a senior research economist, external at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, an independent research institute which aims to inform public debate on economics.

Charts produced by Daniel Dunford

Edited by Duncan Walker